In the heart of the dense Amazonian jungle, researchers are realizing that what was long believed to be an untouched wilderness is anything but. Recent archeological discoveries indicate that the rainforest’s native populations spent centuries modifying and transforming the natural landscape. The so-called city-forest theory challenges traditional views of human-nature dynamics in the Amazon, suggesting that complex societies developed advanced landscape planning, built extensive networks of settlements, and created fertile lands that enabled them to thrive in a naturally harsh tropical environment—all achieved with sustainable practices.

The Amazon: Untouched Natural Landscape?

For years, traditional research on Amazonian history, inhabitants, and biodiversity revolved around ideas of a remote, untouched, and isolated rainforest. The concept of the Amazon as a “virgin wilderness” was widely accepted by 20th-century scholars and still remains prevalent among the general non-academic public.

These views were part of so-called environmental determinism, an anthropological theory that posits that human culture and societal development are shaped and constrained by environmental conditions. In places such as the Amazon, human agency and cultural development are seen merely as an adaptative response to the harsh tropical environment.

Environmental determinism was at the center of archeological and ethnographic studies in the Amazon until the late 20th century. Early scholars argued that the forest’s heavy rainfall, nutrient-poor soils, and dense vegetation created limitations that led to relatively small and dispersed communities.

From Remote Wilderness to City-Forest

The reality is quite the opposite. New archeological discoveries in the Amazon reveal that ancient societies actively managed the environment around them, creating complex settlement systems and sustainable agricultural practices that challenge the notion of a static, untouched wilderness.

This concept is encapsulated in the Amazon city-forest theory and rooted in some of the discoveries of the 1970s and 1980s when technological innovations allowed for new scientific insights by ethnobotanists, ethnographers, and cultural geographers.

With new methods available, archeological work was able to trace evidence of impressive structures within the Amazonian basin, such as geoglyphs, mounds, and extensive webs of earthworks, and deepen studies on archeobotanical remains. This enabled archeologists to perceive that human occupation in the Amazon is far from static but rather consists of intermittent periods of cultural development and adaptations.

View From Above: Aerial Imaging

Recent discoveries through aerial imaging and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology have significantly enhanced the understanding of settlement dynamics in ancient Amazonian communities. This remote sensing technology uses laser pulses to create high-resolution, three-dimensional maps of the ground surface, allowing archeologists to see through the dense layer of vegetation and uncover hidden features.

