Contemporary art is all about confronting the canon, representing a diverse range of experiences and ideas, utilizing new types of media, and shaking up the art world as we know it. It also mirrors modern society, offering viewers a chance to look back at themselves and the world they live in. Contemporary art feeds on diversity, open dialogue, and audience engagement to be successful as a movement that challenges modern discourse.

Black Artists And Contemporary Art

Black artists in America have revolutionized the contemporary art scene by entering and redefining the spaces that have for too long excluded them. Today, some of these artists actively confront historical topics, others represent their here-and-now, and most have overcome industry barriers not faced by white artists. Some are academically trained painters, others are drawn to non-Western art forms, and yet others defy categorization altogether.

From a quilt-maker to a neon-sculptor, these are just five of the countless Black artists in America whose work showcases the influence and diversity of Black contemporary art.

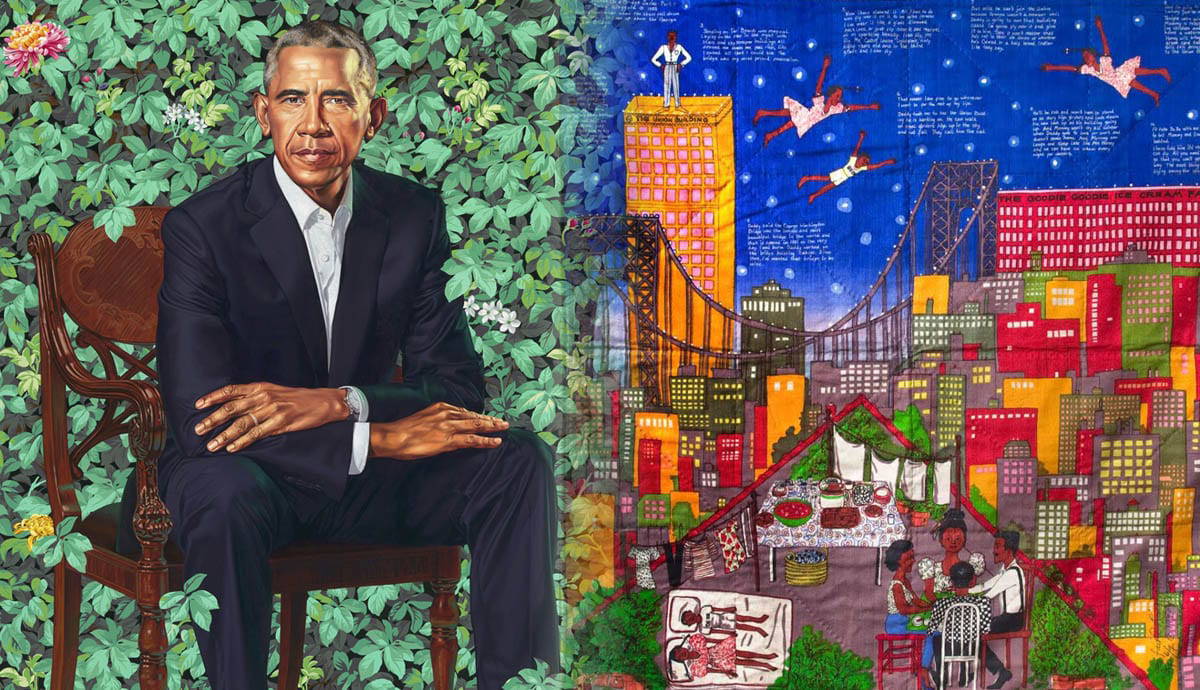

1. Kehinde Wiley: Contemporary Artist Inspired By Old Masters

Most famous for being commissioned to paint the official portrait of President Barack Obama, Kehinde Wiley is a New York City-based painter whose works combine the aesthetics and techniques of traditional Western art history with the lived experience of Black men in twenty-first-century America. His work depicts Black models he meets in the city and incorporates influences the average museum-goer might recognize, such as the organic textile patterns of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts Movement or the heroic equestrian portraits of Neoclassicists like Jacques-Louis David.

In fact, Wiley’s 2005 Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps is a direct reference to David’s iconic painting Napoleon Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard (1800-01). Of this kind of portrait, Wiley said, “It asks, ‘What are these guys doing?’ They’re assuming the poses of colonial masters, the former bosses of the Old World.” Wiley utilizes familiar iconography to imbue his contemporary Black subjects with the same power and heroism long afforded to white subjects within the walls of Western institutions. Importantly, he is able to do this without erasing his subjects’ cultural identities.

“Painting is about the world that we live in,” said Wiley. “Black men live in the world. My choice is to include them.”

2. Kara Walker: Blackness And Silhouettes

Growing up as a Black artist under the shadow of Georgia’s Stone Mountain, a towering monument to the Confederacy, meant that Kara Walker was young when she discovered how the past and the present are deeply intertwined—especially when it comes to America’s deep roots of racism and misogyny.

