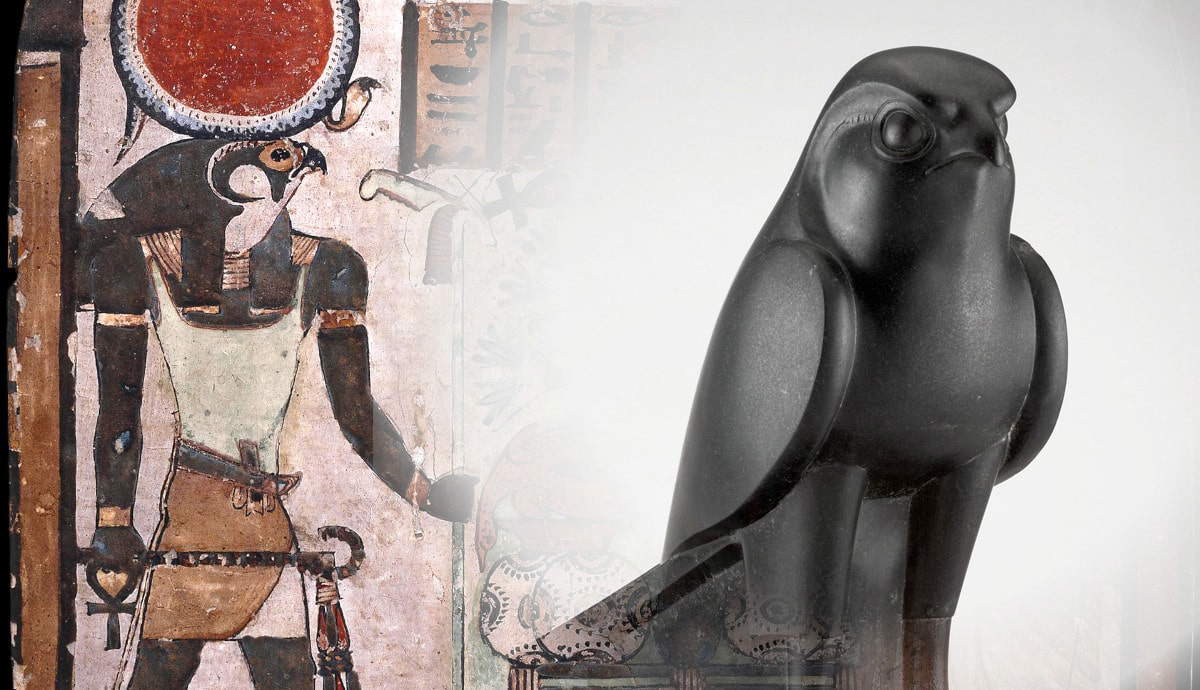

Ancient Egyptian mythology tells of the first moment in time when the first land emerged from Nun, the dark and endless waters in which nothing existed. A falcon (a form of the sun god and closely associated with the king) or a benu-bird (a phoenix-like creature representing the creator god Atum) alighted upon the mound, and so sparked the creation of the world. These actions are at the center of Ancient Egyptian belief in their gods and the divinity of the king. These concepts and imagery can be seen in the earliest sacred spaces dating to the fifth millennium BCE, well before the beginning of what we generally recognize as the pharaonic period.

Excavations have revealed foundations, deposits, structures, and artifacts technologically and stylistically similar to much later examples, down to the 4th century CE when Egypt was under Roman rule. Elements of temple architecture, artistic styles, royal practices, and more changed, but at the heart of it all, certain concepts and beliefs remained constant.

Hierakonpolis: Ancient Egypt’s First Power Center

One of the most famous artifacts from Ancient Egypt is the Narmer Palette. It was assumed for a long time that it showed the act of unification between the north and south of Egypt, but recent scholarship indicates that the emergence of the state did not happen as a single event. However, the findspot of the Palette is still regarded as one of the most important sites in the entire history of Egypt. The city of Hierakonpolis (ancient Nekhen) is where we see some of the earliest evidence of the relationship between state and religion, c. 3100 BCE — a cult center of the falcon god, Horus.

