Vanitas was a popular theme in European art at the end of the 16th century, its popularity culminating in the 17th century and remaining a prevalent theme today. The concept of vanitas takes its inspiration from the religious text in the Book of Ecclesiastes, which denounces all vanities and material objects as useless in the certainty of death. The reader is advised to cherish existence yet be aware that no one can escape death. Consequently, the promise of eternal life is our only hope in the face of death. The main visual element, that of the skull, is inspired by the danse macabre theme that bears a similar message. Namely, that death is equal for everyone. The vanitas theme can be found in early modern France as well, where a number of artists are inspired by the Dutch and Flemish vanitas paintings and produce such examples. These works can be referred to as French vanitas.

French Vanitas in a European Context

The theme of vanitas, as previously mentioned, is inspired by the Book of Ecclesiastes and is characterized by its dismissal of material things. Life and all existence are transient, with the same applying to all earthly things that can be built during one’s lifetime. Fame, riches, and beauty are all ephemeral and don’t constitute true possessions. We are always under the impression of owning them while, in truth, they escape our grasp. The Ecclesiastes concludes that the only true thing we possess and should invest in is our soul and, consequently, our salvation. Only the promise of the afterlife has the chance of erasing some of the disappointments that material existence offers.

As the source of the theme is rooted in a Christian text, the idea of vanities was well-known and prevalent in the European mentality throughout history. By being such a widespread idea, it was easy for it to become a subject for artists who looked to create artworks with a moralistic spin. This, of course, took different specific shapes in each European region but otherwise followed a common inspiration. Because of this, it is possible to talk about a French or a German vanitas influenced by local socio-political realities and contexts.

The Reformation in France

The Reformation affected all of Europe as it shook the religious foundations of the continent by challenging the practices and authority of the Catholic Church. By hanging up the Ninety-five Theses in 1517, Martin Luther contributed to the start of a period that deeply impacted all areas of European life. The Reformation resulted from division and unrest, as the Catholic Church began condemning Protestantism and all those who followed or spread Martin Luther’s views.

In France, the Reformation didn’t make such an impact at the beginning, and the progress of French Protestants, called Huguenots, was slow. The Reformation in France was fueled by humanists interested in studying the Bible and attaining a purer form of Christianity. The Group of Meaux fueled a more widespread interest in reform, which sparked the desire to study and create theological writings dealing with these problems.

Besides these factors that made Protestantism possible in France, it was only after 1555 that we can talk about an organized effort towards a Protestant Reformation. Despite the slow start, after 1572, the situation developed quite rapidly, leading to a gruesome civil war known as the French Wars of Religion. Such a sad event of the civil war was the Massacre of St. Bartholomew’s Day, where thousands of Huguenots were killed. The war ended when Huguenot Henry of Navarre became king and promulgated in 1598 the Edict of Nantes, which guaranteed religious freedom. However, this didn’t last long as the document was revoked in 1685 by Louis XIV, resulting in the state resuming its persecution against Protestants.

How does French Vanitas Differ from Those of Other Regions?

