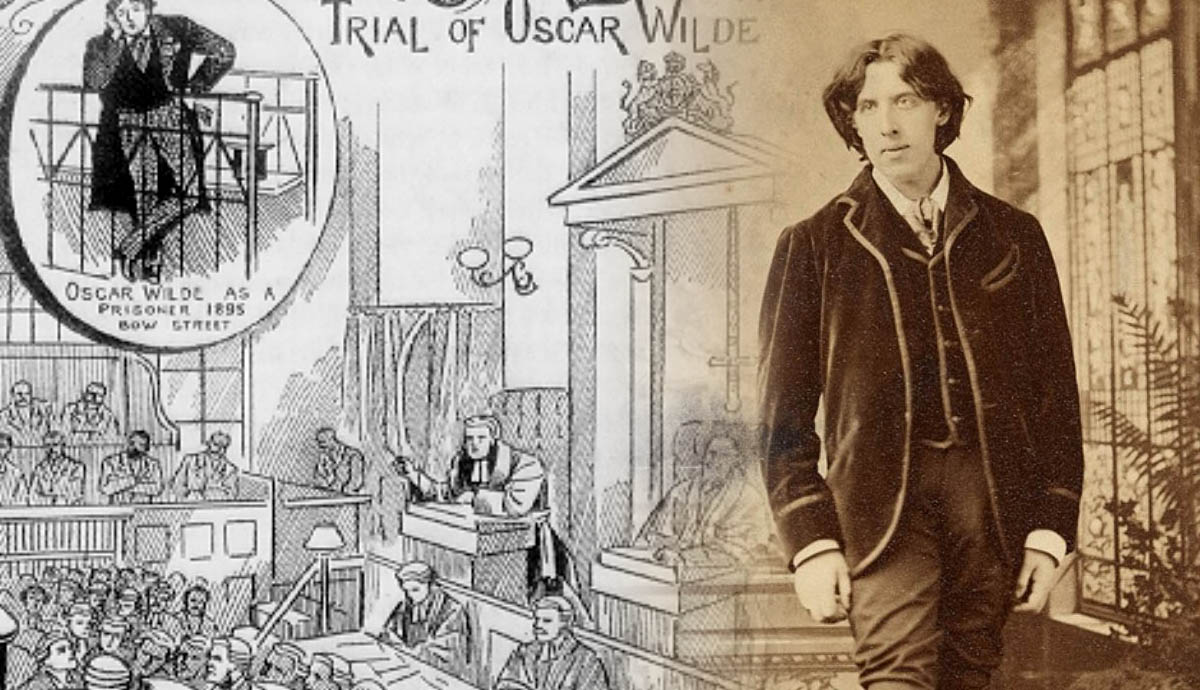

Oscar Wilde was known as the father of the aesthetic movement and for works such as The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Earnest. He was also involved in a celebrity scandal that filled the newspapers of Victorian Britain. Wilde was the author of his own downfall when he launched a criminal libel case against an aristocrat who accused him of committing indecent acts with his son. The tables were turned on Wilde when he found himself under arrest, and he was ruined when he could not clear his name.

1. Oscar Wilde Was On the Prosecution Side In the First Trial

Oscar Wilde’s first trial took place at the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, also known as the Old Bailey, on April 3, 1895. Wilde’s legal troubles began four years earlier when, at the age of 38, he met 22-year-old Lord Alfred Douglas, a student at Oxford. Wilde was by then a well-known literary figure and leader of the aesthetic movement, which believed in “art for art’s sake.” Wilde and Douglas often dined together, stayed in houses and hotels together, and Douglas was the recipient of several gifts from Wilde; Wilde even wrote a sonnet about Douglas.

While still a student at Oxford, Douglas gave an old suit to a more impoverished friend, Alfred Wood. In a pocket of the suit, Wood discovered compromising letters which Wood then used to blackmail Wilde for the (back then) not insignificant sum of £35. Two other blackmailers received smaller sums of money for the return of the remaining letters.

Wilde’s troubles truly began not as a result of this attempted blackmail but by the actions of Lord Alfred Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry. Concerned about his son’s relationship with Wilde, by early 1894, Queensberry had threatened to disown his son if his relationship with Wilde continued. Queensberry also turned up at Wilde’s house with a prize-fighter. He even warned hotel and restaurant managers that they would be beaten if he ever discovered Wilde and his son on their premises.