Walker’s medium of choice is cut-paper silhouettes, often installed in large-scale cycloramas. “I was tracing outlines of profiles and I was thinking about physiognomy, racist sciences, minstrelsy, shadow, and the dark side of the soul,” said Walker. “I thought, I’ve got black paper here.”

Silhouettes and cycloramas were both popularized in the 19th century. By utilizing old-fashioned media, Walker explores the connection between historical horrors and contemporary crises. This effect is further emphasized by Walker’s use of a traditional schoolroom projector to incorporate the viewer’s shadow into the scene “so maybe they would become implicated.”

For Walker, telling stories isn’t just about relaying facts and events from start to finish, like a textbook might. Her 2000 cyclorama installation Insurrection! (Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On) is as haunting as it is theatrical. It uses silhouetted caricatures and colored light projections to explore slavery and its ongoing, violent implications in American society.

“There’s a too-muchness about it,” said Walker in response to her work being censored, “All of my work catches me off guard.” Walker has been met with controversy since the 1990s, including criticism from other Black artists due to her use of disturbing imagery and racial stereotypes. It could also be argued that provoking a strong reaction in viewers, even one that is negative, makes her a decidedly contemporary artist.

3. Faith Ringgold: Quilting History

Born in Harlem at the height of the Harlem Renaissance, a movement that celebrated Black artists and culture, Faith Ringgold is a Caldecott-winning children’s book author and contemporary artist. She is best known for her detailed story quilts that reimagine representations of Black people in America.

Ringgold’s story quilt was born out of a combination of necessity and ingenuity. “I was trying to get my autobiography published, but no one wanted to print my story,” she said. “I began writing my stories on my quilts as an alternative.” Today, Ringgold’s story quilts are both published in books and enjoyed by museum visitors.

Turning to quilting as a medium also gave Ringgold the chance to separate herself from the hierarchy of Western art, which has conventionally prized academic painting and sculpture and excluded the traditions of Black artists. This subversion was especially relevant for Ringgold’s first story quilt, Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima (1983), which subverts the subject of Aunt Jemima, a storied stereotype that continues to make headlines in 2020. Ringgold’s representation transforms Aunt Jemima from a slavery-era stereotype used to sell pancakes into a dynamic entrepreneur with her own story to tell. Adding text to the quilt expanded upon the story, made the medium unique to Ringgold, and took one year to craft by hand.

4. Nick Cave: Wearable Textile Sculptures

Nick Cave was trained as both a dancer and as a textile artist, laying a foundation for a career as a contemporary Black artist who fuses mixed media sculpture and performance art. Throughout his career, Cave has created over 500 versions of his signature Soundsuits—wearable, mixed-media sculptures that make noise when worn.

The Soundsuits are created with a variety of textiles and everyday found objects, from sequins to human hair. These familiar objects are rearranged in unfamiliar ways to dismantle traditional symbols of power and oppression, such as the Ku Klux Klan hood or the head of a missile. When worn, the Soundsuits obscure the aspects of the wearer’s identity that Cave explores in his work, including race, gender, and sexuality.

Among the work of many other Black artists, Cave’s first Soundsuit was conceived during the aftermath of the police brutality incident involving Rodney King in 1991. Cave said, “I started thinking about the role of identity, being racially profiled, feeling devalued, less than, dismissed. And then I happened to be in the park this one particular day and looked down at the ground, and there was a twig. And I just thought, well, that’s discarded, and it’s sort of insignificant.”

That twig went home with Cave and literally laid the foundation for his first Soundsuit sculpture. After completing the piece, Ligon put it on like a suit, noticed the sounds it made when he moved, and the rest was history.

5. Glenn Ligon: Identity As A Black Artist

Glenn Ligon is a contemporary artist known for incorporating text into his painting and sculptures. He is also one of a group of contemporary Black artists who invented the term post-Blackness, a movement predicated on the belief that a Black artist’s work does not always have to represent their race.

Ligon began his career as a painter inspired by the abstract expressionists—until, he said, he “started to put text into my work, in part because the addition of text literally gave content to the abstract painting that I was doing—which isn’t to say that abstract painting has no content, but my paintings seemed content-free.”

When he happened to work in a studio next door to a neon shop, Ligon began making neon sculptures. By then, neon was already popularized by contemporary artists like Dan Flavin, but Ligon took the medium and made it his own. His most recognizable neon is Double America (2012). This work exists in multiple, subtle variations of the word “America” spelled in neon letters.

Charles Dickens’ famous opening line to A Tale of Two Cities—“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”—inspired Double America. Ligon said, “I began thinking about how America was at the same place. That we were living in a society that elected an African American president, but also we were in the midst of two wars and a crippling recession.”

The title and subject of the work is literally spelled out in its construction: two versions of the word “America” in neon letters. Upon closer observation, the lights appear broken—they flicker, and each letter is covered in black paint so that light only shines through the cracks. The message is two-fold: one, spelled out literally in words, and two, explored through metaphors that hide in the details of the work.

“My job is not to produce answers. My job is to produce good questions,” said Ligon. The same can likely be said for any contemporary artist.