There are stories that we could recite by heart, stories that accompanied us during our childhood and made us sing and dream. One of these is certainly Beauty and the Beast, an animated fantasy movie released by Walt Disney in 1991. The plot recounts the emergence of a love story between a prince, who has been transformed into a Beast, and a young village lady, Belle, whom he imprisons in his castle. But what does this story have to do with the history of colonialism, the

collecting of world wonders, and the 20th-century practice of freak shows?

The Early Court Freak Shows

As the movie soundtrack reveals, this is a tale as old as time, but, as this article will show, not really one as true as it can be. The tale behind the tale is in fact a much harder one to take in. It tells a story about colonial subjugation, prejudice, and discrimination over physical differences. This is the story of Petrus Gonsalvus, of his family, as well as of those who, just like them, were turned into objects of wonder or entertainment by a discriminatory and exploitative ruling class.

The Beast of this story is Pedro González, born in 1537 in Tenerife, Canary Islands. He was stolen from his hometown when he was a ten-year-old boy in order to be brought to Europe to the court of the newly-crowned King of France Henry II. Petrus was offered as an exotic gift, brought to Europe within an iron cage that by itself reveals how the 16th-century Europeans perceived him: not as a human being, but as a wild creature to be observed, studied, and even tamed. He, indeed, was characterized by a rare feature that, at his first appearance at court, made everyone gasp: he was fully covered by an excessive amount of bodily hair.

The immediate reaction of early moderns was to draw an immediate connection between Petrus’s bodily appearance and bestiality, which derived from the same cultural notions that had led to his very capture in the first place. At a time when colonial expansion had begun, new territories had been mapped, and new trade routes traced, not only did Europeans explore and settle on other areas of the world, but they also conquered and exploited them, capturing and enslaving the local population and confiscating their land and resources. This phenomenon engendered and progressively reinforced ideas about racial, cultural, and institutional superiority according to which white Europeans, who considered themselves culturally, educationally, and

religiously superior, were entitled to continue their expansionist and exploitative agenda.

Indeed, once Pedro was offered as a gift to Henry II, the king immediately set out to turn what he saw as a wild man into a well-educated gentleman, in a civilizing effort that well describes the unquestioned early modern belief in the inferiority of those that displayed features of Otherness. The king renamed the boy Petrus Gonsalvus, using a Latin version of his name in an effort to eradicate his origins and identity. Petrus was made to wear noble clothes and he proved highly receptive to the numerous lessons in Western etiquette, reading, and writing. He became fluent in three languages and gained an honorable place at the king’s court.

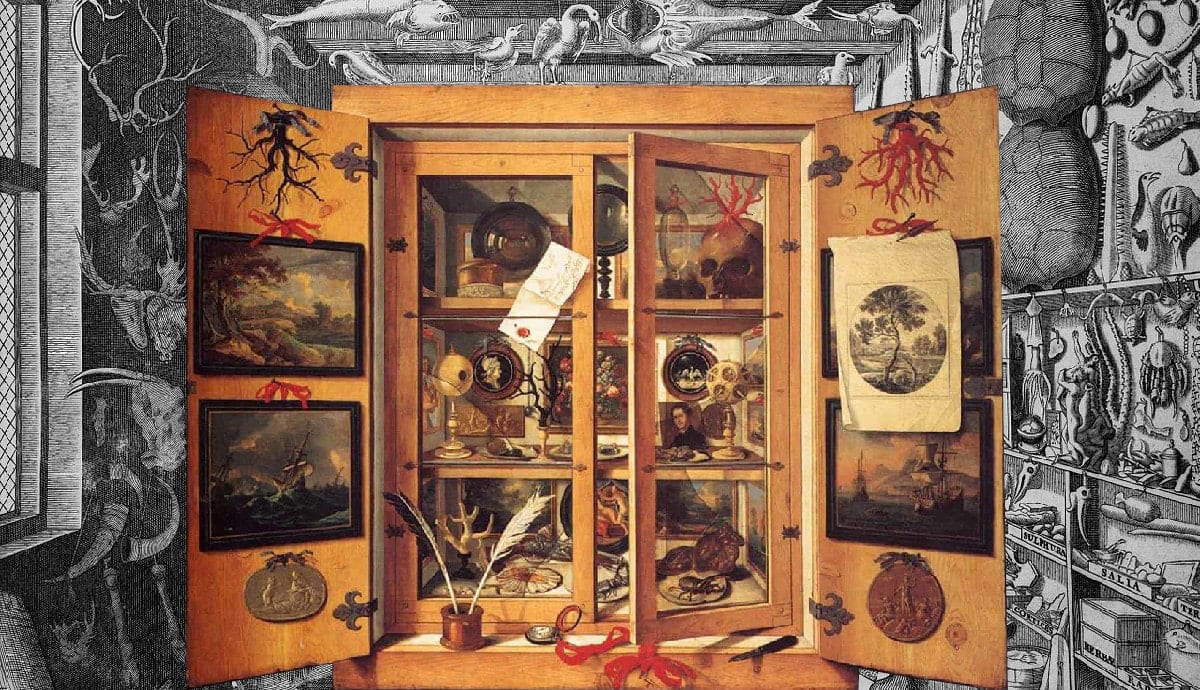

It is not to be forgotten, though, that this story does not have a happily ever after, and Petrus, after all, was always going to remain a mere object of wonder and curiosity, brought into a culture that claimed ownership over the whole world. This was also the time when naturalia and artificialia from the New World were brought together in the emerging Cabinets of Curiosities. These were eclectic rooms born across Europe that contained collections of bizarre natural objects or complex man-made artifacts, often thought of as curious because of their distant origin. These rooms aimed to bring the entire world into a single space.

