Georges Bataille’s life, or as much as we know about it, does not broadly reflect the extreme and transgressive character of his writing. Having trained as an archivist, Bataille spent much of his life working at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. He also wrote literary reviews, while producing his own body of work gradually, mostly between 1928 and his death in 1962. Initially publishing the fictional works Story of the Eye and Madame Edwarda under pseudonyms (Lord Auch and Pierre Angélique respectively), Bataille sought to distance his transgressive, explicit, even pornographic writing from his essentially respectable bourgeois existence.

Georges Bataille’s Life and Relationships

Beyond these facts of Bataille’s ordinary if prolific academic life, we know of two marriages and an affair – a similarly shockless record for the writer of scandalous erotic tracts. Bataille’s first marriage, to Syliva Maklès, an actress he met in Paris, ended with separation some eight years later. After her split with Bataille, Maklès commenced a relationship with Bataille’s friend and fellow-traveler in the analysis of eroticism, Jacques Lacan.

Perhaps appropriately, Bataille’s fascination with transgression and extremity was not merely an apology for scandal in his personal life, and where it touched his life – and it is hard to imagine, reading Story of The Eye, that it would not have – no record escapes (save perhaps the rumors of his desire to be sacrificed by a member of Acéphale). As Bataille stresses in so many of his theoretical works, his concern is not with events on the scale of the individual subject, but on a general one. Perhaps our look at him should mirror that position.

Marxism, Sadism, Surrealism

Bataille’s writings are a latticework of diverse intellectual influences, ranging between media, genres, disciplines and periods. Psychoanalysis, surrealism, Marxism, and mysticism all play central roles throughout Bataille’s thought, albeit frequently in altered guises, transformed and amalgamated with one another. Bataille’s literary output vividly captures the intensity and excess he advocates for in much of his philosophical work.

His early novella, now amongst his most renowned works, Story of the Eye, captures Bataille’s long-lived fascination with the Marquis de Sade, libertinism, and erotic writing. The text follows its narrator and his companion, the ‘heroine’, Simone through abstract passages and barely sketched settings, describing in vivid detail escalating combinations of sex, excrement, and violence. The book points towards many of the ideas later developed in Erotism (1957) in its melding of erotic extremity with a distinctly religious reverence: a marriage of extremes which defines both the structure and content of many of his works. The novella is also distinctly surrealist in style, set in barely sketched spaces with characters suddenly – sometimes almost magically – appearing to join set pieces of sexual transgression.

While Bataille’s relationship with André Breton went sour soon after their first meeting, the influence of Breton and his fellow surrealists (above all the explicit Freudianism of much surrealist painting, its attentiveness to the simmering eroticism of the unconscious) is felt strongly in Bataille’s fiction. More fundamental still to Bataille’s philosophy is Surrealism’s celebration of irrationality.

While Bataille would eventually, in the closing pages of The Accursed Share, lay out the groundwork for a new rationality to better (less destructively) regulate the consumption of surplus wealth, the path to this conclusion is shaped by the rejection of rationality (in its economic, rather than philosophical, sense). Bataille’s fascination with the irrational shares with the surrealists its underlying belief in a field of consideration which extends beyond the personal, conscious, and human into the collective, unconscious, and ecological, and where the rationality generated by, and appropriate to, the former no longer holds.

