Berthe Morisot was an outstanding Impressionist, admired by her male colleagues such as Degas and Renoir. As a woman of her time, she was severely limited in spaces and situations she could depict but managed to get the best of what was available to her. She was particularly close to Edouard Manet and even married his younger brother. Read on to learn more about Berthe Morisot, the outstanding Impressionist.

1. Berthe Morisot Had Artistic Ancestors

Berthe Morisot was born in 1841 into an affluent family of a high-ranking civil servant and was one of the four Morisot siblings. Like her older sister Edma, she demonstrated a keen interest in art. Traditionally, in such families, girls’ curriculums included arts as a respectable hobby. However, Morisot’s parents decided to put more effort into following their daughters’ passions. Perhaps, the interest in art ran in the family: Morisot’s mother was a great-niece of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, one of the most famous painters of the Rococo era. Fragonard was the exemplary artist of his time, loved for his frivolous subjects and pastel color palette.

2. The Morisot Sisters Were Trained Artists

Supported by their family, the Morisot sisters received a serious artistic education that many male artists could only dream of. Both Edma and Berthe studied at the studio of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, the famous painter of the Barbizon School. Formal training in art academies was unavailable to them, so they resorted to the help of private tutors. Accompanied by professional artists, they visited the Louvre to copy paintings from its collection.

Both sisters’ talents were recognized by their tutors, and both had their chances to succeed in professional careers. Unfortunately, Edma had to seize her painting practice after marrying a naval officer who was a friend of Edouard Manet. Family life and expectations from a married woman did not work out well with artistic ambitions. In 1869, Berthe Morisot painted a portrait of her sister that was filled with gentle sadness. There, Edma sat near an open window but barely looked at the world outside. At the time, she just found out she was pregnant and, according to a tradition of her time, moved back to her mother’s home to be cared for. Edma’s face revealed boredom and sadness, possibly related to her radical change of life circumstances.

3. She Worked With Edouard Manet and Inspired Claude Monet

Berthe Morisot met Edouard Manet in 1868 when she was a promising student of Camille Corot. Initially, she entered his studio to study, yet Manet soon realized Morisot was much more knowledgeable and talented than he expected. In the years that followed, Manet painted eleven portraits of Morisot. Not a single one of them depicted her as an art student. This was a striking contrast to the portrait of another student of Manet, painter Eva Gonzales.

He painted Gonzales in a manner similar to the 18th-century society portrait of a lady with a charming hobby: her dress was inappropriately lavish for working at an easel, and the position of her hands and back were in no way practical for a practicing artist. The portraits of Morisot, however, never showed her painting, focusing on her as a person. Clearly an intelligent and respected person, in her portraits, she was most frequently dressed either in classy total black or white ensembles.

The nature of the two artists’ relationship led some art historians to believe that there was some romantic tension between them, possibly unresolved. However, others insist that Manet valued Berthe Morisot as a smart and talented artist. We know that Morisot convinced Manet to try painting outside of his studio. His first plein air work was painted in Morisot’s garden, launching a practice shared by many other Impressionists. Morisot’s influence on the Impressionist scene is hard to underestimate. Some art historians believe she launched Claude Monet’s famous series of water lilies paintings. Monet bought a now-lost painting by Morisot featuring a pond covered in blooming lilies and soon started to produce his own work with the same subject matter.

4. Manet Ruined One of Her Paintings

However, the relationship between Morisot and Manet was almost ruined one day when he allowed himself to interfere with one of her works. In 1870, Morisot was painting a portrait of her mother and sister and was quite unsure of the result. She intended to ask Manet for advice, but before she even finished her story, he took a brush and started repainting the work. Initially, he started with a few small details in the lower half of the image but soon overpainted the entire portrait, turning it into a caricature, in Morisot’s words.

Morisot was devastated. Not only did Manet ruin her work, but he also destroyed her chances at exhibiting the painting at the Salon that year. Morisot prepared the work specifically for the event. The Salon’s rules stated it would not accept a painting created by more than one artist.

5. Her Gender Limited Her Choice of Scenes

As a woman artist in the 19th century, Morisot still faced many restrictions despite the support of her family and male colleagues. Although she encouraged Manet to paint outside, her own possibilities for that were severely limited. As a woman of considerable social status, she could not appear unaccompanied in public spaces. One of her most famous works, the portrait of her sister Edma at the seashore, was most likely discreetly sketched during their walk and later finished in the privacy of the sisters’ studio.

As in the case of the famous portrait of her pregnant sister, open windows and home environments were frequent occurrences in Morisot’s paintings. These windows offered a glimpse into a larger world that was almost unavailable to them. While the men of the movement explored bars, dance halls, and city streets, for a woman artist, such pursuits were an unaffordable luxury. Morisot’s social status left her no chance to explore such spaces without causing a scandal that would destroy the reputation of not only herself but her entire family.

