An ethnic Pole born in Ukraine in the Russian Empire, who became one of the most celebrated Soviet artists, Kazimir Malevich used art to give voice to the multiple legacies he had inherited. Malevich’s biography and his overlapping identities are, perhaps, best reflected in his artwork. While most critics and admirers think of the notorious Suprematist Black Square when referring to Malevich, they sometimes omit the long and meandering path that Malevich’s creativity took to reach that supremacist destination. Kazimir Malevich shifted styles and sought new ways of painting, while experimenting with forms and substances.

Kazimir Malevich: An Artist With Many Faces And Identities

During his life as the face of the Russian avant-garde, Kazimir Malevich tried many painting styles: Neo-Primitivism, Symbolism, Impressionism, Futurism, and Cubism, to name a few. Yet, none of these styles truly reflected the painter’s view of reality. Thus, he invented his own movement – Suprematism. Malevich not only applied the principles of Suprematism to his painting but transplanted it to other fields of art, including architecture, cinematography, and design.

Brought up in the Ukrainian countryside, Kazimierz Malewicz spent most of his early childhood in villages. During his youth, he absorbed the overlapping folk traditions of the area where Orthodoxy blended with Catholicism and Slavic languages intermingled. Thus, it was unsurprising that folklore influenced Malevich’s path in art.

However, it was not until the family moved to Kursk that Malevich realized his lack of formal art education. Wishing to pursue a career in painting, the young artist knew he had to move to either Moscow or St. Petersburg. Later, Malevich would write that because famous painters and opportunities were in Moscow. Thus, it was there that his path led.

Kazimir Malevich tried entering the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture three times – all without result. Before becoming one of the most popular and influential painters of the twentieth century, the future founder of Suprematism was considered hopeless and talentless by the professors of this prestigious institution.

In the face of this rejection, Malevich slowly turned into his own unique master, whose artwork was far more varied than almost anything created by his peers. The following pieces of art demonstrate the ingenuity of the twentieth century’s most versatile painter and the many facets of his works. After all, Malevich and his art are much more than complicated geometry and avant-gardism.

1. Triumph Of Heaven, 1907

The Triumph of Heaven is an early example of Malevich’s work that reflects the beginning of his unique manner of painting and the artistic trends in the Russian Empire. This epoque saw decadence and symbolism taking over the cultural life in both Moscow and St. Petersburg. In 1907, Malevich visited an exhibition of the Blue Rose Symbolist group. The event inspired the young painter to such an extent that he produced a series of paintings deeply steeped in religious mysticism. The Triumph of Heaven became one of Malevich’s most famous early works as well as one of the most iconic pieces of Russian Symbolism.

The Triumph of Heaven is a sketch for a fresco that blends folk traditions and Orthodox mysticism. Surrounded by a golden glow, peaceful heavenly residents dwell in a green meadow, while rows of figures with limbs rise above them only to be covered by another omnipotent being.

Malevich’s exploration of religious themes was influenced by his own Catholic-Orthodox upbringing and his interest in both Eastern philosophies and the peasant art and folklore of Eastern Europe. “Through icon painting, I managed to understand the emotional art of peasantry…that I have always loved,” Malevich wrote once. In his Symbolist paintings, he tried to appreciate both high and popular culture, blending them together.

2. Landscape With A Yellow House, 1906

Malevich’s fascination with popular culture and his simplified representation of forms together ignited his desire for experimentation. His Landscape with a Yellow House is an example of the artist’s interest in Impressionism. In 1908, the art journal Golden Fleece hosted an exhibition that brought Matisse, Gaugin, and Van Gogh’s works to Moscow. Intrigued by these new art styles, Malevich saw their Impressionist roots. Because of this, he chose to delve into the unclear and bright haze of colors that characterized one of the world’s most notable trends in painting.

Impressionism was not simply a phase in Malevich’s life but a recurring leitmotif. His Landscape was one of his first attempts to create a colorful mosaic of points that highlighted the scene’s ambiance rather than the precise shapes of objects.

Later, during his personal exhibition held in 1928, the famous painter revisited Impressionism. This time, Kazimir Malevich referenced and reframed Degas, Monet, and Cezanne’s paintings, all of whom he admired. It is not by chance that Kazimir Malevich counted the beginning of his personal artistic path from the first Impressionist sketches that he painted in Kursk.

3. Woman At The Tram Stop, 1913

Cubo-futurism occupied a special place in Malevich’s creative path. Venturing into avant-garde styles, the painter was drawn to simple geometry. What started with geometric depictions of peasants ended with a total deconstruction of shapes that can be seen in Woman at the Tram Stop. The painting was created when young Malevich could barely afford canvases. Although poor and barely surviving, he still actively promoted the emerging Russian avant-garde.

