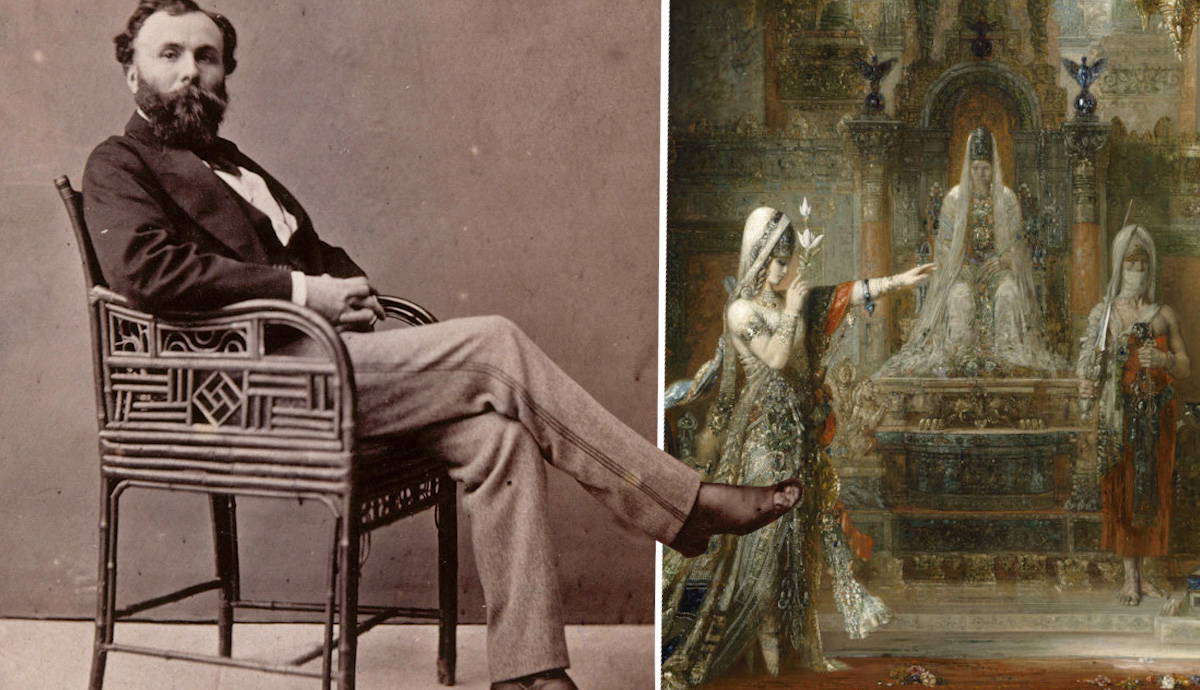

Gustave Moreau began his career as a one-note academic painter in France. Following a period of self-imposed isolation, he reinvented himself completely, experiencing an unparalleled artistic rebirth. Today, Moreau is remembered as a visionary whose intense, mystical paintings challenged the status quo of late 19th-century art. His work had a significant impact on the Symbolist movement of the time, and his teachings influenced a future generation of Fauvist artists. Here is a brief overview of the life of brilliant artist Gustave Moreau.

Early Life of Gustave Moreau

Gustave Moreau was born in France in 1826 to an architect father and a musician mother. The artistic family soon welcomed another member; Gustave’s sister, Camille. Gustave enjoyed a comfortable childhood; he was purported to be a sickly child and was coddled by his mother.

Moreau was sent to boarding school in 1836, as was common for the time, but returned home following the death of his sister. He was subsequently educated by his father, with a focus on the Classics.

Interested in drawing from a young age, Moreau’s artistic inclinations were inflamed when, at the age of 15, he visited Rome for the first time. Traveling through Italy with his mother, aunt, and uncle, Gustave was exposed for the first time to the Byzantine art that would so heavily influence his later work. Moreau would keep the sketchbook he filled on this trip for the rest of his life.

After finishing his education, Moreau began preparing for the entrance exam to the School of Fine Arts in Paris under the tutelage of artist François Picot, a neoclassical painter who also mentored Alexandre Cabanel.

Artistic Education & Influences

Moreau was granted acceptance to the School of Fine arts in 1846. He spent three years studying there but left after failing to win the prestigious Prix de Rome, a scholarship that granted French art students a stipend to study the Old Masters in Italy.

Moreau enjoyed a modicum of success upon leaving school, but the course of his career was changed when he crossed paths with fellow artist Théodore Chassériau. Chassériau had spent his childhood training with Ingres, a Neoclassical Academic master, and won his first award at the Paris Salon when he was just 17.

By the time he met Gustave Moreau in 1851, Chassériau had fallen out with his longtime mentor after becoming disillusioned with academic art. Both Chassériau and Moreau were intrigued by the more Romantic art of Ingres’ rival, Eugène Delacroix. The young artists became fast friends, working out of studios next door to each other.

The year 1852 was a landmark year for Moreau. One of his paintings, a Pieta, was accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon, and his parents purchased a home for him in Paris. Moreau set up a studio on the third floor and enjoyed all the city had to offer.

