Art history scholars discuss Islamic works of art as those created in a world where Islam was a dominant religion or a major cultural force and not necessarily religious art. The term Islamic art references an artistic tradition spanning several continents and more than a thousand years of history. It includes work inspired by religious ideas and beliefs of Islam as well as art made in the lands held by Islamic rulers. As with any other style in art history, Islamic art differs through periods and countries. Despite the rich variety of artistic language and production, there are unifying elements that define Islamic Art. Islamic calligraphy, paintings, craftsmanship, and designs all show unique contributions by Islamic artists.

1. The Emergence of Islamic Art: Tradition & Originality

During its first centuries, the Islamic state slowly developed its own artistic tradition based on the styles and work of the regions it conquered. Examples of early Islamic art, such as the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque in Damascus demonstrate these integrations of the existing cultures. Main sources for Islamic artistic vocabulary came from the Coptic scrolling vines and geometric motifs of Egypt, Sasanian metalwork and crafts from what is now Iraq, and Byzantine mosaics depicting animals and plants. There was a balance between continuity and innovation, with new kinds of visual display, such as the decorative use of Arabic script, and technological changes in ceramics and glassmaking.

Thanks to the political fractures in the Islamic world during the Middle Ages, distinctive styles of this art began developing in different parts of the known world. Seljuq Turks of Iran developed mosques with a four-iwan plan, while Seljuqs in Anatolia made great strides in woodcarving, combining elaborate scrolling and geometric forms. In Cairo, Mamelukes built lavishly furnished mosques, madrasas, and mausolea; the art of the Moorish Iberian Peninsula was a space of unprecedented multicultural collaboration.

2. Islamic Art and Architecture

One of the earliest types of Islamic art that developed was architecture. Considering it is based on religion, Islamic art developed a unique type of religious architecture. Islamic temples are called mosques, or masjid in Arabic, and are used as gathering places of prayer, education (madrasah), and reflection.

The first mosque was the house of Prophet Muhammad in Medina, which was used as an example of a future mosque building. The architecture of the mosque, universal in function, does depend on the period and place where it was built, resulting in various styles, layouts, and decorations. A common feature of the mosque is an open courtyard, sahn, meant for holding a big population, and a big fountain used for ritual cleansing.

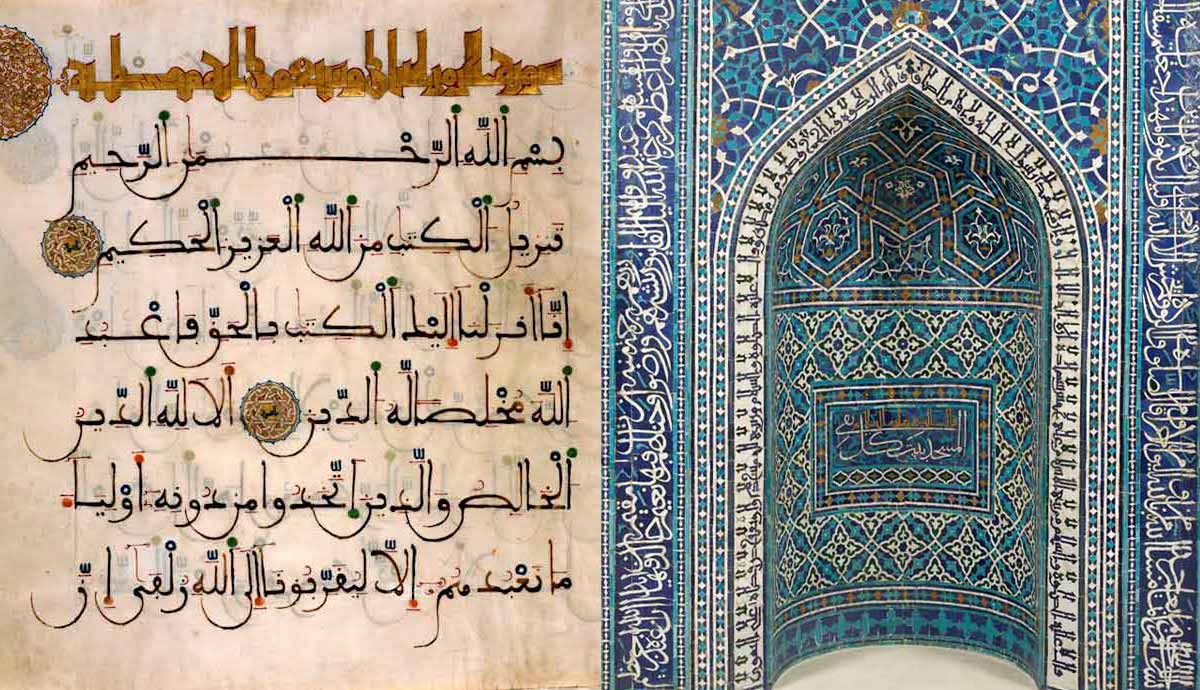

One of the most recognizable aspects of mosque architecture is the minaret, a tower from which the call to prayer is announced and a visual reminder of the presence of Islam. Most mosques have one or more domes, called qubba in Arabic. Coming from Byzantine architecture, it is a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven.

Inside the mosque, the essential element is the mihrab, a niche in the wall that indicates the direction to Mecca, towards which all Muslims pray. In Arabic, the direction towards Mecca is called qibla. Consequently, the mihrab is placed in a qibla wall, which is the most ornately decorated area of a mosque. Next to many other significant works of Islamic architecture, the Great Mosque of Samarra, the Great Mosque of Kairouan, and the Great Mosque of Cordoba are all recognized by UNESCO as World Heritage sites.

