We often think of ancient Greece as the cradle of civilization, the place and time where many of the institutions and inventions that we have today were created. In this article, we will go further back in time, in order to explore the many ways in which ancient Egypt influenced Greek art, religion, philosophy, mythology, and society in general.

1. Religion: The Similar Cosmogonies of Egypt and Greece

To measure the extent to which ancient Egypt influenced Greece, we should start at the beginning. When comparing the cosmogonies (that is, the myths that explain the origin of the world and everything in it) of both civilizations, one cannot help but notice more than a few coincidences. Of course, both the Greeks and the Egyptians developed different accounts of the creation of the world throughout their millennia-long history — but the similarities are striking when you look at the main ones.

To begin with, the primordial gods and goddesses — Gaia, Tartarus, and Eros in Hesiod’s Theogony, and Atum according to Egypt’s Hermopolitan Cosmogony — were all spontaneously born from Chaos. The rest of the gods are the descendants of these early deities. This means that both the Egyptian and Greek gods are part of two big families.

Furthermore, in both cosmogonies, the first gods and goddesses represented forces of nature. Gaia is a manifestation of the Earth, Tartarus is the Abyss, and Erebus, the Darkness. In Egypt, the primordial god, Atum, spawned Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), who in turn became consorts and had two children of their own: Geb (land) and Nut (sky).

Not only are the gods in both mythologies related to each other, but their reproduction seemed to be similar to that of normal human beings, a feature that is not common in other world mythologies and that the Greeks no doubt learned from Egyptian religion.

2. History: Early Visitors from Ancient Greece

Not only was Herodotus the first person to write an account of the past that we can call “historical,” he was also one of the most read authors in antiquity. He visited Egypt in the middle of the 5th century BCE when Egypt was under the rule of Persian kings, Greece’s long-time enemies. There, he saw for himself many of the customs he later described in his celebrated Histories, but perhaps more importantly, he systematically met and interviewed every person he could who had any knowledge about the past.

Back in Greece, readers were eager to know all about the exotic land of Egypt, which was already surrounded by an aura of mystery and wonder at the time. And what they learned was even more amazing than they could have imagined, from the descriptions of the rock-cut tombs and monuments and the enormous pyramids to the Egyptian people’s strange worship of cats, to the fact that their gods were part animal, part human.

Other writers would follow suit, and later on, Hecateus of Abdera visited the land of the Nile (although his writings are now believed to be lost), as would Diodorus of Sicily, Plutarch, and the romance writer Heliodorus, among others. Even the Geography of Strabo owes much of its wisdom to the geographer’s visit to Egypt.

3. Philosophy: The Mysteries of Orpheus and Isis

For the ancient Greeks, it was common knowledge that Egypt was the fount of all wisdom and that such wisdom was quite ancient even then. It is no wonder, then, that popular myths told of the many philosophers’ formative travels to Egypt, even though most of them could not be confirmed historically.

The great Athenian statesman Solon was said by Herodotus to have visited Egypt at the time when Amasis II was Pharaoh. Plato probably set foot in the Land of the Nile around 393 BCE, and this is made evident in his dialogues, in which he claims that Egyptian tradition went back as far as 9000 years. Plato also describes in his Phaedrus how writing was invented by the Egyptian god Thoth. The scientists Thales and Pythagoras were said to derive most of their knowledge from their studies in Egypt, and from Plutarch, we would not have the famous Pythagorean theorem were it not for the influence of the Pyramids of Giza.

But Pythagoras did not just go to Egypt to learn maths. Supposedly, he also became initiated in the Orphic Mysteries, a doctrine that involved engaging in several secret rituals and purifying one’s soul and body through the adoption of ascetic practices. These practices were the ones that Pythagoras later taught his acolytes in the colony of Kroton, in modern-day Calabria, Italy. More popular among Greeks was the Mysteries of Isis, which became popular after the conquest of Alexander the Great. Isis was one of the main goddesses throughout Egyptian history and continued to be so in the Graeco-Roman Period.

4. The Calendar: Keeping Time in the Past

The ancient Egyptians developed a system for keeping track of the days that was revolutionary at the time. They were one of the first civilizations to notice the relationship between the movement of stars and other celestial bodies and the changes in seasons. For instance, they took notice of how the star that we now call Sirius would rise at the same time that the annual inundation began. The first appearance of said star in the sky happened every 365 days.

Eventually, 5,000 years before our day, they had already engineered a system that comprised 12 lunar months of 30 days, with 5 festive days at the end of the year. Each month was divided into three decans or 10-day weeks. We will speak more about these decans later on in this article when we discuss astrology.

Early Greek calendars were essentially the same as the Egyptian calendar (the first to adopt a solar calendar instead of a lunar one were the Romans). They even owed the Egyptians the invention of their most common method of keeping time, the clepsydra or water clock. Shadow clocks or sundials were much more reliable, but the Greeks found the clepsydra more practical as it could be transported. The main difference between the Greek and the Egyptian calendars was, along with the names of the months, the fact that Greek people identified each day of each month with a particular deity, and also there was a fixed relationship between calendar days and certain sports events.

5. Art: Statues and Their Poses

Among art historians, it was once common practice since the times of Johann Winckelmann to distinguish between the “naturalistic” style of Egyptian art and the much more refined and generally superior style of Greek art. However, nowadays this prejudice is contested and it is commonly accepted that Egyptian art was not inferior to Greek art and in fact the latter owes a lot to the former. For instance, the archaic monumental statues of young men known as kouroi (plural of kouros) provide evidence of Egyptian influence, not only in the proportions and techniques used but also in the posture of the human body as well.