Old Friends and New

Tragically, Théodore Chassériau died following an illness in 1856 at the young age of 37.

Gustave returned to Italy in the wake of his good friend’s death, spending two years traveling and studying the Old Masters. It was on this journey that he would meet realist painter and future Impressionist Edgar Degas, with whom he would enjoy a long professional friendship (Degas would even paint Moreau’s portrait a few years after their meeting). Though the two had vastly different artistic styles, Degas was known to value Moreau’s advice.

It was upon his return to Paris in 1859 that Moreau would be introduced to the woman with whom he would share the next 30 years: Adelaide-Alexandrine Dureux.

The details surrounding the close relationship between Moreau and Dureux – including how the pair met – are murky. Opinions are divided on whether the relationship was platonic, romantic, or sexual, with some speculating that Moreau may have been homosexual. Regardless, the two never lived together, and neither person ever married.

Gustave referred to Dureux (who went by Alexandrine and was a decade Moreau’s junior) as his “best and only friend.”

A Period of Solitude

In 1864, Moreau exhibited Oedipus and the Sphinx at the Paris Salon. The painting (quickly purchased by Prince Napoleon III) was incredibly well-received, encouraging the artist to produce more pieces in the same vein. After a few years, however, tastes had apparently changed. Moreau’s submissions to the 1869 Salon received harsh criticism, causing the artist to withdraw from exhibiting his work and go into a period of extreme isolation.

For seven years, Gustave Moreau sequestered himself in his home studio, where he obsessively read, studied, and painted. He saw few people outside of Alexandrine and his mother, to whom he remained extremely close.

Moreau drew inspiration from Byzantine art, religious and mythological texts, and Eastern ornamentation and aesthetics. At the end of his self-imposed quarantine, Moreau’s art had evolved into something entirely new; a moody, organic, ornate, esoteric style that would come to be known as symbolism.

Artistic Rebirth

In 1876, Moreau burst back onto the Salon scene with the fascinating, provocative submission of two paintings: Salome Dancing Before Herod and The Apparition. The paintings were gorgeously executed, featuring intricate architecture, religious iconography, and rich fabrics flecked with gold and encrusted with gems.

The paintings caused a sensation. It would not be the last time Moreau would paint Salome (a seductive biblical figure who instigated the execution of John the Baptist). In fact, the artist came to be known for painting notorious femmes fatales.

Of course, there were detractors. One critic likened Moreau’s elaborate new paintings to riddles, citing their “meticulous and pretentious symbolism” and “childish” ornamentation. Still, the response to Moreau’s reinvention was overwhelmingly positive, and the artist would go on to present six paintings at the 1878 Universal Exhibition in Paris.

Moreau followed up his success with a series of fantastical watercolor illustrations for French author Jean de la Fontaine’s Fables series and by participating in one final Paris Salon.

In Mourning

The next decade would be one of extreme highs and lows for Moreau. In 1883, he was inducted into the French Legion of Honor for his contributions to French society. The very next year, his beloved mother died, sending the artist into a period of intense grief.

In 1888, he was elected to the Academy of Fine Arts, a long-awaited honor. Two years later, the artist mourned the death of his longtime companion, Alexandrine. In the wake of her passing, Moreau inexplicably burned their correspondence, sparking further speculation about their nontraditional relationship. Later, he would paint Orpheus at the Tomb of Eurydice in her honor.

Around the same time, Moreau began teaching at a studio run by the Academy. His students included future celebrated painters Henri Matisse and Georges Rouault, credited with founding the bright, bold Fauvist style. Unlike the Academy professors who came before him, Moreau encouraged his students to use their imaginations, experiment with color, and play to their own strengths rather than adopt his techniques. He also sent them to French museums to study and make copies of Renaissance art, just as he had done in his youth.

Gustave Moreau’s Final Years

Gustave Moreau painted his final masterpiece, Jupiter and Semele, in 1895. Three years later, the artist succumbed to stomach cancer at the age of 72. He is buried in Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. Though Moreau lived a quiet life, never achieving great fame outside of France, his influence was distinct.

Two years after Moreau’s death, Cuban-born French poet Jose-Maria de Heredia published a book of sonnets largely inspired by Moreau’s art. His 13th sonnet, Jason and Medea, was specifically dedicated to Moreau, who completed a painting by the same name during his period of isolation.

Moreau also significantly influenced the Surrealist movement, though it would not emerge until 20 years after his death. The movement’s foremost artist, André Breton, said that seeing Moreau’s paintings as a teenager “influenced forever my idea of love.” When Breton’s contemporary Salvador Dali (a name synonymous with Surrealism) held a press conference to announce the opening of his Theatre Museum in Spain, he did so in Moreau’s home museum in France.

Most importantly, Moreau was remembered fondly by his students. Georges Rouault, purportedly a favorite of the artist, even created a lithograph of his mentor a full 30 years after Moreau’s death.

Moreau left his multi-storied home – filled with over ten thousand works of art in various states of completion – to the state. The house now functions as a museum dedicated to the artist: his life, his stunning work, and his legacy as the founder of symbolist art.