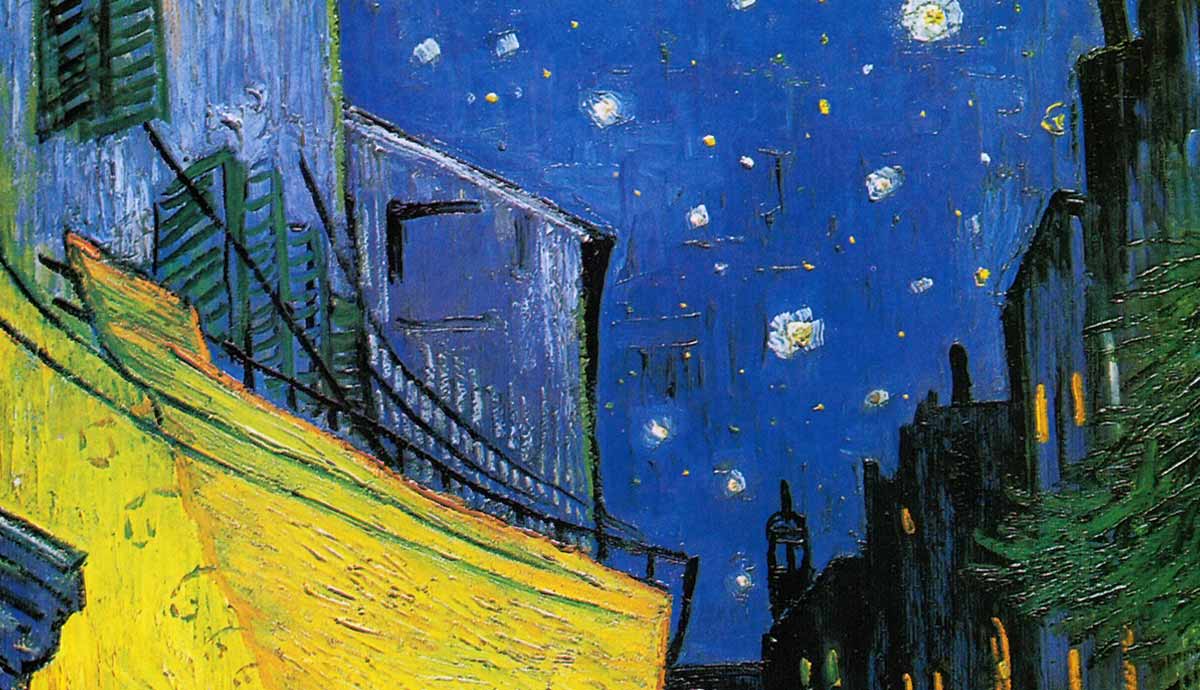

Vanitas with Skull by artist in the French School, manner of Philippe de Champaigne, 17th century, via AnticStore

As previously mentioned, the Reformation had a more complicated path in France, with religious tolerance granted only to be revoked later. With no religious freedom granted after 1685, many Huguenots had no choice but to flee the country, while those that remained had to perform their religious rituals in hiding. They regained their rights only after the French Revolution in 1789. This tumultuous history plays a role in artistic production because artists were restricted or influenced by the political, religious, economic, and social context.

The vanitas theme can be found in two primary types of mainly Baroque paintings in France, making up what is here called French vanitas. The first category follows the Dutch model and incorporates vanitas motifs in a still-life, either directly or indirectly, through the symbolism employed. Dutch still-life paintings are, in most cases, associated more closely with a Protestant perspective that expresses the idea of vanitas using themes related to the Reformation and the religious view it proposed. The second category of French vanitas can be found in historical and mythological paintings, where the vanitas theme is not necessarily the predominant element but can be found in specific parts of the painting which relate back to the ephemerality of material possessions.

How Popular Was Vanitas in France?

French art is more popular for its mythical and historical paintings from this period. The most well-known French paintings are not remembered for their vanitas themes. Moreover, unlike the Dutch Republic and Flanders, still-life painting wasn’t as in demand as other genres. As a result, the vanitas theme is manifested most often in the few still-life paintings, often labeled as being made by a French School or an anonymous artist. Even though their makers are lost in time, most paintings have a generally nice visual quality. They visibly imitate and borrow symbols and elements prevalent in the Dutch and Flemish vanitas still lifes, thus following a European trend.

As in most vanitas paintings, the skull or skeleton is a prevalent motif. This direct representation of death as embodied through a skeleton or parts of it relates to the visual tradition of the danse macabre, which dates back to the Middle Ages. The danse macabre motif was a widespread European artistic representation that carried both a memento mori and vanitas message. It warned against the ephemerality of existence while also advising against attachment to material things. Therefore, the familiarity of this representation in France made the transition towards the theme of vanitas in painting easier, as the basis for this was already present. As it happens for other European regions, the medieval motif aided what we call a “French vanitas.”