Woman at the Tram Stop was one of the 15 paintings that Malevich prepared for the first exhibition of the Russian Futurists. The picture is a puzzle that combines seemingly incompatible objects. Stairs, architectural vignettes, a calendar – everything appears on a canvas where these pieces of life tell no coherent story but rather suggest that the spectator must come up with one.

There is actually no silhouette of a woman in the painting. Instead, multiple warped shapes remind one of a tram station, a calendar indicates the passing of time, and, perhaps, parts of the road lead to some unknown destination.

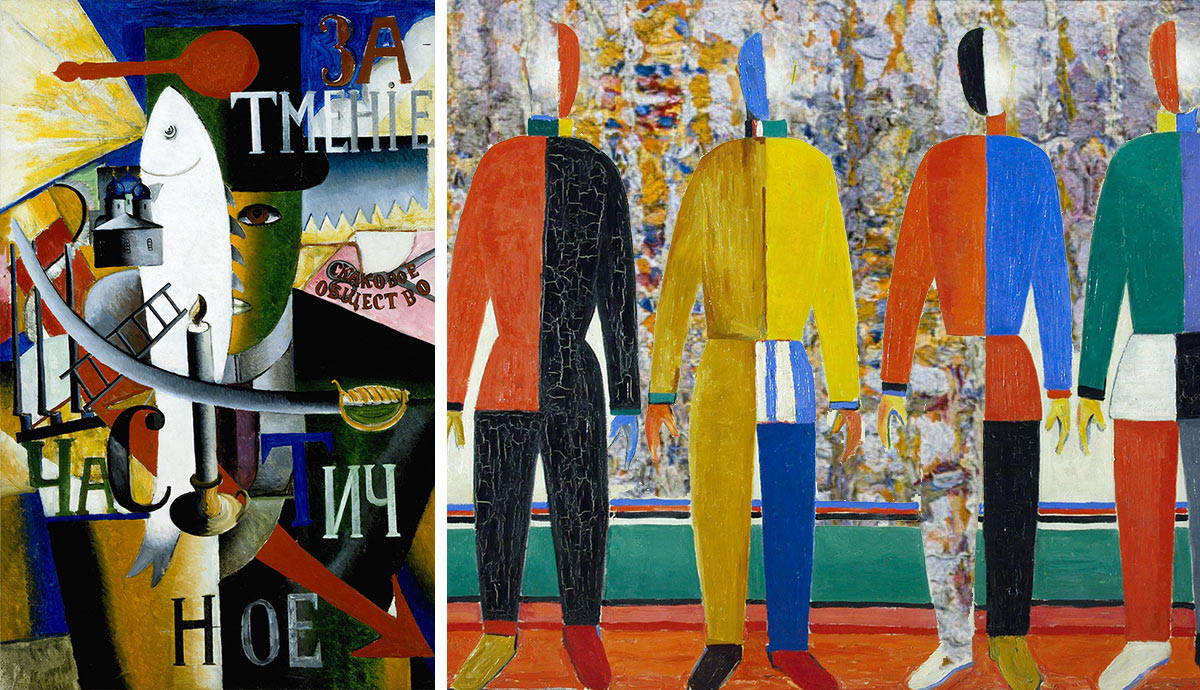

4. An Englishman In Moscow, 1914

One of Malevich’s most enigmatic works alongside Woman at the Tram Stop, An Englishman in Moscow binds together abstract geometry, vibrant colors, and touches of realism. A green-faced man is juxtaposed against a fish, a spoon, an Orthodox church, and calligraphic signs in Cyrillic. One of them reads “Equestrian society,” while the other combination of letters forms mysterious words “Eclipse” and “Partial.” The busy scene leaves another puzzle for spectators to solve, hinting at the connection between seemingly random objects. Futurist in its nature, the painting is also a joke that breaks away from tradition. After all, it may seem strange and even revolting to certain viewers, but never boring or familiar.

5. Supremus 56, 1915

Kazimir Malevich laid the foundation of Suprematism in 1915 when he published his manifesto titled “From Cubism to Suprematism.” In his work, the painter proclaimed the creation of a path that would lead to a new realism. The new realism envisaged by Malevich meant an objectless depiction of reality free from all constraints. Above all else, Suprematism emphasized color and shape. It was Malevich’s firm belief that a master did not have to copy nature but rather create new worlds of his own. One such world was his Supremus 56.

The picture is one of the typical Suprematist paintings created by Malevich. As such, it hides several secrets. First, it was sketched with a freehand pencil, leaving the underdrawings partially visible. Second, the clear edges were achieved due to the painter’s reliance on a cupboard to guide his brush. Once lifted, the cupboard left a characteristic ridge that remains there today, branding the painting as a window into a unique world made by a unique man.

6. The Black Square, 1915

Among all of Malevich’s paintings, there is one of which almost everyone has heard. It appears in numerous reproductions. It sparks debates and ignites controversies. The notorious Black Square is no longer a painting but a social phenomenon.