Hierakonpolis was excavated in the late 19th century CE by James Quibell (1867-1935) and Frederick W. Green (1869-1949). Their work revealed an extensive ritual landscape spanning the river Nile, with settlements and ceremonial areas focusing on a temple complex. The finds included an exquisite gold falcon statuette, a copper statue of a king, the ‘Scorpion Macehead’, and the Narmer Palette. The quality of these artifacts, their deposition in a clearly delineated sacred area, and the imagery of kingship together confirmed Hierakonpolis and its temple as the primary focus of the ruling class. Excavations at the site continue today under the direction of the Hierakonpolis Expedition.

Saqqara: the first pyramid complex

Pyramids are not individual, stand-alone monuments, but are part of much larger complexes which include temple structures. Saqqara was the setting for an escalation in the presentation of power and prestige, and innovation in how the king’s mortuary cult was celebrated — while retaining the fundamental mythological and religious themes established at Hierakonpolis.

The Step Pyramid, constructed around 2650 BCE, was the world’s earliest building in stone, the design attributed to king Djoser’s master architect, Imhotep. The impact of this achievement ensured Imhotep’s immortality, with his deified image still present centuries later, worshiped as a patron of craftsmen, architects, magicians, etc.

The earlier form of elite tomb took the shape of a large structure known as a mastaba (Arabic for ‘bench’). The upper part was where storage chambers and the presentation of the life of the deceased were laid out, along with a tomb chapel for visitors to bring offerings. Below ground was the burial chamber, not intended to be accessed after being sealed off. Some of these mastabas are immense, with many rooms and exquisitely painted reliefs. The Step Pyramid developed from this style, with graduating layers reaching towards the sky, reinforcing the belief that the king would return to the stars. The pyramid was enclosed by a boundary wall to separate the sacred space from the outside world, and shrines and ceremonial spaces allowed the king to demonstrate his dominion over the land of Egypt and his continuing fitness to rule in life.

The Scorpion Macehead from Hierakonpolis shows aspects of this ritual, again confirming that the rules of art and power were established long before. The Valley Temple was a processional way which enabled maintenance and access for those permitted. After Djoser’s death, the complex continued to be used in ceremonies celebrating the now fully divine king in his own right and as part of an enduring lineage that stretched back to the dawn of time and was intended to last for eternity.

Giza: The Pyramid Age

The Giza Plateau, with its magnificent pyramids dominating the skyline, was the culmination of these earlier ideas. Variations, such as the so-called ‘Bent’ Pyramid at Dahshur, the pyramid at Meidum, and the slightly later ‘Sun Temples’ at Abusir likely show further experimentation, but the three iconic pyramids of the kings Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure are the most impressive and well-preserved manifestations of the power of Egypt, the religious ideas which placed the king at the beginning of creation, and that continuing legacy enduring for all time. The Great Sphinx has stood watch before the pyramids since c. 2550 BCE, itself a symbol of the dual nature of the king — mortal and immortal, with the wisdom of his divinity and the invincibility of his earthly form.

Khafre’s Valley Temple is made with limestone from local quarries and granite from Aswan, 1000 miles to the south, representing his control of all of Egypt and a statement for the gods — the finest stone and craftsmanship are dedicated to the temple, which was intended to last forever, like the king himself. The image of the king was also replicated in statue form to encapsulate these same ideas.

Thebes: Re-unification and Expansion

A shift in religious beliefs away from a core focus on the sun led to later alterations in the design of temples, as well as a change of primary location. Previously, the most important religious buildings were in the Memphis and Saqqara area, but political events, the undulating balance of power, and a need to reconcile these changes without compromising on tradition and belief saw new building projects around Thebes (modern Luxor).

The symbolism of the earliest times, the traditions established in the Pyramid Age, and the progression on the world towards New Kingdom Egypt (c. 1550-1070 BCE) resulted in temples of great beauty and complexity, probably best seen in the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. The temple and its precinct were modeled after the one directly beside it — that of the great unifier of the Middle Kingdom, Montuhotep II, which incorporated (for the first time) the actual burial space of the king and his family and his mortuary temple space. Religious beliefs were shifting towards a system focusing more on the concept of an underworld afterlife, and the association of the dead with the god Osiris.