On February 14, 1895, Wilde’s latest play, The Importance of Being Earnest, was due to open in London. Queensberry intended to disrupt the performance and address the audience about Wilde’s decadent lifestyle. When he found out about this, Wilde arranged to have the theater surrounded by police. Four days later, Queensberry left a card at Wilde’s social club with a message saying: “To Oscar Wilde posing as somdomite [sic].” When Wilde received the card two weeks later, he decided to seek criminal prosecution against Queensberry for libel. Wilde assured his attorney, Sir Edward Clarke, that he was innocent of any such charges. Unconcerned about the trial, Wilde left his attorney’s office to go on a short trip with Douglas to the south of France before the criminal proceedings began.

2. Wilde’s Attempt to Sue Queensberry Resulted In a Warrant For Wilde’s Arrest

Prior to the libel trial, friends of Wilde’s, including the playwright George Bernard Shaw and Frank Harris, tried to persuade Wilde to drop the case. They even encouraged him to leave the country to continue his writing in France, where attitudes towards homosexuality were more tolerant. Wilde refused to do so. Oscar Wilde’s first appearance at the Old Bailey occurred on April 3, 1895, when he testified against Queensberry for calling him a “sodomite.”

In the prosecution’s opening statement, Wilde’s attorney, Clarke, attempted to explain away a letter Wilde had written to Douglas. The letter contained phrases such as “red rose-leaf lips of yours,” “madness of kisses,” and “your slim gilt soul.” Clarke explained that the words “may appear extravagant to those in the habit of writing commercial correspondence … but Mr. Wilde is a poet … and is prepared to produce anywhere as the expression of true poetic feeling.” When Wilde took the stand, he declared that there was no truth in any of Queensberry’s accusations.

After lunch, Queensberry’s attorney Edward Carson, who had been a rival of Wilde’s since they were at Trinity College Dublin together, cross-examined Wilde. His cross-examination focused on Wilde’s written words as well as his actions. The literary part included references to Wilde’s own letters and his aesthetic movement works The Picture of Dorian Gray and Phrases and Philosophies for Use of the Young. Wilde remained somewhat flippant on the stand: when reminded that The Picture of Dorian Gray contained the sentiment that “There is no such thing as an immoral work … books are well written or badly written,” Wilde declared that Dorian Gray could only be considered a perverted book by “brutes and illiterates. The views of Philistines on art are incalculably stupid.”

However, Wilde became more uncomfortable when Carson started to ask him about his personal relationships. The jury was shown a number of gifts that Wilde had given to young men. Carson told the court that some of the recipients were not “intellectual treats” but newspaper sellers, valets, and even barely literate unemployed young men. When Carson asked Wilde if he had kissed a young man who was just sixteen years old at the time, Wilde replied, “Oh, dear no! He was a peculiarly plain boy.” Wilde was unable to answer Carson’s further questions demanding to know if the only reason Wilde hadn’t kissed him was that he was ugly. Carson queried why Wilde had mentioned that at all.

To the surprise of many, the prosecution closed its case without calling Lord Alfred Douglas as a witness. In his opening speech in defense of Queensberry, Carson announced that he would call to the witness box several young men known to Wilde. Clarke knew then that not only was his libel case lost, but that Wilde was in danger of being prosecuted himself.

After that day’s trial, Clarke met with Wilde to explain that it would be almost impossible for a jury to convict a father who was “endeavoring to save his son from what he believed to be an evil companionship.” Wilde agreed to withdraw the prosecution and agree to a verdict of the charge of “posing.” However, despite the withdrawal of the libel prosecution, Queensberry’s attorney had forwarded to the Director of Public Prosecutions copies of statements made by the young men they had planned to produce as witnesses. By mid-afternoon, an inspector from Scotland Yard had appeared before a magistrate to request a warrant for the arrest of Oscar Wilde.

