Charlemagne was one of the most powerful secular rulers, and art patrons, of the Middle Ages. His reign as Holy Roman Emperor resulted in a revival of art, learning, and literacy often called the Carolingian Renaissance. His surviving Palatine Chapel in Aachen, Germany is a perfect example of his classically-inspired values.

Charlemagne: The Frankish Holy Roman Emperor

The celebrated European ruler Charlemagne (c.742-814 CE), also known as Charles the Great or Carolus Magnus, started out his career as King of the Franks. The Franks were a Germanic tribe, one of many groups of non-Roman peoples who moved into areas like France, Italy, and Spain around the breakup of the western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE. Although they originally started out in what is now Germany, the Franks eventually settled in modern-day France, as their name suggests. Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, had been King of the Franks before him, after unseating the ruling Merovingian Dynasty. Pepin’s new dynasty is now called the Carolingian dynasty in honor of Charlemagne, by far its most famous member.

During his reign from 771 until his death in 814, Charlemagne consolidated most of Western Europe under his control, including modern-day France, Germany, much of Italy, and Northern Spain. He ruled a greater area of land than anyone had in Europe since the breakup of the Western Roman Empire; no one would again unite this much of Western Europe under one ruler until Napoleon about 1,000 years later. Charlemagne accomplished this through both political savvy and military skill in his numerous conquests.

Charlemagne was also a devout Christian. After coming to Pope Leo III’s military aid against the invading Lombards, Leo crowned Charlemagne as Roman Emperor in Rome on Christmas Day 800. This legitimized Charlemagne’s reign on a whole new level, putting a man the Romans would have considered barbarian on a par, at least in name, with the great Emperors of the classical Roman past. He spent the rest of his reign consciously aiming to live up to this role. In particular, he set himself up as successor to Constantine (c. 272-337 CE), the first Christian Roman Emperor, who legalized Christianity in 313 CE.

Charlemagne did much in service of making his empire a new and improved version of Christian Rome. He was hardly the only medieval leader who wanted to associate himself with all things Roman. There’s even a word for the Roman-like qualities he hoped to cultivate — romanitas. In this area, Charlemagne had some serious competition from the Byzantine Emperors, leaders of the Eastern Roman Empire who had a more direct claim to Constantine’s legacy than did Charlemagne. After all, their capital city of Constantinople had been founded by Constantine and named after him. Powerful Byzantine Emperors like Justinian I (reigned 527-565 CE) were also role models for Charlemagne, especially in the realm of art patronage.

The Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne lived and ruled in a period of European history when society, including art and learning, had declined substantially following the breakup of the Western Roman Empire. In his quest to create the perfect new Christian Roman Empire, Charlemagne took drastic steps to reverse this. He succeeded in creating enough political stability and centralized authority to enable a brief period of increased artistic, scholarly, and cultural production, often called the Carolingian Renaissance.

Charlemagne was keen to reform and standardize political structures, particularly the church. Doing this required a huge resurgence in literacy and learning, so that church leaders throughout his domain could quite literally all be on the same page. Although not particularly scholarly himself — his biographer, Einhard, tells us that he always struggled to write — Charlemagne encouraged learning and artistic production throughout his court and empire. He sought out the most brilliant scholars from all across Europe and gave them prominent positions in his court. He saw literacy and knowledge, especially amongst the clergy, as the best ways to promote healthy, unified, orthodox Christian practices. Even though it centered around only one segment of the population, the Carolingian Renaissance still represented the most significant uptick in literacy in centuries.

Charlemagne valued books, and he set up scriptoria in centers like Reims, Metz, and Aachen to produce them. Although the most luxurious manuscripts produced directly for him and his family are religious books, people working at these scriptoria also copied classical pagan texts. In fact, as much as ninety percent of the classical texts we know of today only survive because Charlemagne had his scribes copy them before the originals were lost. These texts were not only preserved, but also studied, corrected, and standardized by comparing different copies of the same text whenever possible.

The Carolingian Renaissance was so focused on the proliferation of knowledge that it even produced a new script, called Caroline Miniscule, which was designed for maximum clarity and legibility. It included then-unusual features we take for granted today, such as punctuation and spaces between words.

The invention of Caroline Miniscule points to an important aspect of Charlemagne’s reign. Although keen to associate himself and his empire with the glories of ancient Rome, Charlemagne’s goal was to build upon the Roman tradition, not just imitate or revive it. The term attached to his reign, the Carolingian Renaissance, casts it as prefiguring of the Italian Renaissance, a larger, later, and more permanent revival of classical ideals. However, the term has fallen somewhat out of favor with scholars, who now tend to prefer less dramatic characterizations, like the Carolingian Revival.