Egyptian statues of standing men would invariably have the depicted individual standing not with the two legs parallel but with one foot forward. This created a sense of dynamism which was copied by the Greeks and perfected generation after generation. They eventually developed their own variant of this posture known as contrapposto. This posture involved the individual resting its weight on one of the legs, while the other leg remained bent and free. As different muscles were in tension on each leg, this forced Greek artists to meticulously study human anatomy and led classical Greek statues to have the appearance of dynamism and emotion that still amazes people around the world to this day.

6. Astrology: The Constellations We Know Today Were Born in Egypt!

To say ancient Egyptians were expert observers of the night sky would be an understatement. They knew the position and movements of each celestial body with astounding precision. Diodorus of Sicily even commented that the Egyptians could predict solar eclipses, something Greeks could not do at the time. It was only logical that they also produced a map of the sky, known as the zodiac, on the basis of knowledge inherited from the ancient Babylonians. The zodiac contained the twelve constellations that formed the 36 decans of each year. Each decan was represented by one particular star, and the whole system was based on the observation of the rising of the star Sirius.

Almost every constellation known to the Egyptians later had its correspondence with the Greek zodiac, and many of those kept the image the stars were supposed to form. For example, the stars that formed the Greek constellation of Capricornus were known in Egypt as the Goat and two stars that were known as “The Pair” in Egypt were called Castor and Pollux in the Greek zodiac, the mythical half-brothers who descended from Leda. According to myth, Pollux was a son of Zeus and thus immortal, while his half-brother was not. Pollux so wanted to keep close to his brother for all eternity that he asked his father Zeus to keep them together, so they were forever immortalized in the night sky as the constellation of Gemini.

7. Mythology: Egyptian Syncretism and Greece’s Appropriation

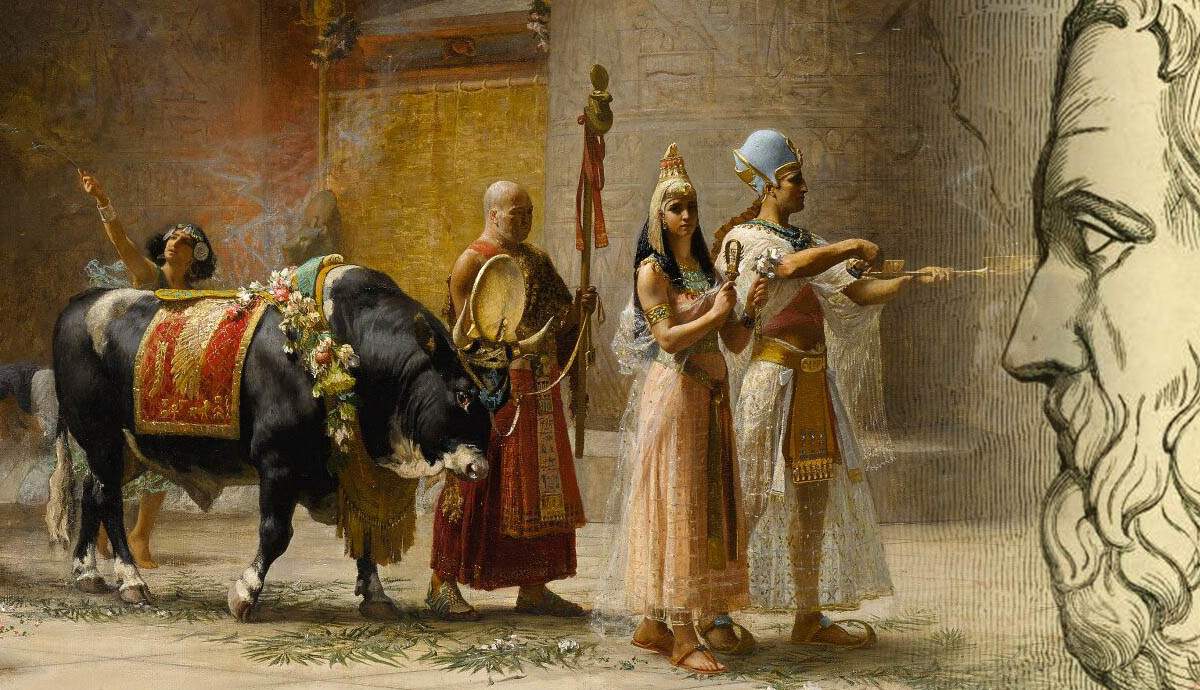

One of the most enduring aspects in which the Egyptian civilization influenced ancient Greece is also the most unexpected one — their religion. After all, the Greeks were the first ones to be surprised at the weird Egyptian gods with their animal heads and human bodies. However, this was not the complete picture, as Egyptian mythology and religion is incredibly rich and convoluted. Herodotus was the first chronicler to narrate the phenomenon known as syncretism, the identification of deities from different religions with one another. Syncretism was particularly important during the Hellenistic Period, after the conquests of Alexander the Great. Horus became Apollo, Ptah was Hephaestus, Isis became identified with Demeter, Neith with Athena, and so forth.

Gods in Egypt did not have just one appearance, but many. For instance, Thoth, the god of wisdom and mythical inventor of scripture, was represented either as a baboon, a human with an ibis’ head, or a complete human. It was this latter image that the Greeks took and adapted to their own religion, combining it with Hermes, giving birth to Hermes Trismegistos, or “Hermes the Thrice-Greatest.”

Another example of a mixed Greek-Egyptian figure who was worshipped not only in Egypt and Greece but in bordering countries such as Libya was Zeus Amun, a god that was already famous when Alexander the Great conquered the north of Africa. The main god of the Greek pantheon was combined with the main god in the Egyptian one, and it is shown in portraits as the typical Greek image of Zeus but with ram’s horns as Amun usually had. Alexander himself was sometimes represented with ram’s horns, a feature that shows how indebted the Greeks were to their Egyptian counterparts.