Since our earliest times, humans have been storytellers, and there doesn’t seem to be a topic any more interesting than ourselves. The autobiography is always a great resource to those looking to delve into the intricacies of history. But Americans, displaying their “melting pot” of diversity, might be said to have perfected the autobiography.

From colonial times to expanding the frontier, from tales of injustice to those of exploration, a slew of American autobiographies address the big picture of development in the US by looking at it in microcosm. Through autobiographies like these, we glimpse some major turning points in our past from very specific angles – the perspectives of the authors.

1. Benjamin Franklin: Secret Writer Turned Scientist

“If you would not be forgotten as soon as you are dead and rotten,” wrote Benjamin Franklin, “either write things worth reading, or do things worth writing.” The witty axiom, one of many included in Poor Richard’s Almanack, best sums up the goal of an autobiography. It is written because the author, in his opinion, has done things worth writing and writes them down because he feels they are worth reading.

Born in Boston in 1706, Franklin was one of 17 children. Their father made a living making soap and fashioning candles. Amid the booming family, Ben tried to find his place. Before he had hit his teen years, he was apprenticed to his brother James and thrust into the printing profession. Meanwhile, he indulged his insatiable appetite for reading – to make up for his lack of schooling. He aspired to be a writer himself someday.

In 1721, his brother James established the New-England Courant, a newspaper open to submissions from readers. Ben wanted to try his luck and see if he might get published. To avoid the suspicion and scrutiny of his brother, he submitted essays under the pseudonym “Silence Dogood,” an innocent middle-aged widow. The ruse worked, and 14 letters from Mrs. Dogood appeared in the Courant. In his Autobiography, Franklin notes that his ability to write well was a great help to him throughout his life. Later, he debuted his own printing business, and several years afterward, he was writing and printing Poor Richard’s Almanack, again under a pen name. Those writing skills came to his aid in drafting the Declaration of Independence.

A life-long seeker of knowledge, Ben believed that all discoveries could become useful. In 1743, he founded the American Philosophical Society, an organization devoted to a wide array of sciences. (Members included George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson.) Today, his own scientific pursuits in areas such as electricity and optics are legendary. He was even an amateur paleontologist. The Autobiography, published posthumously, appeared in many different editions and languages. It has been praised as the embodiment of the American dream.

2. Thomas Jefferson: Controversial Political Shaker

After George Washington, few American revolutionaries are as renowned as Thomas Jefferson. Like Franklin, he was born in colonial America, had a hand in drafting the Declaration, and is counted among the Founding Fathers. He served as the third President, oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, and employed Lewis and Clark to reconnoiter the new territory. Jefferson’s ideals have influenced philosophies across the political aisle in the US and abroad.

While perhaps not so controversial in his own day, Jefferson was known for several traits that clash with modern common sense. In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781-1782), he clearly expressed a hierarchy of races – with Blacks typically falling to the lowest category. He perceived Black people as sweaty, stinky, passionate, and uncreative. He even called their skin an “eternal monotony,” incapable of expressing a range of emotions like white men’s skin. Needless to say, his ideals of liberty were not often geared toward enslaved people. Amid this seeming hypocrisy, he is a hero for some and a fiend to others.

An amateur scientist and model architect, Jefferson was well-read with a reputation as an avid book collector. During the War of 1812, the British burned the extant Library of Congress. Jefferson contacted Samuel H. Smith, editor of the National Intelligencer, asking him to act as a go-between for offering his book collection to Congress. Jefferson offered thousands of books, and Congress recorded the addition of 6,487 of his volumes to their damaged library, paying Jefferson the handsome sum of $23,950 in return. The modern Library of Congress honors his memory with the Jefferson Building.

“I cannot live without books,” Jefferson once remarked. So it seems natural that he would wind up writing one about himself. In his old age, he began his autobiography, which explores his youth, the era of his life where he helped write the Declaration, and his relations and opinions of the French.