Therefore, Hatshepsut’s temple was designed with elements of Predynastic/Old Kingdom ritual space — the primeval mound, possibly topped with an obelisk or pyramid capstone; lines of sycamore trees, sacred to the goddess Hathor, whose cult was already ancient; and the rising causeway emulating the Valley Temple and the primeval mound.

The Middle Kingdom was represented in the emulation of Montuhotep II; the proximity of another great king’s statues in the wider complex — those of Senwosret III; and the continuation of archaism from the Old Kingdom. Hatshepsut was stepping into a new age of prosperity, and her temple was a statement of her status as the latest in the long line of rulers of Egypt, being divine of birth, powerful, and accomplished. The reliefs of her famed voyage to the land of Punt are typical of mortuary temples, which are designed to not only celebrate the late king’s life, but to record their achievements and offer them to the gods, with whose beneficence they have succeeded.

The Great Temples of Karnak and Luxor

Like Deir el-Bahri and others before it, the temples of Karnak and Luxor were built for the practicalities of life as well as the worship of gods and the king. The temples were connected by processional routes, and the area was the largest religious complex in the world. At the heart of Karnak was the precinct of Amun-Ra, the principal god of Thebes and ‘Lord of All,’ although other gods were represented in and around the main temple. Karnak’s origins dated from the Middle Kingdom, being a sacred space built upon and expanded over time by many rulers. Thebes (ancient Waset) was now the political capital, and the temple was the setting for processions, ceremonies, proclamations, and the official machinations of justice, administration, and the economy, as well as worship.

Priests had a lot of control in Thebes because of their close relationship with the temple as the center of power, and eventually the High Priests of Amun became de facto rulers in the south not too long afterwards. Karnak also had segregated areas, becoming more restrictive the further one went into the temple. Today, Karnak and Luxor are open to the skies, and there are no barriers to exploring; in ancient times, it would have been roofed, with great doors at the entrance and inside.

Architecturally, Karnak and Luxor maintained the by now millennia-old features of the oldest religious spaces — rising floors and columns, shaped like papyrus and lotus plants; in fact, before the construction of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s, the annual flooding of the Nile partially submerged the temples in a recreation of emergence of life from the waters of Nun. Other features included orientation to the cardinal directions, and a duality to decoration and inscriptions representing the two ‘halves’ of Egypt. This duality extended to the sky and the earth, the river and the desert, the living and the dead, and the divine/mortal nature of the king. Many such reliefs and scenes have a ‘mirror’ scene, perhaps on the opposite wall or even at the other side of the temple.

Furthermore, mortuary temples are usually on the west bank of the Nile, in the land of the dead, where the sun sets; other types, such as those dedicated to a god, tend to be on the east, where the sun rises.

The great walls of the temples were decorated with scenes of triumph, such as pharaoh returning from battle to present captives to the gods, bringing exotic goods, showing the spoils of war and the execution of prisoners. Whereas the inner parts of the temple reflected the restricted, inaccessible aspects of the king and his power, and his relationship with the gods, the outer areas were his public face, shown as powerful, undefeated, merciless, wealthy, possessing the blessing of the gods and, therefore, so was Egypt itself.

The Last Temples

The most well-preserved temple today is that dedicated to the god Horus at Edfu. Construction began around 237 BCE in the reign of Ptolemy III, and it is a testament to the endurance of Ancient Egyptian beliefs. The extant buildings and remains confirm that the practices and beliefs, and the presentation of the king and the gods, had changed very little overall. Even the Greek and Roman rulers depicted themselves as rulers of Egypt in the standard fashion, with their own decorative adjustments to suit their origins.

The temple remained as the cultural center of society, from the Predynastic Period through to the decline of temple use in the 4th century CE. Those from the Graeco-Roman Period tended to be smaller versions of their earlier models.

That they have such appeal to visitors today is a testament to their magnificence and encapsulation of the hallmarks of this ancient civilization, which are still so present in the landscape and in the cultural heritage of modern Egyptians.