Shrunken heads fascinated the western pallet for hundreds of years, ever since the first encounter with the cultural phenomenon in South America. Europeans quickly started to amass collections of these heads and added them to their curio-cabinets along with other macabre artifacts from different cultures around the world. They sat alongside mummies from Egypt and, of course, heads from the Pacific. Oceania did not have “shrunken heads” like those found in South America. However, in New Zealand, there were numerous examples of similar cultural practices called mokomakai.

How to Shrink a Head

Shrinking a head is much easier than you might think, although it is quite gruesome. Firstly, the skin and hair must be separated from the skull to maximize the amount of “shrinkage.” This is followed by the eyelids sewn shut and the mouth closed with a peg. Finally, the shrinking can begin as the head is put into a boiling pot for a certain period of time.

When the head is removed, it will be about one-third of its original size with dark and rubbery skin. This treated skin is turned inside out, and any leftover flesh is scraped off before it is folded back. The left-over skin is then sewn back together. But this is just the start.

The head is then dried out further by inserting hot stones and sand to cause it to contract inwards. This tans and helps preserve the skin, much like leathering animal skin. Once the head is at the desired size, the small stones and sand are removed, and even more hot stones are applied this time to the outside. The application of these helps seal the skin and shape the features. Finally, the exterior skin is rubbed with charcoal ash to darken it. This completed product could be hung over a fire to harden and blacken further, and then the pegs holding the lips could be removed.

Why Shrink a Head? Aotearoa: Mokomakai

Māori preserved heads were sacred in cultural ceremonies, and with European contact, they became unlikely valuable trade items. By the time of the Musket Wars of the 19th century, they were used for trading for guns and thus became “easy artifacts” to be acquired by collectors. But even before western collectors became drawn to the dead remains of other cultures, the head held certain purposes to the Māori, who practiced this tradition of head preservation through shrinking.

The act of Mokomakai was mainly reserved for men of high status who wore full moko tattoos on their faces. This included the chief of the tribe making the head to preserve their likeness in death or from the enemies kept and displayed as trophies of war. However, some high-ranking women would be sometimes gifted this honor in death if they too had moko on their faces. The preservation of their faces ensured not just their identity living on but their tattoos which were spiritual ties to their whakapapa (ancestors, cultural, and tribal roots).

Mokomakai was a common practice but ended soon after the European settlement of Aotearoa. This led to the abolishment of head shrinking in their cultural traditions of war and commemorating the dead.

The New Zealand History Podcast has a brilliant 34-minute episode discussing Mokomakai in greater detail here: Preserving the Past – History of Aotearoa New Zealand Podcast (historyaotearoa.com)

Why Shrink a Head? Outside of New Zealand

Outside of New Zealand, there are few examples of other shrunken head cultural practices in the Pacific. But going further afield to South America is where this tradition was alive and practiced at the same time. For when Māori practiced Mokomakai, the Shuar people practiced tsantsa.

The Shuar people believed that there were many different types of souls, and the most powerful was the vengeful soul. So, if someone was killed in battle, the biggest worry was that the soul would come back for revenge against their murderer beyond the afterlife. Therefore, to ensure that this did not happen, the soul had to be trapped in the head, for that is where it resided. This could be done by shrinking the head.

Could there be a link between the cultural phenomena of shrinking heads in the Americas and the Pacific? It can’t be ruled out that these aren’t unique cultural traditions that developed independently of each other. However, Polynesians did trade some cultural products with indigenous people of the Americas. This is best seen in the example of the introduction of sweet potato to the Pacific from these networks. So, what is to say the Māori did not become inspired by cultural practices as well?

The European Fascination With Mokomakai

Even today, people from all over the world are likely quite fascinated by the macabre subject of shrunken heads. It is not too dissimilar to the way westerners thought about the artifacts of the cultures that made them and thus felt inclined to trade for them.

European museums displayed prime examples from their vast collections of shrunken heads collected over the years, particularly during the 18th and 19th centuries. They obtained these heads through trade networks established between voyagers to the Pacific and often obtained them at a bargain price from the culture they purchased them from. The specimens would be taken back to Europe, where collectors paid top dollar for them.

With such a desire for these artifacts, Māori met the demand by making more. Instead of being simply sacred remains of their ancestors, the shrunken heads evolved into artifactual commodities. Purchasing European goods, including guns, aided in defending themselves during the New Zealand Wars.

