Pablo Picasso had a long and incredibly prolific career. Experts believe he created more than 100,000 pieces of artistic work. During his lifetime, he incessantly studied art of various cultures and periods, reviving and repurposing it for his avant-garde works. Based on particular influences, art historians usually divide his art into several phases, including the Blue, African, and Surrealist periods. In this article, we will take a closer look at the important stages of Pablo Picasso’s career.

1. Pablo Picasso’s Early Works

Pablo Picasso was born in 1881 in Malaga, Spain, and received his first artistic training from his father, who was an art teacher. In his teens, he began studying art professionally and demonstrated surprising attention to detail and thorough examination of works he copied. His training was based on examples from Antiquity and paintings of the Old Masters. Gradually, Picasso started to forge his own style, combining influences and ideas. During his trips to France, he studied the works of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and adopted elements of his style as well.

Picasso had a long and prolific career, which art historians usually divide into several phases. However, while attempting to dissect Picasso’s oeuvre into clear and precise stylistic periods, we should keep in mind that, in reality, the phases rarely replaced each other completely. Rather, they coexisted and occasionally re-emerged, often in surprising forms.

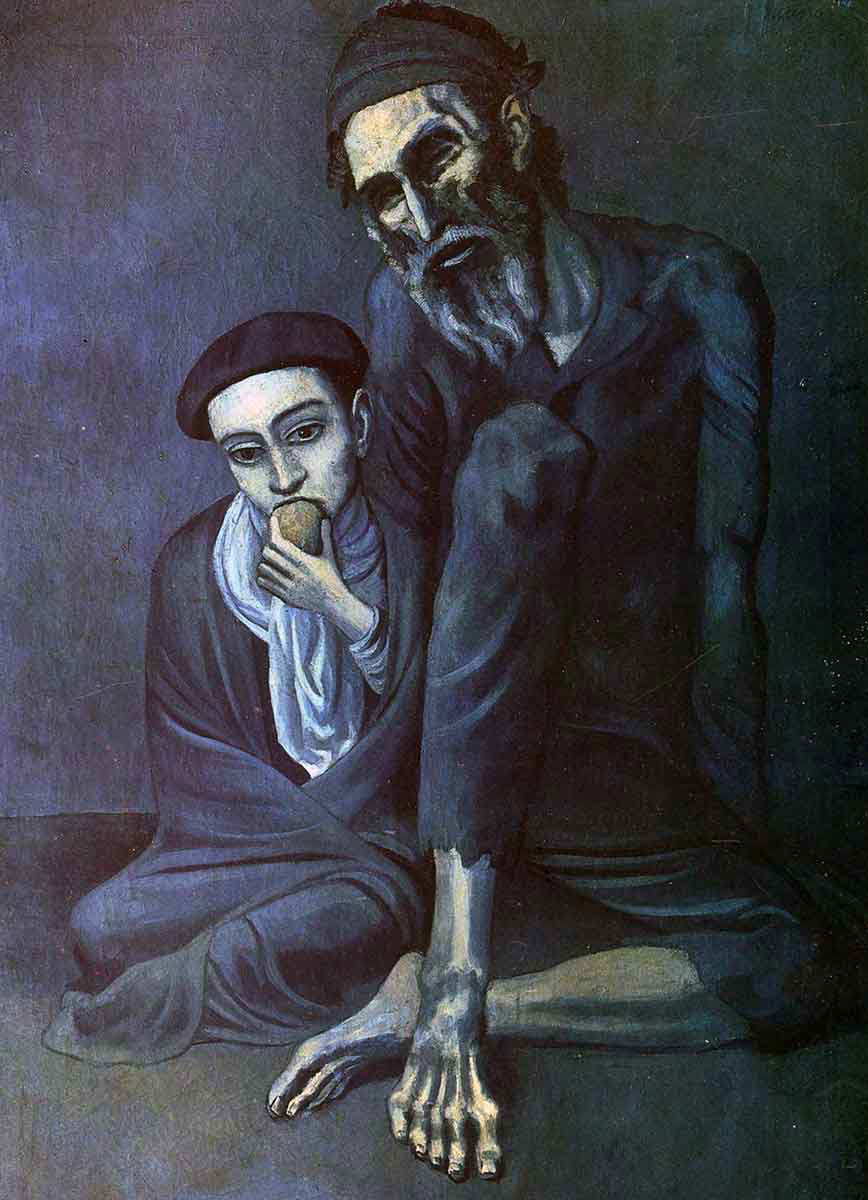

2. The Blue Period, 1901-04

Picasso’s Blue Period was the first instance in his career when he developed a distinctive style and consistent subject matter. In these three years, Picasso mostly used a somber palette of blues and greens and often painted impoverished street performers and bohemian alcoholics. This tragic tone was propelled by the suicide of Picasso’s close friend, Carles Casagemas, in early 1901.

At the time, Casagemas and Picasso, both Spaniards, tried to make ends meet in Paris. They lived in crushing poverty and attempted to earn a reputation as promising artists. These attempts were accompanied by substance abuse, alcoholism, and endless love affairs. Casagemas was desperately in love with a cabaret dancer, who rejected him on several occasions. After another bitter conversation, he invited her and their friends for dinner and shot himself in the head in front of the guests.

Picasso was not there to witness the death of Casagemas, but he was still immensely traumatized by the event. In the months following the unfortunate dinner party, he painted a series of works depicting Casagemas’ funeral. Depressed and impoverished, Picasso then identified himself with equally poor and permanently drunk cheap bar regulars, beggars, and outcasts, unfit for the urban world around them.