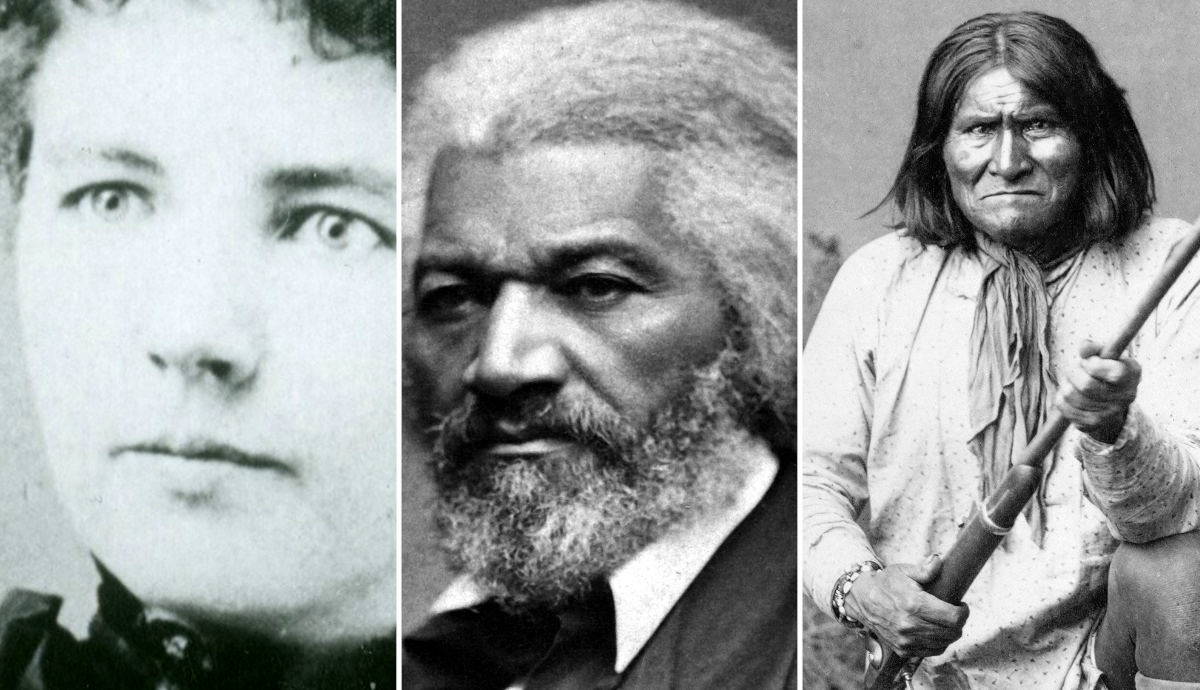

3. Geronimo: Criminal and Hero Wrapped into One

When we think of patriots, we tend to think of the revolutionary founders and fighters dotting the pages of early American history. But the colonial civilians weren’t the only ones who defended their homeland in the New World. The Native Americans, since they began to encounter the white man, have often fought for the land they saw as their own, the country they had lived in for generations. For Geronimo, a 19th-century Apache leader and war chief, this was his fight too.

“I was born in No-doyohn Canon, Arizona, June 1829,” states Geronimo in his autobiography. He was the fourth in a family of eight children. The Chiricahua Apaches were known for defending their homeland, their war parties often traveling through Arizona and parts of Mexico (Arizona would not become a state until 1912). The Chiricahua were on strenuous terms with the Mexicans. When one group offered peace, the other was usually about to doublecross them.

In the summer of 1858, Geronimo and his tribe, the Bedonkohe Apaches, passed through Sonora, Mexico heading for Casa Grande. On the way, they halted and camped outside a city, trading with the townspeople for several days. One afternoon, Geronimo recalled, members of their tribe rejoined the Apache men and told them that Mexicans had attacked the camp in their absence. The survivors bemoaned the loss of many women and children. When Geronimo himself returned to the ravished encampment, he tells us: “I found that my aged mother, my young wife, and my three small children were among the slain.”