6. She Married Edouard Manet’s Brother

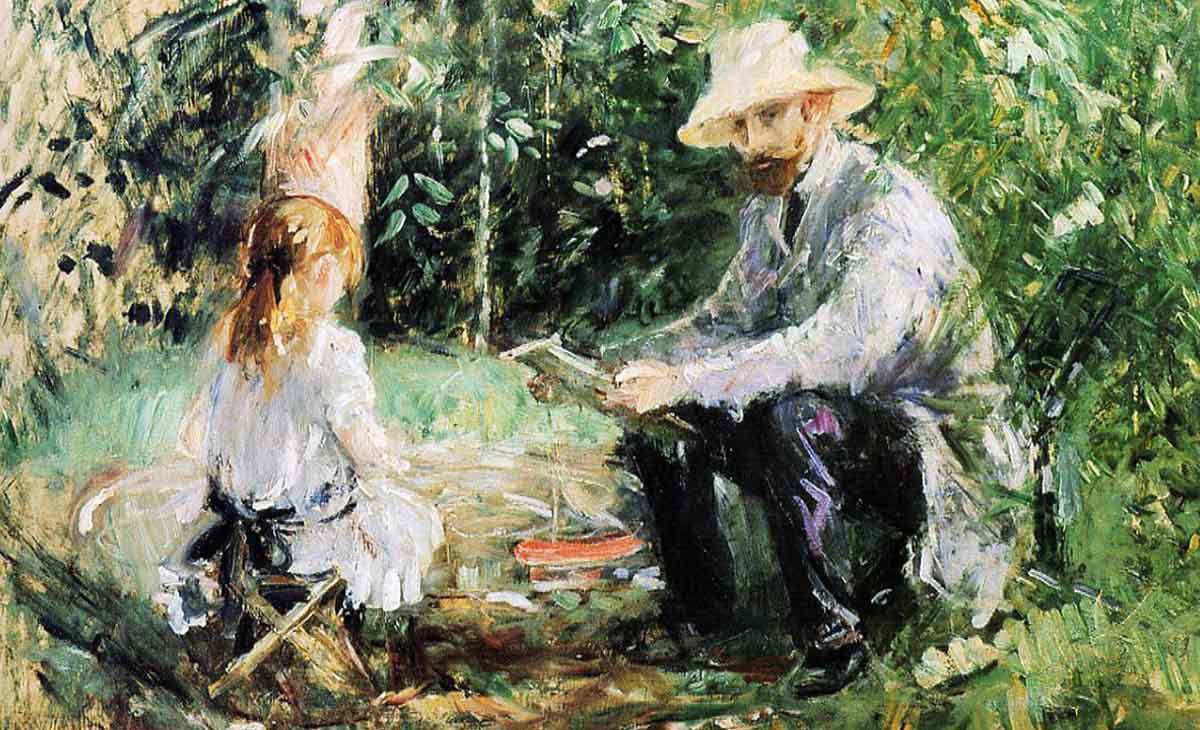

For a woman of Morisot’s time and social status, marriage was almost inevitable. However, she was lucky enough to marry a fellow artist who understood her talent and was ready to supply her with the space and time needed to continue her artistic practice. Morisot’s husband was the younger brother of Edouard Manet Eugene. Eugene was also a painter, although less skilled and innovative than his brother. After the marriage, he devoted most of his efforts to promoting his wife’s career.

In 1878, Berthe Morisot gave birth to her daughter Julie Manet. Julie was one of Morisot’s favorite models, and she also posed for her friends like Renoir and Degas. Unfortunately, she lost both her parents by the age of 16 and grew up in a friend’s family. Today, Julie Manet is known as a biographer and the author of the book Growing Up with The Impressionists.

7. She Had a Commercially Successful Career

Even Edgar Degas, who was known for his misogyny and rejection of women’s artistic ambitions, recognized Morisot’s talent and stated he was proud to have such a skilled artist among his fellow painters. Apart from her colleagues’ praise, Morisot enjoyed the well-deserved monetary appreciation of her work. Berthe missed only one annual exhibition of the Impressionists, and she had a legitimate reason for that—she was pregnant with her daughter. She successfully sold her paintings during exhibitions and exhibited at almost every major art show of her time. Critics and collectors held her work in high regard, although unable to let go of the stereotypes, highlighting the feminine qualities of her painting, such as delicate brushwork and soft colors.

8. Berthe Morisot’s Daughter Saved Her Mother’s Legacy

Berthe Morisot died in 1895 from viral pneumonia, which she contracted while treating her daughter for the same illness. A year after her death, at the age of 54, her friends and colleagues arranged a retrospective of her work. Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and the famous Symbolist poet Stephane Mallarme curated and arranged the collection of more than 400 paintings and sculptures.

Degas insisted on a diverse display of works and wanted to mix Morisot’s paintings with drawings that he admired. Renoir, however, chose a more traditional way of exhibition design at the time, separating mediums and placing a bench in the middle of a room with paintings. Julie Manet, who was seventeen at the time, had the important task of putting on the wall labels. In her diary, she kept notes about almost every work present at the show. Later, this diary became the basis for the catalogue raisonné of Berthe Morisot’s work.