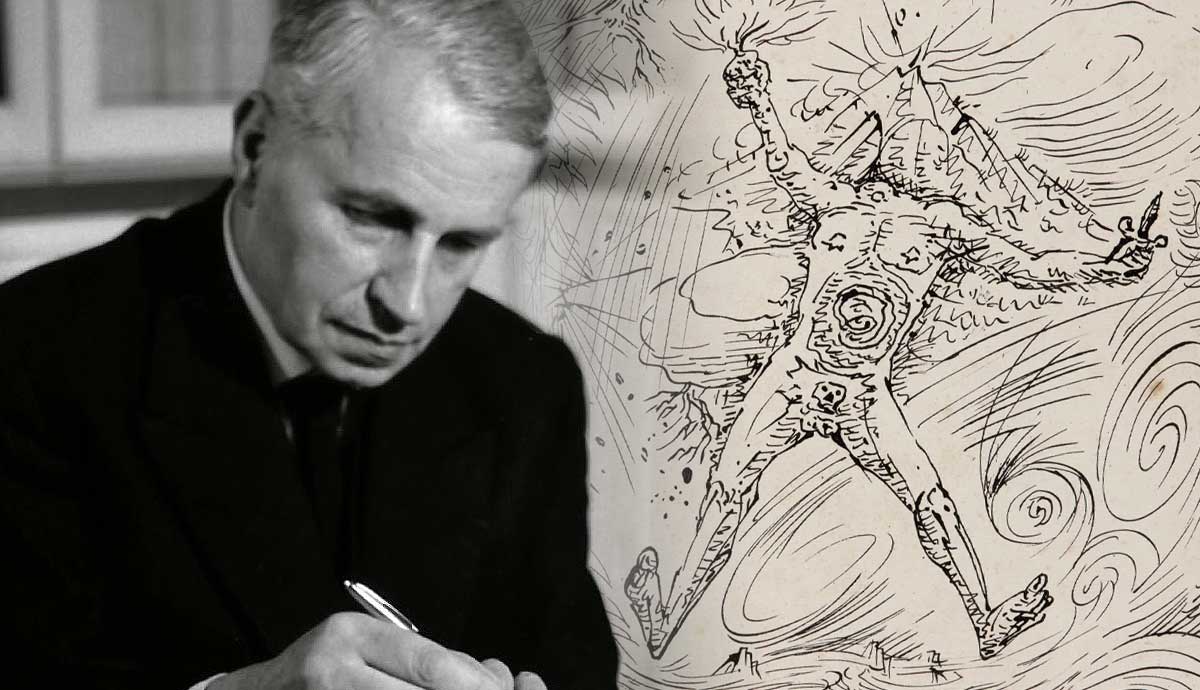

Founder of the literary reviews Critique and Acéphale (also the name of Bataille’s secret sacrificial society), Bataille also promoted and tangled with the writing of fellow philosophers of eros and excess, psychoanalysts, and surrealists. Among them were Jacques Lacan, André Masson, and Pierre Klossowski. In these figures and their strands of thought – as in Marx, Sade, and Nietzsche – Bataille found celebrations and outlets of destructive and divine excess: rituals, sex, and death that merge together and dissolve individual subjects into one another.

Bataille marshals the very different characters of the psychoanalytic and surrealist unconscious, Marx’s proletariat, Sade’s amoral libertine, and Nietzsche’s God-like Übermensch into a single, expansive philosophy, which aims at the destruction of the petty boundaries of human subjectivity, and that subjectivity’s politics, religion, and thinking.

The separateness of individual human subjects finds its simplest expression in Bataille’s work with the term ‘sovereignty’, and the centrality of anti-sovereignty to Bataille’s philosophy could not be more clearly stated than in the final words of The Accursed Share: ‘The main thing is always the same: sovereignty is NOTHING.’ (The Accursed Share, Volume 3, 1949)

Excess, Expenditure, and the Sun

An illustrative example, both of Bataille’s philosophical method and of his most persistent interests, is the treatment of the role of the sun in many of his texts. Bataille writes at length about the sun, its place in the history of philosophy, its religious and ritual significance, and above all its careless expenditure of energy. The sun in Bataille precedes humanity, reason, and subjectivity. In Bataille’s estimation ‘we are ultimately nothing but an effect of the sun’, and much of his work suggests thinking in terms of ‘solar economy’ rather than human self-interest (Bataille, Œuvres Complètes, 1970; VII 10) .