This collecting rationale, however, also encompassed the bodies of those who were perceived as being different, hence curious. Jan van Kessel’s Allegory of Africa makes this clear. In a space dedicated to displaying various objects, among which paintings of natural wonders, exotic animals, and hand-made tools can be found, two African figures dressed in ethnic clothes, are also offered to the gaze are offered to the gaze of their European audience.

Anything that was perceived as Other was exploited as a source of wonder and entertainment in early modern culture. As a painting by Giacomo Vighi attests, a common presence in courts was that of individuals suffering from restricted growth. Dwarves were literally collected by nobles and royals because of their stature and bodily features, with 93 of them being recorded at the court of Tsar Peter I (1682-1725) and 70 at the Spanish Royal Court between 1563 and 1700.

Petrus Gonsalvus fit both of these categories. He was seen as exotic and he was physically non-normative. Henry II’s wife, Catherine de Medici, knew this too well and, in fact, she did not hesitate to exploit Petrus as a source of courtly entertainment as soon as her husband died. Foreseeing the possibility of gaining further value from the equally wondrous and rare offspring Petrus was likely to beget, Catherine sought a wife for him, choosing the daughter of a servant also named Catherine, with the intent of experimenting with what would happen once her beauty was matched with someone who looked like a beast.

Hypertrichosis: the Apogee of Discrimination

Love, as one can by now predict, did not free our protagonist from captivity, nor did it transform his hairy appearance, as it happens in the Disney movie. Petrus, in fact, was not the victim of a spell but rather suffered from an extremely rare and incurable genetic disorder known by now as hypertrichosis. This condition caused him and some of his seven children who inherited the disease, to have hair growing all over their bodies. When Petrus and Catherine had their first hairy child, Catherine de Medici was thrilled to see her experiment accomplished. She succeeded in creating a wild family out of her own design.

One of Petrus’s children was depicted by Lavinia Fontana in a delicate and tender portrait that manages to represent the smooth skin of the child, despite the presence of hair all over it. Nonetheless, the letter the child holds is a tough reminder of her and her father’s unchangeable destiny: Don Pietro, a wild man discovered in the Canary Islands, was conveyed to his most serene highness Henry the king of France, and from there came to his Excellency the Duke of Parma. From whom [came] I, Antonietta.

Once again, Antonietta’s and her family’s origins are equated to the wilderness, while the King of France is praised for his civilizing effort. Despite their noble upbringing, the Gonsalvus continued to be admired for their bestiality across Europe, being forced to tour other princely courts. Ulisse Aldrovandi, one of the physicians who examined them during these tours, defined Petrus as the man of the woods, and indexed Antonietta in his book Monstrorum Historia (the History of Monsters), making clear that the family was never to be considered truly human.

The 20th Century Freak Show

Far from remaining an isolated early modern phenomenon, the association of the disease (also called the werewolf syndrome), with bestiality protracted itself until well into the 20th century when the so-called Freak Shows were still touring Europe and America. These entertainment enterprises, which had been at their peak of success since the 19th century, exhibited biological rarities spanning from non-white such as men and women who suffered from disabilities or malformations, which the shows exploited for profit and referred to as monstrosities, marvels, or freaks of nature, marketing them as must-see undiscovered human beings.

Among the bodily oddities on display, spanning from uncommonly large or small humans to those with intersex variations, or those with extraordinary physical or mental conditions, subjects with hypertrichosis were often presented to the public as hybrids between humans and animals. Several cases have been recorded throughout history, some of the most documented ones being that of Alice Elizabeth Doherty who was born in 1887 in Minneapolis, fully covered by two-inch long, silky blond hair since birth, and that of Fedor Jeftichew, born in 1868 in St. Petersburg.

Doherty was made to begin her exhibition career at the age of two. By the age of five, she was brought across the Midwest by her family, becoming widely known under the nickname of Minnesota Woolly Girl. Even more blatantly discriminatory was the nickname given to Fedor Jeftichew who appeared with his father, suffering from the same genetic disorder, on a poster made in 1874 for a show on their European tour as Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy.

Even more explicitly, another poster dating back to 1846 presents a man with the same syndrome and outspokenly states that one can hardly decide whether this creature is a human or a beast. What is it? the poster asks in relation to the man depicted in the middle, his body fully covered in thick, dark hair. Is it an Animal? Is it Human? the poster insists. Is it an extraordinary FREAK of NATURE, or is it a Legitimate Member of Nature’s Work? it carries on, insinuating that his condition and his humanity are mutually exclusive characteristics.

Petrus Gonsalvus is therefore at the start of a genealogy of discrimination against, and exploitation of those perceived to have non-normative bodies and deemed undeserving of being classified and treated as humans. These are stories of subjugation and oppression, in which bodily differences become synonymous with inferiority and bestiality. Once seen in light of this genealogy, in fact, the Disney movie appears as a sanitized version of Petrus’s story in which, if one thinks about it, the reminiscences of prejudice and the now-unspoken questions over what makes one human are still implied.

In the Disney tale, the bodily difference is still presented as something that instills fear and fascination. It’s something that needs to be tamed, domesticated, and embellished according to a specific canon of beauty. Despite Belle’s progressive recognition of the Beast’s kind nature and despite her unconditional love for him, the Beast’s humanity is only unlocked and verified when he is eventually magically transformed into a good-looking, white, and hairless man.