Martin Heidegger wanted to give an account of how we can move from the way we ordinarily make sense of things to an awareness of things in themselves. This article explores his phenomenological method, which can be seen as the framework within which he makes an attempt to do just that—to move from experience and “natural” processes of explanation to a more fundamental kind of understanding, or an understanding of things more fundamentally.

This article begins with a discussion of Heidegger’s life, especially his relationship with his intellectual forebear Edmund Husserl. It then proceeds by offering various definitions of phenomenology, and exploring how Heidegger develops away from Husserl’s theory. It concludes with a discussion of the phenomenological method and Heidegger’s attempt to distinguish two forms of “being.”

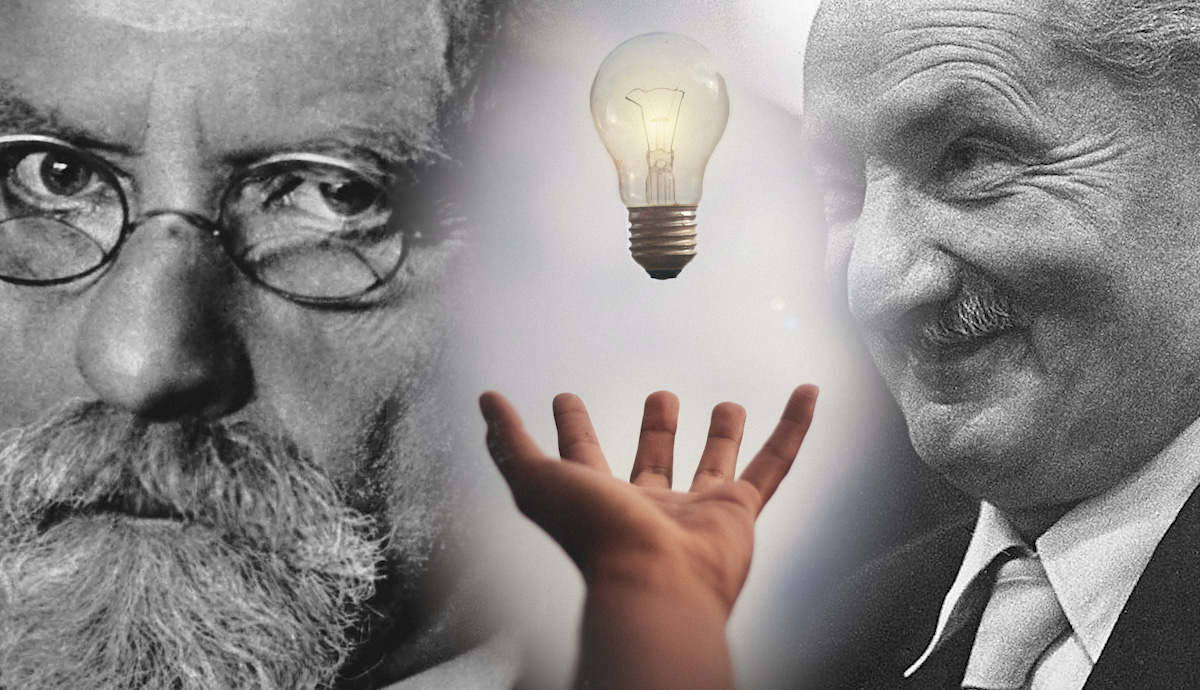

Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl

Heidegger’s philosophy is difficult to understand without some prior context. The method of Heidegger’s philosophy is associated with that of phenomenology, which was developed (in the form which Heidegger adapted) by Edmund Husserl. Certainly, attempting to figure out how Heidegger conceives of experience, given sensory impressions, and the natural basis for knowledge, requires us to reckon with the relationship between Heidegger and Husserl.

Husserl was one of Heidegger’s major philosophical influences, and Heidegger’s dedication to his most famous book, Being and Time, honors Husserl. The relationship between the two philosophers remains the subject of great debate, both philosophical and historical. The historical dimension hinges on the simple fact that Husserl was a Jew and Heidegger a Nazi sympathizer and anti-Semite. In spite of Heidegger’s philosophical debt to Husserl, Heidegger chose to accede to the position of their shared university (the University of Freiburg), weeks after Husserl was banned from using its library on anti-Semitic grounds. Heidegger also allowed a wartime edition of Being and Time to be published without the dedication to Husserl.

As a last bit of preamble, it is worth saying something about Heidegger’s style. Heidegger has developed a reputation for obscurity, and this is partly due to Being and Time subsuming the interest given to his work, in spite of its density and idiosyncrasy. Even if some of the terminology in this article makes Heidegger’s work sound formidable, that is not to be taken as representative of wilful obscurity as such—unorthodox turns of phrase are easy to misunderstand when taken out of context, as due to its length this article inevitably must (to some extent).

Experience and Knowledge

Having said that, Heidegger is not against attempting to associate various connotations with a single term. Heidegger’s conception of experience and knowledge is developed through his conception of phenomenology. There are various ways of understanding phenomenology, as it is defined in different ways at different moments.