After that, Geronimo harbored a distaste for Mexican people. He spearheaded a party of warriors that enacted raids or revenge on the Mexicans. From his encounters with his Spanish-speaking enemies, the Apache war chief came to have a decent grasp of Spanish. In the coming decades, his battling efforts were turned toward liberating other Apaches who had been moved to a reservation in Arizona. He led them in attacks on white settlements in the area. In the 1880s, Geronimo surrendered to the US military on three occasions, subsequently escaping after two of them. He surrendered for the final time in 1886 but was not allowed to go to Arizona.

After two decades as a prisoner of war, Geronimo’s story piqued the interest of S.M. Barrett, who, with the permission of President Teddy Roosevelt, proceeded to interview the old Apache. Geronimo orated the text of what became his autobiography through the assistance of an interpreter, Asa Daklugie, a second cousin of Geronimo. The work sheds light not only on his personal life but on Apache traditions and an important period during America’s westward expansion. His autobiography launched Geronimo into a new-found legend, a prisoner of war hailed as a hero.

4. Frederick Douglass and the Pathway to Freedom

The power of written media can be highly influential. Born enslaved in 1818, Frederick Douglass acquired a love of reading at an early age. When he was 12, The Columbian Orator, a collection of essays on politics, rights, and natural law, began to impact his thinking and, eventually, how he would attack pro-slavery perspectives. The Columbian Orator gave the young Douglass a thirst for the truth and the wisdom to defend it.

Douglass was a headstrong man who did not take kindly to the “crouching servility” in which so many enslaved people found themselves. He had good reasons to loathe his position – as many who were enslaved did. It was not uncommon for families of Black enslaved people to be separated, sold or resold, and sent to different plantations. Frederick came from one such broken family. His mother worked at a different plantation than himself, and he never learned who his father was.

In his first autobiography, he recalled the murder of numerous enslaved people at the hands of their self-designated superiors. The boy’s owner scoffed at the idea that Frederick might learn how to read. “If you teach that n****r how to read,” the master said, “there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.” Regardless of how bigoted the man’s words were, the youth recognized in them a certain reality. Douglass discovered the “pathway from slavery to freedom” and recognized literacy as a crucial stepping stone. For him, literacy became a vehicle to deliver his life’s greatest labor, the message of freedom, equality, and justice.

With some help, Douglass escaped at age 20. He started a family, joined the abolitionist movement, and became a well-known orator. His first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845), was met with acclaim. A second autobiography – My Bondage and My Freedom – followed a decade after and built upon the contents of the first. During his writing career, he edited several newspapers, including Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Douglass’ Monthly, New National Era, and North Star. Throughout his life, Douglass desired to defend the rights of “my brethren.” In the post-Civil War era, he favored the women’s suffrage movement and opposed segregation.

5. Harriet Jacobs: A Story of Abuse

In the mid-1800s, a number of autobiographical and creative literary books were published, elucidating the living conditions of African American enslaved people. Frederick Douglass’s Narrative was a big one, as was the famous work of historical fiction Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Another renowned abolitionist text released around this time, just before the Civil War, was Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).

The author, billed as one Linda Brent, was later discovered to be Harriet Ann Jacobs, an escaped enslaved woman who used the pseudonym for protection. Unlike Uncle Tom, the contents of Jacobs’ Incidents were far from fictional. Just like broken enslaved families, sexual relations between enslavers and the enslaved were not uncommon. (Reports since the 1800s claim that Thomas Jefferson had relations with his enslaved maid Sally Hemings, for example.) Whether such relations were consensual or not is another matter. But in the case of Harriet Jacobs, they were not.

After abuse and unwanted advances from her master, Jacobs started a relationship with another white man, becoming pregnant at 16. At 22, she was on the run for her freedom. After years of hiding with freed family members, she would eventually publish Incidents. Amid the Civil War, Harriet and her daughter Louisa went back to the South, assisting African Americans in need in the Union territories.

6. Mark Twain: A Real Adventurer with a Fake Name

Few classic American novelists are as well-known as Mark Twain, author of popular boy adventure tales like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and of dashing, clashing warrior stories like A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and Joan of Arc. Predominantly recognized by his writing pseudonym, the real-life Samuel L. Clemens not only wrote about adventures – he lived them.