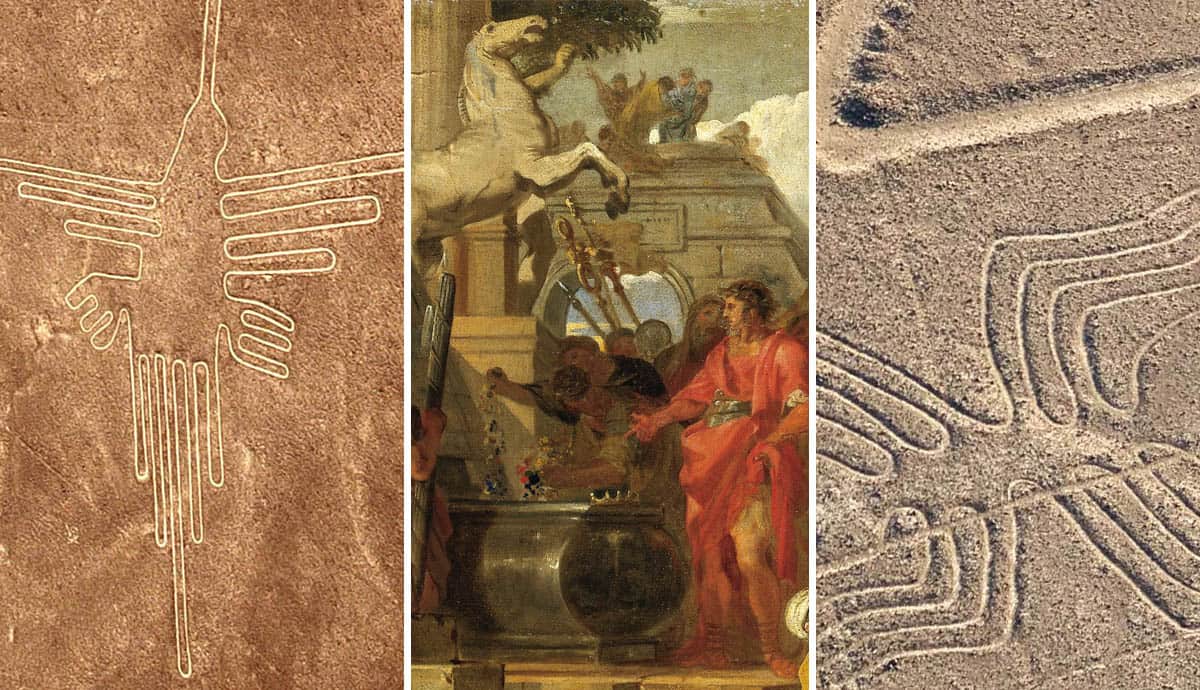

In the Amazon, LIDAR has been instrumental in revealing a vast network of earthworks and ancient settlements buried deep under the rainforest’s canopies. Among these fascinating discoveries are geoglyphs—large-scale geometric shapes carved into the landscape that include circles, squares, and complex interconnected patterns. They may also display potential symbolic meanings that hint at their use for ceremonial or political purposes. These structures can be as wide as 300 meters (980 feet), and the oldest structures date as far back as 1200 years.

LIDAR was able to spot evidence of large, interconnected settlements, which archeologists named Mound Villages. In the Brazilian state of Acre, in the southwest Amazon, a network of thousand-year-old Mound Villages was recently discovered over an older layer of geoglyphs dated between 400 BCE and 950 CE. They are uniquely shaped, made of circular mounds with roads radiating outward that give them a characteristic sun shape that may be connected to the sun-centered mythology of these peoples. This discovery challenges previous notions of the Amazon as sparsely populated; instead, it highlights the rainforest’s capacity to support a web of interconnected and complex societies.

Man-Made Soil: Agriculture Using Amazonian Dark Earth

Tropical soils are naturally nutrient-poor due to the intense leaching and erosive processes created by high temperatures, relative humidity, and heavy rainfall. But, the presence of highly fertile soils in the Amazon caught the attention of geologists and geoarcheologists; it suggests the use of agricultural practices that purposefully altered soil characteristics. Today, this soil is called terra preta, or Amazonian Dark Earth—a name given due to its typical dark color. These anthropogenic soils resulted from long-term soil management techniques and are produced by deliberate practices such as composting organic waste and mixing residues of charcoal, bones, broken pottery, and manure. Terra preta’s high organic and micro-organism content contributes to its rich nutrient profile that enabled the indigenous communities to sustain agriculture over long periods and thrive in a land not naturally suited for farming.

Some of the oldest samples of terra preta are estimated to date between 2,500 and 7,000 years ago, generally located near major rivers and their tributaries. It is believed that ancient societies likely used terra preta to support dense populations through sustainable agricultural practices, and so it is a testament to the existence of long-term human-nature interactions and alterations. Some of these techniques are still practiced by traditional communities, such as the Xangu, located in south-easthern Amazon.

Ancient Amazonians: Shaping Biodiversity

Archeobotanic research has also played a role in uncovering compelling evidence of ancient agricultural practices by pre-colonial Amazonians. Studies of ancient plant remains, such as seeds and pollen, reveal that these societies cultivated a diverse range of crops, including staple foods like manioc, maize, and sweet potatoes, enabled by the use of terra preta.

The discovery of the cultivation and domestication of plants that are not native to the Amazon directly impacts the understanding of the rainforest’s impressive biodiversity. Plant management techniques were responsible for the introduction of new plant species that contributed to the rich genetic diversity seen in modern Amazonian flora.

Furthermore, the creation of complex agroforestry systems that integrated crops with native tree species helped maintain and enhance biodiversity, creating diverse habitats and ecological niches. By transforming the landscape through their soil management and cultivation practices, ancient Indigenous peoples influenced the distribution and abundance of various plant species and contributed to current Amazonian biodiversity—often considered the greatest in the world.