Charlemagne as an Art Patron

Alongside his interest in religion and learning, Charlemagne was also a great art patron, just as his Roman predecessors had been. He was not the first Frankish ruler to be associated with prestigious artwork. However, he commissioned objects in a more naturalistic, figurative Roman and Byzantine style instead of the flat, zoomorphic tradition of Germanic prestige metalwork favored by earlier Frankish kings.

Charlemagne did much to encourage the revival, however brief, of antique artistic styles and techniques. His art patronage connected him to the classical past of the Christian Roman Emperors through buildings, equestrian statues (a favored way of depicting military leaders), coins, metalwork, ivories, and illuminated manuscripts. He commissioned many Christian objects meant as royal gifts or contributions to significant religious institutions. The Carolingians founded and maintained close ties with key monasteries throughout their empire, many of which had dynasty members as their abbots or abbesses.

As befits a dynasty so strongly focused on Christianity and literacy, illuminated religious manuscripts are some of the most significant survivals of Carolingian art. Famous examples of manuscripts made for Charlemagne, his son Louis the Pious, and grandson Charles the Bald include the Godescalc Gospels, Ebbo Gospels, Gospel Book of Charlemagne, and the Utrecht Psalter. They were lavishly decorated with copious gold leaf, purple-dyed pages, bright colors, precious bindings, and full-page illustrations.

Carolingian Renaissance manuscripts combine naturalistic, antique-style figurative illustration with Germanic, Insular, and Byzantine influences. Carolingian patronage led to the development of court styles of art and illumination, such as the frenetic drawing style common to manuscripts painted in some Carolingian scriptoria. Their greatest scribes and illuminators were held in such high esteem that we still know their names today.

The Palatine Chapel in Aachen

At this time, Frankish kings and other Germanic leaders typically moved around their domains instead of settling down in a fixed capital city. Although Charlemagne did not really have an official capital either, he created a pseudo-capital in Aachen (also called Aix-la-Chapelle). He may have chosen this site, located in what is now Northern Germany, because he enjoyed its natural hot springs. Of the many buildings that once made up this imperial residence, only the Palatine (Palace) Chapel survives. Now Aachen’s cathedral, it is largely intact, though it has received additions in later centuries. Like everything else about Charlemagne’s reign, his Palatine Chapel tied him closely to the legacy of prior Christian Roman Emperors.