Many great American writers have found themselves drawn to life on the water: Jack London, E.B. White, Ernest Hemingway, and Clemens himself. Mark Twain had a long-running relationship with the Mississippi River. Twain often wrote about his travels, such as in Roughing It (1872), where he discusses his visiting Hawaii, and The Innocents Abroad (1869), where he tells of his adventures through Europe, Africa, and the Holy Land. However, his most revered autobiographical text remains Life on the Mississippi (1883), which details river-oriented adventures in a pre-Civil War United States.

In his early twenties, Twain received his steamboat pilot’s license. Besides being a Mississippi riverboat pilot, the young Twain occasionally worked as a journalist or travel writer. Later, he joined a Confederate militia, serving only a brief stint before deserting. Soon, however, he was back to reporting. In the following decades, he turned to writing popular fiction, and his most classic stories – those of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn – were inspired by the setting of the Mississippi River.

7. Ulysses S. Grant and the Last Battle

Born in 1822, Ulysses S. Grant was a well-trained soldier by the time the Civil War broke out in 1861. Educated at West Point, Grant displayed outstanding heroics during the Mexican-American War, a struggle he later deemed a “wicked war.” Nevertheless, he was a hardened veteran by the onset of the Civil War, when he proactively began training troops. This made him a prime pick to move up through the ranks.

Grant was brigadier general before the year was out. He continued to distinguish himself throughout the war until President Abraham Lincoln called upon him to lead the Union armies in offensive campaigns against the Confederates. Under “Unconditional Surrender” Grant, Confederate General Robert E. Lee called it quits in Virginia.

The coming years brought two presidential terms to Grant. The commander of the Union armies became the Commander-in-Chief. However, his personal vices lingered and hovered over him: his excessive drinking and habit of smoking cigars, the latter causing him problems later in life. Out of monetary need, the former president decided to write his war memoirs. Century magazine was interested in Grant writing a series of articles on his experiences, and the idea for a book-length work soon followed. Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain), a friend of Grant’s, wanted to publish it, and the Commander conceded. But there was one last battle that Grant faced…

A doctor discovered cancerous ulcers in Grant’s throat. Twain visited him and remarked that his smoking had likely contributed to the development. Short on time and in need of money, Grant poured a surplus of energy into successfully finishing his memoirs. He died in 1885, two decades after the end of the Civil War. The work was originally published in two volumes under the title Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant.

8. Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Story of Rejection and Success

Laura Ingalls was born in 1867 near Pepin, Wisconsin. For the next decade or so, the family moved repeatedly – from Kansas to Wisconsin to Minnesota to Iowa and beyond. Laura became a school teacher and eventually married Almanzo Wilder. She branched off from teaching and did some writing, finding work as a columnist addressing poultry-raising and other farming topics. Her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, also broke into the publishing industry.

Rose and her mother wrote back and forth, fleshing out the idea for a series of books that would present a historical fiction narrative about the Ingalls family and their survival. The success of Laura’s first novel, Little House in the Big Woods (1932), secured the future of the eight-volume series. The Little House books are what Laura Ingalls Wilder is best known for. But many people don’t realize Ingalls previously penned and proposed a non-fiction autobiography that several publishers rejected. It was called Pioneer Girl. These memoirs finally received their due attention when, in 2014, they were posthumously released in Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography.

The historical fiction that Laura Ingalls Wilder gave us remains better known than her true autobiography. Her children’s books became the basis for the popular American TV series Little House on the Prairie. Furthermore, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for juvenile literature is named in her honor, of which she was the first recipient.

Further Reading:

Calkins, C.C., Ed. (1975). Reader’s Digest the story of America. The Reader’s Digest Association.

Douglass, F. & Jacobs, H. (2004). Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave & Incidents in the life of a slave girl. The Modern Library.

Franklin, B. (2011). Advice from Poor Richard’s Almanac. In J. Avlon, J. Angelo, & E. Louis (Eds.), Deadline Artists (pp. 371-374). The Overlook Press.

Geronimo (1970). Geronimo: his own story (S.M. Barrett, Ed.). Ballantine Books, Inc.