3. Lack of Figural Representation in Islamic Art: Real or Myth?

Al-Mas’udi, an Arabic 10th-century historian, describes the first documented mosaics decorating an Islamic building. The Kaaba, the holiest place in Islam, was decorated with mosaics taken probably from a Byzantine church in 684 but removed shortly after in 692. The importance mosaics held in the early centuries of Islam is seen by their use in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, built in the 690s. Wall and ceiling mosaics present vegetative motifs and scrolls, vessels, and winged crowns. As seen in the Dome of the Rock, the main characteristic of Islamic mosaics is the absence of figural representation in religious art. The resistance stems from the belief that the creation of living forms is unique to God.

It would be wrong to think that Islamic art is completely aniconic since private residences of sovereigns were filled with a variety of figurative paintings, mosaics, and sculptures. Qusayr ‘Amra was built in the 8th century as the desert residence of the Umayyad caliphs and a fortress with a garrison. The most important parts are the reception hall and the hammam (bath), both richly decorated with figurative frescoes. The dome with zodiac signs, human portraits, and depictions of animals in hunting scenes reflect early secular Islamic art.

4. Sculpture in Islam: Proving Misconceptions Wrong

Another proof that the idea of Islam banning figural representations is a misconception is the sculptural art commissioned by Islamic caliphs. The 8th and 9th centuries saw a renewal of ancient Greek and Roman sculptural traditions and classical mythological subjects. The Umayyad palace of Mshatta housed at least one statue that is still preserved and probably represents a personification of one of the seasons as a woman carrying a piece of fruit. In the carved stonework of Qasr al-Mshatta’s façade, we find representations of griffins, peacocks, lions, and pheasants among the grape leaves.

Figural presentations can also be seen in Islamic craftsmanship. Again, during the time of the Umayyad caliphs, a palace of al-Fudayn was built, which conserved a richly decorated bronze brazier. The palace is located on trade routes joining cities such as Gerasa (Jerash) with the Arabian Peninsula and belonged to the exceptionally wealthy great-grandson of the third Rashidun caliph ‘Uthman ibn ‘Afan. The brazier is decorated with Dionysian imagery. The figure of the god of wine, Dionysus, erotic cavorting maenads, satyrs, intimate couples, and Pan suggest the brazier may have been used in the bathhouse excavated at the Umayyad palace.

5. Calligraphy: The Highest Form of Art

The term calligraphy comes from the Greek words kallos (beauty) and graphos (writing) and refers to the harmonious proportion of both letters within a word and words on a page. Being closely related to the foundations of Islam itself, calligraphy is a fundamental element of Islamic art. Arabic calligraphy was given a universal status in Islamic culture since the Qur’an, the holy book of Islam, had been written and transmitted in it. The use of calligraphy as an ornament had an aesthetic appeal, but it also carried a talismanic element. Despite its decorative component, its primary function was to convey faith, legitimacy, and power. Calligraphers are held in high regard in Islamic culture, training rigorously and being highly educated. Most came from a family of calligraphers or the upper classes of society.

Calligraphy appears on both religious and secular objects in every medium: architecture, paper, ceramics, carpets, glass, jewelry, woodcarving, and metalwork. The first calligraphic script to gain prominence in Qur’an manuscripts, architecture, and portable works of art was Kufic and its variations. As with all types of Islamic art, calligraphy has its chronological and regional variations, with maghribi used primarily in Spain and North Africa, while nasta’liq was a script used in Iran and Central Asia.

6. Geometry & Infinity

One of the main decorative elements of Islamic art is geometric design. Basic geometrical designs come from the pre-Islamic artistic traditions of the Byzantine and Sasanian empires, adopted by 7th and 8th-century artists who gave them a new form and use. While these earlier traditions had a marginal use of geometry, Islamic artisans championed geometric designs, covering whole surfaces with them. This change is partially explained by the avoidance of figural forms in religious and public art. Most geometric patterns are derived from a grid of polygons, or regular tessellation, in which one regular polygon is repeated to tile the plane.

The ornamentation is based on the idea that every pattern can be repeated and infinitely extended, symbolically recalling the infinitude of Allah. An aspect of Islamic geometry is the basic symmetrical repetition and mirroring of the shapes that create a sense of harmony.

Most Islamic geometric designs are two-dimensional, rarely having shading or background-foreground distinction. In some rare cases, artists will create the illusion of depth and produce a visually pleasing and playful composition.

7. Arabesque: “In the Arab Fashion”

The most common motif in Islamic art of all countries and periods is the arabesque, a form of vegetal ornament composed of spiral or stylized waves and abstract elements. This term was coined in the early nineteenth century after Napoleon’s famed expedition to Egypt. The term arabesque simply means “in the Arab fashion” in French, and it is used only rarely by scholars of Islamic art.

The origins of Islamic arabesque can be found in the classical and Sasanian artistic traditions, and it acquired its typical shape in the 9th century under Abbasid rule. One of these examples of Medieval Islamic arabesque is the mimbar (a pulpit in a mosque where the imam stands to deliver sermons) of the Qayrawan Mosque in Tunisia, with tiles being imported from the Abbasid capital of Baghdad in the 9th century.

In this early period, arabesque is frequently combined with other motifs or calligraphy. One of the most common are birds, which are given an arabesque character through extreme stylization, particularly in the design of the wings. Just like geometric patterns, arabesque constitutes an infinite pattern that extends beyond the material world, symbolizing the infinitude and the nature of the creation of Allah. To the adherents of Islam, arabesque is symbolic of their united faith and the way in which traditional Islamic cultures view the world.