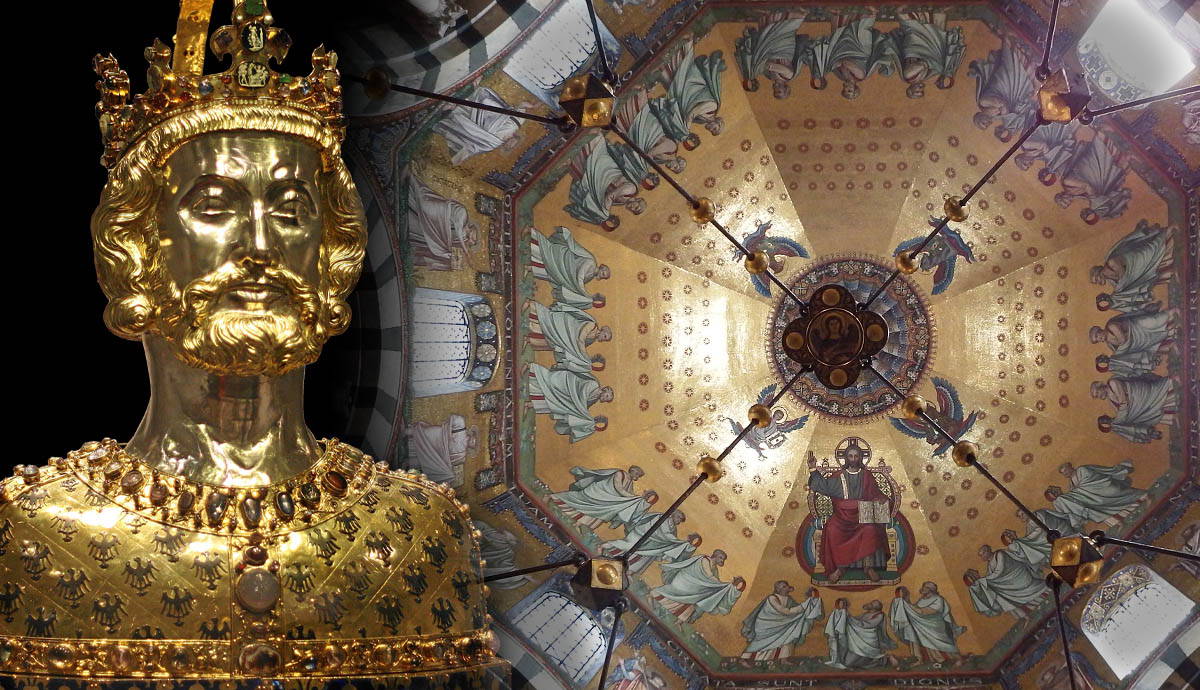

Designed by Odo of Metz (another Carolingian artists whose name survives today), the Palatine Chapel was consecrated in 805 CE and dedicated to the Virgin Mary. It is octagonal in shape, rather than the more typical rectangular basilica form. Although not particularly common for churches, this centrally-planned layout was popular for mausolea and martyria (tombs of martyrs), particularly the often-emulated Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Fittingly, Charlemagne is buried in his chapel.

The design of the Palatine Chapel is closely related to the centrally-planned church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. San Vitale was built in the 6th century, just before the Byzantine Emperor Justinian claimed this part of Italy for the Byzantines. Although Justinian did not originally commission the church, he had it decorated with a set of famous mosaics depicting Justinian and his Empress, Theodora, leading a glamorous church procession. Justinian and Theodore were great art patrons who also commissioned the Hagia Sophia, another centrally-planned church, in their capital city of Constantinople.

Like San Vitale, the Palatine Chapel has a domed, eight-sided central vessel surrounded by a vaulted ambulatory (aisle) and double-height gallery (mezzanine). However, their shared design has been somewhat simplified. The curved niches (exedrae) that connect the ambulatory to the main vessel at San Vitale have been flattened out in the Aachen version, and the arrangement of the arches has been reduced from three to one except on the top story. Additionally, the Palatine Chapel is constructed using different techniques and building materials than San Vitale. The fact that Western Europe did not, at this point, have access to the same caliber of artists that the Byzantines did may account for this simplification.

The Palatine Chapel has profuse, Byzantine-style decoration, including rich mosaics, bronze doors and railings, and multi-colored marble revetments. Following the examples of both San Vitale and the Hagia Sophia, whose marble revetments utilize book-matched marble, a technique in which a piece of marble is cut and then opened out to reveal mirror-image veining. Some of the building materials, particularly columns and their capitals, are spolia — re-used elements from older buildings in Rome and Ravenna.

The use of spolia was common in the classical and medieval worlds; it added prestige to a building by linking it with the venerated classical past. This fitted in well with Charlemagne’s ideals and aspirations. However, the Palatine Chapel’s imposing western facade has no close counterpart at San Vitale. This westwork contains an entrance and two spiral staircases to provide access upto the gallery level. In turn, the gallery was connected to the nearby palace and was only accessible to the most important members of court.

The Legacy of Charlemagne and His Palatine Chapel

Despite his achievements, Charlemagne’s power did not survive long after him. He was succeeded by his son, Louis the Pius, and then by a selection of grandsons and great-grandsons. Due to power struggles and territorial division between his heirs, his empire had fallen apart by about the year 900 CE. This did nothing to diminish his legacy. Like his hero Constantine, Charlemagne himself became a much revered and emulated historical ruler. Many later German rulers would follow in his footsteps by being crowned Holy Roman Emperor, the same position that Charlemagne held, although he would have not have used that exact title.

Tied as it was to Charlemagne’s legacy, his Palatine Chapel served as the coronation site for future Holy Roman Emperors until the 16th century. Accordingly, it received many lavish gifts from later emperors, include the Pala d’Oro and pulpit of Henry II, both gifts of the 11th-century Ottonian dynasty, the 12th-century chandelier of Frederic I Barbarossa, the 13th-century shrine of Charlemagne, and the added Gothic chapels.

Like many surviving medieval buildings, the Palatine Chapel has been modified and remodeled several times throughout its history. It was also damaged in a bad fire in the 17th century and gained some Baroque elements, since removed, during the subsequent restoration. Meanwhile, the imitator became the imitated, as the Palatine Chapel became a model for subsequent churches. It barely escaped obliteration during World War Two and has since been restored. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Even if you can’t make it to Aachen in person, you can still enjoy it though a 3D virtual tour.