3. The Rose Period, 1904-06

After the gloomy and dark Blue period, Picasso emerged into the light, switching tones and exploring more hopeful subjects. Many art historians suggest that his depression, which lasted for three years after Casagemas’ death, was partially relieved by a new and exciting relationship. In August 1904, he met Fernande Olivier, a model who ran away from her abusive husband and settled in Montmartre.

Around the same time, Picasso also found an artistic community: he moved into the famous Bateau-Lavoir, a former piano factory squatted by artists and poets. Apart from Picasso, the long list of Bateau-Lavoir residents included Amedeo Modigliani, Juan Gris, Kees van Dongen, and Marie Laurencin. In that environment, Picasso moved from blues and greens to pinks and oranges. He still painted street performers—mostly acrobats—yet the undertone of the works became joyful. Instead of lonely figures, he focused on traveling groups dressed poorly but brightly, performing or recovering between the shows.

At the time, Picasso had a profound interest in Iberian sculpture, which was prominent on the Iberian peninsula from the Bronze Age until the territory was conquered by the Romans. He carefully studied the soft lines and stylization of the prehistoric works and applied them to his own compositions.

The artist himself did not make a distinction between his Blue and Rose periods. Rather, he believed they were part of a single artistic era. However, art historians separate the two, citing the radical change in the palette and the evidently cheerful tone of the Rose Period works. Starting from the Rose Period, Picasso gradually moved towards more abstract forms.

4. The African Period, 1906-09

Picasso’s interest in alternative artistic inspirations, such as prehistoric art, gradually led him to the exploration of sculptures from the African continent. African art arrived in Europe in the 1870s after the large-scale colonization unfolded. Precious objects were often looted from the homes and temples of locals and displayed in museums as weird artifacts of undeveloped nations. Picasso was one of the first figures in his generation to recognize these works as true art.

He realized that the artistic intention and visual language used by African artists radically differed from those employed by Europeans. He spent months carefully studying African works. He was particularly interested in wooden masks used in rituals and painted portraits with faces replaced by them. He also amassed a personal collection of African sculptures.

The most famous work of the African period is also the one that launched his later Cubist experiments. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon presented a group of sex workers with their faces covered with masks and bodies reduced to geometric figures. Picasso claimed that by studying African art, he realized that painting was not about beauty but rather about mastering one’s own fears and anxieties by giving them form. Still, Picasso’s treatment of African art was heavily criticized by art experts of later decades for excessive sexualization of figures and the juxtaposition of wild Africa to civilized Europe.

5. The Cubist Period, 1908-19

Picasso’s Cubist period, just like the art movement, was within itself divided into several distinctive phases. From the first experiments during his African period, he moved towards bolder and more complex experiments. The early stage of Cubism, usually called Analytical, was more radical and focused on deep intellectual dissection of space and form. Picasso and Georges Braque, another pioneer of the movement, carefully studied their objects from multiple points of view and angles. In order to get rid of all distractions, they limited the color palette to grays and browns. Cubist subject matter was also limited to still-life and occasional portraits of immobile seaters.

Synthetic Cubism was the following stage. Picasso was no longer content with the possibility of a flat-painted image. To construct a bridge between sober analysis and physical reality, Picasso began incorporating elements of collage, gluing newspaper clippings, wallpaper, and even chair seats to his canvases.

6. The Neoclassical Period, 1919-29

In the late 1910s, Pablo Picasso suddenly retracted his experiments and abandoned Cubism in favor of a style inspired by Classical art and its canons. At the same time, he traveled to Italy and studied the art of the Renaissance and Antiquity. Many artists shared an inclination towards a more conservative style of art at the time, and it even received its own art historical term. The so-called Return to order was collectively adopted by many avant-garde creatives, mostly those known for their radical experiments. Some Futurists, like Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini, reversed their creative directions towards more traditional art inspired by Italian tradition. The trend was mainly provoked by the shock of the war and the desire to reverse the events that led to the conflict.

7. The Surrealist Period, 1925-32

Picasso was never a full-blown Surrealist, although he spent many years interacting with the movement and adopting some of its elements. André Breton, the ideological leader of the Surrealists, was a great admirer of Picasso’s work and repeatedly asked him to join the movement. Although Picasso was interested in Surrealist symbols and imagery, he rejected the idea of unconscious creation. Primarily, Picasso was an intellectual artist who analyzed his subject before picking up the brush.

Picasso helped Breton with the publication of the Surrealist periodical Minotaure. His work at the time was balanced on the verge of abstraction. He painted portraits of women that almost collapsed into psychedelic mosaics of aggressive color. His geometric forms became more fluid, more aggressive, and less attached to reality, reaching Surrealist levels of absurdity.

8. Pablo Picasso’s Later Work

In the years that followed the rapid succession of artistic styles and influences, Picasso essentially combined all of them, creating diverse and complex art. His work remained stylistically the same, yet became more radical, sometimes to the point of being borderline caricature. As always, he experimented with mediums and formats. He even designed a chapel even though he was a Communist with a tense relationship to the Church.

Most art historians believe that the chapel design was Picasso’s reaction to a similar project by Henri Matisse, which triggered Picasso’s competitive spirit. In his later years, Picasso also contributed to the creation of innumerate forgeries of his own work. Concerned for the financial stability of his children, he left his signature on a stack of clear paper sheets. His idea was that his heirs could later draw or print something on them and sell these sheets as authentic works made by Picasso.