Describing Still-life French Vanitas Paintings

Despite the popularity of the danse macabre theme in the Middle Ages, French vanitas was not such a popular genre in painting when compared to its Spanish, Dutch, or Flemish counterparts. Because of this, as well as the political and religious context in France concerning the Reformation, it might be hard to describe what really sets French vanitas apart and makes it uniquely recognizable. As most surviving paintings that fit into this genre are labeled anonymous, it becomes twice as difficult to ascertain whether the painting is even French in origin.

There are two ways of approaching this. The first one is to analyze in detail the objects depicted as they can be a great clue for the origin of the paintings. Vanitas paintings often feature luxurious objects such as fine textiles, jewelry, intricate silverware, and so on. By taking a look at these elegant objects, oftentimes represented in minute detail, one can identify whether they were more common in a specific region. If the painting contains any books with something written on them, then the clue of origin can also be found by deciphering that.

The second way of approaching this is by using more general visual rules, such as the quality of the painting that may indicate the hand of a master or that of a workshop/ minor artist. Most examples of French vanitas paintings also feature the skull quite visibly, so its presence can serve as an extra clue. While the individual elements used in a composition rich in symbolism may appear as common by themselves, they can relate to a specific regional context when decoded together.

The Vanitas Theme Manifested in Other Types of Paintings

Even though this article focuses mainly on vanitas, as seen in still-life paintings, the theme can be found in other genres as well. Such an example is that of historical or mythological paintings, such as the artwork shown above. The example chosen here relates to a strong tradition regarding Mary Magdalene traveling to France, where she died. This legend generated a powerful interest in depicting her figure. Due to this, it comes as no surprise that Philippe de Champaigne, an artist who also painted vanitas still life works, used the same vanitas theme to represent a penitent Mary Magdalene.

Besides this reason, the example was also chosen because it was very common to represent Mary Magdalene as contemplating a skull. The message beyond this representation is the following. Mary realizes that her beauty and youth are ephemeral, and through the skull, she contemplates the only certain and permanent thing: death. The conclusion of her meditation is that she has to repent and focus on her soul and the afterlife. Using a Biblical character and a legendary episode, artists incorporated the entire moral of the Ecclesiastes in Mary’s contemplation of the skull. The lesson behind the vanity of vanities is thus expressed visually in a narrative and less symbolic way, as opposed to the still-life paintings that are so well-known for using this theme.

Some Important Characteristics of French Vanitas

As mentioned before, French vanitas paintings, whether depicted in still-life, historical, or mythological genres, share the commonality of featuring a skull. The skull or parts of a skeleton are the prime symbols of death as they represent the remnants of the human body after it no longer exists as a living being. Following the example of the Dutch, books, flowers, and fruits are the next most common element in the French vanitas.

Organic things like fruits and flowers that are either in full bloom or decay make up an indirect way of indicating the impermanence of human existence. Like all organic things in this world, the human also blooms and fades away, leaving nothing behind.

Meanwhile, books stand for human activity, for things only humans do and enjoy. Even though books and writing can be left behind, the knowledge of one person dies together with them and disappears from this world. The same goes for any other art or skill. Humans train to exceed into something for most of their life, but then this effort and achievements are meaningless in the face of death.

The same idea can be applied to riches and all sorts of luxury objects such as art. In the above anonymous painting, a hint of its French origin can be found in the sketch that is painted. The drawing seems to be either a copy or a preparation drawing for a painting with a mythological theme, as two nude god-like figures seem to be in a struggle. As historical and mythological themes were more prevalent in countries with a Catholic majority where the Counter-Reformation manifested more notably, it is safe to assume that the French attribution is indeed correct.

In conclusion, the genre of vanitas is manifested in the early modern period in France as well, following a European trend that takes its inspiration from both The Book of Ecclesiastes and the medieval motif of danse macabre. Therefore, one can talk about French vanitas as the artworks produced in the French region which have specific characteristics that distinguish them from other works.