Nature: The Ultimate Authority

Although these new findings point to a high degree of land management practices that directly transformed the natural landscape, such practices were undertaken in harmony with the environment. The religious conception of nature as a sacred and sentient being prevented the indigenous from harming it, respecting its individuality and autonomy. Scholars refer to the Amazonian model of human-nature interaction as “forest culture.”

For present-day Indigenous peoples, nature’s autonomy was not changed by these centuries of transformation. In fact, it was nature who taught humans how to develop ecological land management techniques—learned through active observation of the environment. This enabled humans to thrive in the forest while still maintaining ecological and sustainable practices, in contrast with many other regions where human development had harmful and irreversible effects on nature.

Ethnographic Work in the Heart of the Jungle

These new, exciting ideas were initiated through ethnographic and ethnohistoric research. These disciplines involve the observation of present-day traditional communities in an effort to identify cultural behaviors and technologies that could be traced back to the Indigenous communities of the past.

Native communities observed and assisted researchers in this ethnographic work, contributing their own perspectives to the identification of potential traces of human-environment interactions and sharing their insights, rooted in a deep understanding of these relationships. In undertaking this work, researchers were able to observe native peoples’ patterns and techniques for landscape management, concluding that purposeful alterations of the environment were widespread among the local communities.

This is relevant not only to achieving more meaningful results, but also to centering Indigenous populations in scholarly research. Their contributions enhance scientific work while enabling them to have an active voice and become protagonists in the production of knowledge.

Spread the Word: Publicizing Knowledge

Archeology still faces many obstacles in publicizing the discoveries and insights gained through scientific research. Reaching out to a wider audience is essential for several reasons, from combating fake news to breaking down stereotypes.

Ideas inherited from colonial-era myths are still widespread among the non-academic audience. Many people still portray Indigenous communities as primitive or static, holding on to the belief inherited from environmental determinism that these societies were isolated, unchanging, and less sophisticated than European civilizations.

These misconceptions affect Indigenous communities to this day as they struggle to make their voices heard and continue to fight for their rights. By highlighting the complexity and advancements of pre-colonial native societies, scholars can challenge these outdated views. Discoveries such as those made within the context of the Amazon city-forest theory reveal that Indigenous peoples were not only highly adaptive but also innovative. Publicizing these discoveries is crucial to correct the ongoing historical narrative and demonstrate that Indigenous cultures were—and still are—dynamic, complex, and culturally refined.

A New Understanding of the Amazon: Implications for the Future

These new findings have dramatically expanded modern understanding of pre-colonial Amazonian history. But there is still a lot to learn.

As remote sensing technology evolves, more features are expected to be discovered in lands still unexplored, uncovering more traces of settlements, geoglyphs, and roads. Further excavations and field surveys are also important steps in verifying the accuracy of the data captured by remote methods, essential to further testing and confirming these hypotheses.

Moreover, the increased deforestation created by the exploration of the forest for modern agriculture has put some of these discoveries at risk. The development of protective measures and legislation is crucial and will enable the safeguarding of the natural and anthropic features of this breathtaking landscape.

Learning from the Ancient Amazonians

Needless to say, these studies offer valuable lessons for modern man. Discoveries in the ancient Amazon provide interesting insights across different fields, from sustainable agriculture and environmental management to social organization and cultural resilience.

The creation and use of the highly fertile terra preta demonstrate sophisticated techniques for environmentally friendly soil enhancement. Plant domestication and ecosystem management practices created the fascinating and world-renowned Amazonian biodiversity of today, illustrating the profound impact of human activity on this fascinating ecosystem.

Recognizing these practices can foster more effective solutions to contemporary problems. Native Amazonians are demonstrating that innovation and sustainability can walk hand in hand, showcasing how an autonomous nature can coexist with human civilization and cultural development.

The Amazon is a model of cultural innovation that should serve as a framework for all humanity. It reveals that fostering development while minimizing human impact is not only possible but has already been done. The dense Amazonian rainforest is a complex and impressive testament to man’s ability to marry long-term transformation with ongoing conservation.