For a conservation expert, the tale of the Black square begins with the painter’s impatience. Malevich painted on the surface of his wet canvas, not waiting for it to dry. As a result, the so-called craquelures, dye cracks, appeared in the pitch-blackness of the figure due to Malevich’s haste. The artist was known for his negligence which later turned many of his Suprematist paintings into cracked pieces of art. The Black Square is one such capricious work.

A black square placed against the sun appeared for the first time in the 1913 scenic designs for the Futurist opera Victory over the Sun. Then, two other black squares followed, each of them symbolically ending realistic art. In a way, Malevich’s Black Squares were all supposed to announce a new beginning and bring the previous centuries of artistic expression to a close. Bridging the gap between Futurism and Constructivism, the Square was a “zero point of painting,” a reflection of all that is revolutionary and new. It was a precursor to the political order that came after 1917 and a statement from a painter who lived to see the fall of the Russian Empire and the rise of the Soviet Union.

7. Suprematist Composition: White On White, 1918

How many shades of white can an eye discern? That was one of the questions that Malevich attempted to answer with his White on White – another Suprematist painting that many associate with the artist today.

Created in the year following the October Revolution of 1917, this piece of art is provocative and ground-breaking. A monochrome square appears on a white canvas, conveying a sense of color, depths, and volume. A Constructivist critic who saw the painting during an exhibition allegedly stated that it was “an absolutely pure, white canvas with a very good prime coating. Something could be done on it.”

8. Sportsmen, 1931

In 1930, Malevich was arrested and spent three months in prison on trumped-up charges of anti-Soviet propaganda. The new regime slowly turned away from his unrestrained art, endangering the artist’s freedom. After his release, Malevich returned to painting peasants and workers, calling his new endeavors an attempt to express Suprematism in the form of human figures. The simplicity and folk art that inspired Malevich throughout his life found an outlet in his primitivist depiction of those who surrounded him. Thus, his Sportsmen became one of his most iconic Suprematist paintings.

While Suprematism signified the emancipation of the artist and his figures that broke away from constraints, the Sportsmen demonstrated a triumph of creativity and insubordination to its fullest. The painting only shows energy and dynamics and ignores space, time, reality, and several other rules. Malevich wrote that his last Suprematist paintings were born of despair. Among them, the protest of the Sportsmen is as palpable as the alienation of the Peasants.

9. Peasants, 1930

The Peasants is another of Malevich’s famous works that marks his reassessment of Suprematism. Two figures in yellow and orange stand against an intricate brocade of colorful fields as Stalinist repressions take over the country. Both peasants are faceless, their expressions replaced by shadowy white masks. Ingenious as always, the Neo-Suprematist artist reflected the faceless dread that Kazimir Malevich himself felt towards the growing oppression in the Soviet Union.

This piece was one of Malevich’s last explorations of Suprematism. Following his arrest and being aware of the stiffening censorship, Malevich started combining Suprematism and Neoclassicism in his works while still preserving his fascination with folk culture.

10. Woman Worker, 1933

In 1933, Malevich painted a “Neoclassical” portrait of a female worker. This piece still confuses critics, who cannot decide what the position of the woman’s hands signifies. From one point of view, the worker holds her arms in a way that suggests the familiar position of the Madonna’s hands. While the child Jesus is missing, the expression of the woman’s face is dazed and straight, her cheeks flushed and her face pale. The worker is brightly dressed, her fingers are calloused, and her gestures and pose remind one of familiar Christian iconography.

Adjusting to the new circumstances, Malevich no longer addressed the religious topics that fascinated him in his youth. Instead, he opted for a fusion of traditions and messages, creating portraits that reflected the new style of Socialist Realism as well as the ruptures that appeared following the shifts in politics and art. In the corner of the painting, one can still discern the painter’s signature – a black square, the very same notorious form that became Malevich’s namesake and brought him worldwide fame.

11. Self-portrait, Kazimir Malevich, 1933

In the thirties, Malevich rediscovered Renaissance art, infusing it with the legacy of Byzantine icon painting and his own Suprematist tradition. In one of his last works, Malevich depicts himself as a proud Venetian Doge, looking into the distance. The Neo-Realistic portrait represents the artist as a patriarch who remains loyal to his Suprematist past, leaving a small black square in the corner as his signature. An old-fashioned robe goes against the avant-garde black square and the nature of new Soviet tastes that dominated Russia’s cultural scene.

Two years after Malevich finished his Renaissance-style self-portrait, he painted another one that was reminiscent of Velazquez’s later paintings. That same year, Malevich died in Leningrad, leaving behind one of the most varied legacies any artist could have ever produced. The abundance of styles he addressed and the ingenuity of his technique proves the unique versatility of Kazimir Malevich. His multifaceted art mirrored his multifaceted identity and the ever-present fascination with Eastern European folklore, as well as the legacies that surrounded him during his life.