As Adrian Moore points out, Heidegger himself was a big believer in etymological analysis, so we might as well start with the observation that phenomenology is composed of two Ancient Greek words, phenomenon and logos. Phenomenon can be translated as “that which shows itself.” This is the element that contains (among other things) sense experience. Logos is trickier—it has many meanings (word, concept, reason), but Heidegger’s interpretation of logos is that it is equivalent to “discourse,” specifically a discourse that is a manifestation of its subject.

This allows us to move to our first, provisional attempt to define phenomenology—it is an attempt to make sense of what is manifest in what shows itself. In other words, it is a kind of second-order investigation of the way in which we make sense of things “naturally.” It is not the act of making sense of what is immediately given, but is about making sense of this in the context of sense-making.

Phenomenology: Further Distinctions

This is potentially the most straightforward definition of phenomenology. We tend to make sense of the world around us in a certain way even before we know what philosophy is. We make naïve judgments, we integrate them into whatever broader framework of understanding. Phenomenology is an attempt to understand the former in the context of the latter.

This simple definition of phenomenology has been endlessly reused in various other areas of the humanities, partly because it provides a neat and sophisticated-sounding term to label the study of experience. Things are, however, not nearly so simple for Heidegger.

There are three core elements of phenomenology for Heidegger: intentionality, categorial intuition, and the a priori. We need to understand how all three of these relate to one another if we are to understand Heidegger’s phenomenology.

Intentionality is a strictly Husserlian innovation, and the term is being used broadly as a way of referring to the way in which mental acts involve “turning” the mind towards objects; mental acts are about things, they are directed at things.

In other words, any mental act has an object. We don’t merely perceive, but we perceive something. We don’t merely understand, we understand something. Intentionality is so important to Husserl because it is intentionality that allows him to argue that the mind and its objects are not two distinct entities, but are rather two aspects of the same thing, that physical objects are constituted by unities in experience. In addition to this, it lets Husserl defend the idea that it is the subjective ego that is the most fundamental, irreducible component of our attempt to understand things as they are.

Categorial intuition can be understood as the abstract, structural essence of a given thing. In other words, categorial intuitions represent things like “number,” “universality” and so on.

The a priori is typically understood as an epistemological category—as saying something about the way in which we know a certain thing regardless of experience, with its opposing concept of the a posteriori. For Heidegger, it is a consequence of the development of the phenomenological method that the a priori is no longer a way of knowing, but of being. The a priori in this new sense is composed of the two other concepts—the a priori is an intentional object of categorial intuition.

Breaking With Husserl

Here we come to another attempt by Heidegger to define just what phenomenology is. He describes it as “the analytic description of intentionality in its a priori.” Yet even then, we haven’t really exhausted the meaning of phenomenology in Heidegger’s philosophy. Indeed, up until this point, we have not said much about Heidegger’s theory that we might not also have said of Husserl’s. Yet Heidegger’s thought is, in certain important ways, a real break from Husserl’s.

Phenomenology can be described as meta-epistemological. It is an attempt to know how we naturally attempt to know how things are. Heidegger breaks with Husserl at the point when the latter posits a fixed point which is the subject of all possible sense-making. This is the transcendental ego. Transcendental here simply means that which is necessary to experience. Heidegger is happy to agree that there is a subject of all possible attempts to know, but wants us to go beyond the Husserlian conception of the subject as somehow basic and therefore unanalysable in itself.

The point of real contention between Husserl and Heidegger can be explained in this way. Heidegger wants to turn phenomenology on the subject itself, rather than preserve it as the fixed point of the “phenomenological reduction.”

For Heidegger, the self cannot be extricated from its surrounding, and therefore attempts to make sense of things must necessarily attempt to make sense of the self as well (“we are ourselves beings to be analysed”).

If the insight of phenomenology is that we are given things, we think and attempt to understand due to relations of intentionality between us and said things, following that thought through means that we do not have to fixate on the self as the ne plus ultra (the point beyond which we cannot go any further) of philosophical inquiry.

The term Moore uses for Heidegger’s approach is “synoptic,” meaning literally “seen together”—he takes a synoptic approach to our ways of knowing and the objects of knowledge.

Being and being in Martin Heidegger’s Philosophy

What does this mean in practice? Here we can conclude by exploring a distinction Heidegger takes to be more basic than that between the transcendental subject and the objects of thought: the distinction between Being (with a capital B) and being (with no capital).

Whereas Being stands for things just as they are, being stands for things as we come to know them. We participate in Being just as much as the objects we come to know do. Heidegger’s project begins with an attempt to separate these two senses of the same word (to know the “meaning of being”). He believes that if we begin with being, we can then proceed to Being through them.

Heidegger uses these concepts to draw a clear distinction between his philosophical inheritance and his own contribution to philosophy—that is, between Husserl and himself. Husserl makes the phenomenological reduction to lead us from “the natural attitude of the human being” to the “transcendental life of consciousness…in which objects are constituted as correlates of consciousness”.

For Heidegger, phenomenological reduction leads us from understanding being to understanding the correlative Being. There is nothing natural about the attempt to understand the latter. Doing so involves going beyond all that is given, including experience and pre-reflective attempts at understanding it.