While the economic theorization of human and natural activity occurs most completely in the multiple volumes of The Accursed Share (1949), the themes of excess and expenditure permeate Bataille’s writing. The sun, whose radiation ‘loses itself without reckoning, without counterpart’ becomes a model for the wanton expenditure of energy, which for Bataille finds perhaps in ultimate expression in Eroticism. (Œuvres Complètes, 1970; VII 10)

Much of Bataille’s thought opposes itself to the specters of taboo, usefulness, and stinginess, categories with all manner of philosophical and political connotations. The explicit political and economic connotations unpicked in The Accursed Share find many of their theological and philosophical counterparts in Erotism (1957), and their literary-erotic ones in Story of the Eye (1928). This parallelism is important throughout Bataille’s work, in which themes are frequently revisited under different guises, and tied together with shared metaphors and representations. Thus, the sun is the emblematic meeting points of libertine erotic excess, anti-capitalist political economy, and Bataille’s favorite wastefulness of all: death.

The reconfiguration of the sun as symbol and embodiment of death is typical of Bataille’s iconoclastic, but frequently oblique, relation to the history of philosophy. The sun undergoes a transformation from metaphysical truth in Plato’s Republic, to the emphatically material site of death in Bataille’s philosophy. Bataille goes on, in typically scatological fashion, to underline this re-casting of the sun with references that explicitly sully its apparent purity and lucidity:

“The fecal eye of the sun is also torn from its volcanic entrails and the pain of a man who tears out his own eyes with his fingers is no more absurd than that anal setting of the sun.”

Œuvres Complètes, II 28

The sun is no longer merely its illumination, the light of truth, but an eye, and a “fecal” eye at that. Bataille corporealizes philosophy and finds at the heart of our most apparently irreproachable ideals – truth, God, the creation of life – the ripeness of death, eros, and waste.

By a similar token, philosopher Nick Land points out in his work on Bataille, The Thirst for Annihilation (2002), that while Plato’s allegorical sun (the illuminating truth of The Good) causes an equally allegorical, immaterial kind of pain – the pain of learning: of remembering long-forgotten truths – the pain of looking at the sun for Bataille is material, destructive, even fatal.

The difference is important in two ways central to Bataille’s thought: (1) Bataille’s sun does not exist in any sense for human minds, and does not cater to our senses, its force is annihilating, wasteful, and bordering on incomprehensible; (2) Bataille’s sun is a non-allegorical, physical thing, beholden to laws of matter and to the economy of energy that operates in nature – its light is potentially useful energy, squandered freely, and its radiance is enmeshed with the birth and death of all living creatures, all of whom are tasked with consuming the massive expenditure of the sun.

Desire, Extravagance, Reason: Georges Bataille’s Philosophical Legacy

Bataille’s attempts to theorize the ‘impossible’: states that seem to stand outside rationality and thorough description, like sexual ecstasy, the religious fervor of sacrifice, and moments of extreme suffering or physical pain. Though it is difficult to trace Bataille’s influence wherever it goes, frequently seeming to crop up without mentioning his name (perhaps because of the lingering pornographic reputation of Story of The Eye, and the unconventional, often literary style of Bataille’s works of philosophy), this thread of the impossible can be picked up in much post-structuralist theory and literary criticism.

Both Lacan and Foucault – the former while barely mentioning his name and the latter explicitly – draw upon Bataille’s ideas about desire and death, their proximity to one another; sexuality and the expenditure of energy; and what Foucault coins as ‘limit experiences’, these moments in which we draw nearer to the impossible.

Clearest of all, however, is the importance of Bataille’s ideas about communication and subjecthood. With significance for fiction-writers, psychoanalysts, critical theorists, and philosophers of language, Bataille’s suggestion that we can overcome the gulf between individual minds in states of extremity and impossibility has enormous explanatory and pragmatic power. It is not just that his vision, of the boundaries of our individual consciousnesses dissolving in the face of ecstasy and death, convincingly links together apparently disparate rituals and states, but that – as The Accursed Share attempts to lay out – we should systematically seek out those states as an ethical and political imperative, at least some of the time.