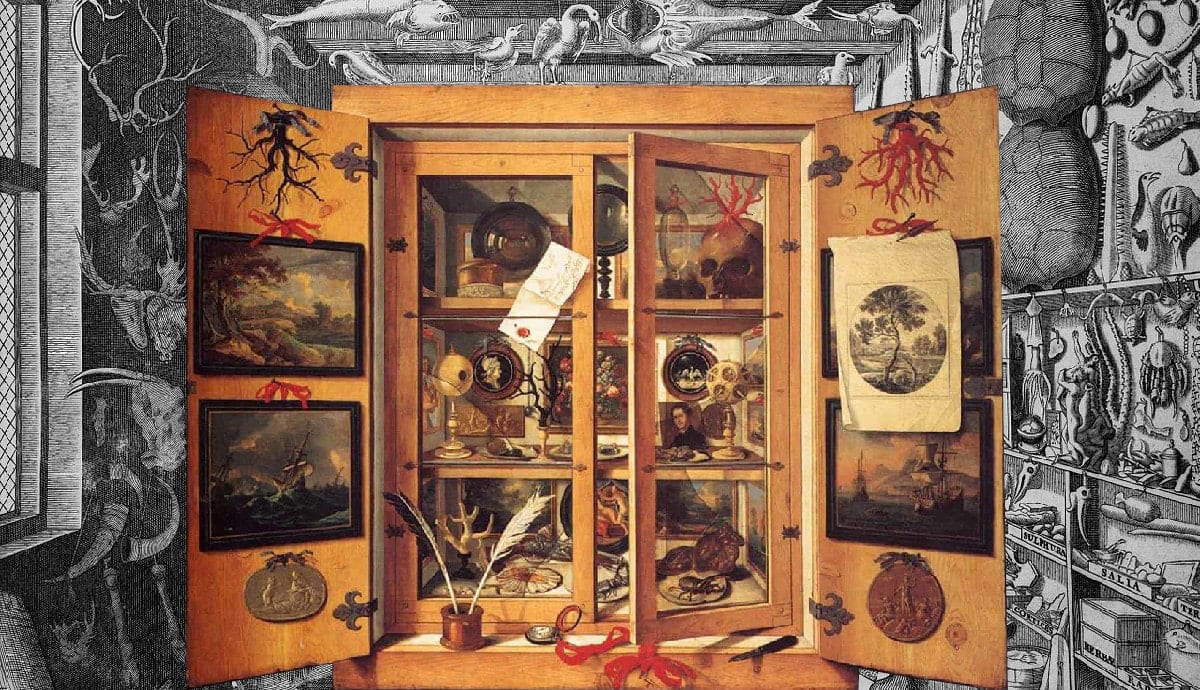

The heads were displayed as artifacts alongside other curio objects taken from the “New Worlds” in cabinets of the wealthy and elite to show off to their friends. They were regarded as simply physical objects with a distant connection to “others,” from a land they likely would never visit nor have the drive to learn about. Thus, shrunken heads became removed from their cultural contexts and transformed into objects to gawk at. Their original human and spiritual connection was severed.

Repatriation of Shrunken Heads & Other Cultural Heritage

Since the late 1900s, steps have been made by Māori to repatriate the remains of their ancestors, which are held in collections around the world. The Pitt Rivers Museum at one time held a large collection of shrunken heads on display. In 2020, it made the decision to remove the cabinet from public display. This decision was made as the curators came to realize that the display enabled racist stereotypes instead of teaching the public audience about the true cultural contexts for their objects.

Steps like the Pitt Rivers Museum’s actions have been made in recent years by museums and collective groups representing the ancestors of these artifacts to decolonize museum collections. In the case of Mokomakai, repatriation efforts have been largely successful in the return of ancestral remains back to their iwi. In 2017, several shrunken heads were returned from museums and private collections around the world to New Zealand and were met with emotional celebrations.

However, despite the calls and the successful attempts to return some of these heads, there is still a long journey ahead for Māori and other cultures who still have sacred ancestral remains hauled up in storage or public collections around the world. Te Herekiekie is a recognizable spokesperson in this regard. He wants those not listening to know to their calls that these remains are not artifacts, but people, their sacred ancestors.

Shrunken heads are not a common cultural practice in the Pacific, being exhibited only in New Zealand with the Māori traditions of mokomakai. However, these heads are still cause for appreciation and study as they help understand the culture and history of the Māori people and what makes them unique compared to other parts of the wide Polynesian family.

The similarities to cultural practices in South America allow one to ask whether the cultural practice of head shrinking developed independently between the two cultures. Was mokomakai developed under the unique context of the Māori culture in New Zealand or because of previous contacts with inhabitants of South America? The answer is most likely due to independent means, but it is important to be aware of all possibilities. Seeing as Polynesians traded for sweet potato, they likely exchanged ideas and cultural practices as well.

With the rocky relationships with European settlement of the 19th century and the subsequent wars, peace has returned to the islands of the long white cloud, and kiwis are working together to write the wrongs of the past. International efforts are also underway to repatriate sacred ancestral objects from museums back to their rightful resting places in the waka of their homelands.