3. The First Criminal Trial Against the Leader of the Aesthetic Movement Led to a Hung Jury

Oscar Wilde was not given bail (despite being charged with a misdemeanor rather than a felony) and spent three weeks in Holloway jail before appearing at the first of his criminal cases on April 26. As a defendant, Wilde was tried alongside Alfred Taylor, who was charged with procuring young men for Wilde. Wilde and Taylor faced 25 counts of gross indecencies and conspiracy to commit gross indecencies. Several young men testified to the prosecution about their involvement in helping Wilde act out his sexual fantasies. In the courtroom, these young men expressed shame and remorse about their own actions.

Wilde took the stand on the fourth day of this trial. Gone was the haughtiness of the first trial; instead, he answered questions quietly and denied all allegations of indecent behavior. Like the leader of the aesthetic movement that he was, Wilde stated that: “It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

Clarke’s closing speech on behalf of Wilde implored the jury to both clear Wilde and “clear society from a stain.” The jury deliberated for three hours before deciding that it could not reach a verdict on most of the charges. On May 7, Wilde was released on bail and enjoyed three weeks of freedom before his next trial.

4. The British Government Seemed Intent On Prosecuting Wilde

Oscar Wilde’s second trial began on May 20. This time, the British Liberal Government seemed determined to secure a conviction against Wilde. The Prime Minister, the Earl of Rosebery, was himself suspected of having had a homosexual affair when he was the Foreign Minister with no less than Francis Douglas, another of Queensberry’s sons. Francis Douglas was killed in a hunting accident (widely believed to be suicide). There is plausible evidence that Rosebery himself would be threatened with exposure by Queensberry if he failed to prosecute Wilde.

This second prosecution was led by England’s top prosecutor, Solicitor-General Frank Lockwood. While this trial was similar to the first, the prosecution failed to call its weakest witnesses and instead focused on the stronger ones. In both trials against Wilde, in addition to several young men (some of whom were known to be extortionists themselves), landladies, neighbors, housekeepers, hotel staff, and even a male masseur were called to the witness box. Besides Charles Parker and Alfred Wood, known to be sexual blackmailers in their twenties, no other witnesses testified that they had caught any individual linked with Wilde in flagrante delicto. Nevertheless, the evidence against Wilde was seen as compelling.

In his closing statement for the defense, Clarke denounced Parker and Wood as having secured immunity for their own past “rogueries and indecencies” by testifying on behalf of the Crown. Clarke also declared before the court that the pair were blackmailers. Clarke implored the jury to acquit the leader of the aesthetic movement. Clarke believed that this “distinguished man of letters” could “give in the maturity of his genius gifts to our literature.” Solicitor-General Lockwood spoke the final words of the trial. This time, after more than three hours of deliberation, the jury found Wilde guilty on all counts but one.

5. The Final Verdict Against Oscar Wilde Changed How British Society Viewed Homosexuals

Oscar Wilde and Alfred Taylor were both sentenced to the maximum sentence – two years of hard labor. Wilde spent the last eighteen months of his imprisonment at Reading Gaol, where he wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol. This final work did not reflect the aesthetic movement. On his release from prison, he sailed to Dieppe, France, and never returned to England again. Suffering from ill health throughout his exile, he died in France just over three years later.

Before Wilde’s trials took place, public attitudes showed a level of pity for those who engaged in same-sex relationships. After the trials, homosexuals were seen more as predators and as a threat. These trials also caused the public to associate art with homoeroticism, and that effeminacy was an indicator of homosexuality. People began to grow suspicious of any male relationships that exhibited a degree of intimacy. Those involved in close same-sex relationships became concerned that anything they might do might suggest impropriety.

Before Wilde’s trials, prosecutions for consensual homosexuality in Victorian England were about as rare as they were in the United States at the end of the 19th century. As Solicitor-General Lockwood stated in his closing argument, “[Wilde] is a man of culture and literary tastes, and I submit that his associates ought to have been his equals and not these illiterate boys whom you have heard in the witness-box….”

Lord Alfred Douglas never testified at any of Wilde’s trials. It is surmised that had Wilde chosen men from his own social circle instead of young prostitutes and blackmailers, he may never have found himself on trial at the Old Bailey. Not until 1967 was consensual homosexuality decriminalized in England. In 2017, Oscar Wilde was pardoned, along with approximately 50,000 other men, for homosexual acts that were no longer considered offenses.