After the rise and fall of the Nazi regime, Horkheimer was left wondering how such a catastrophe could have possibly unfolded. The 20th century was marked by the most impressive scientific and industrial achievements ever witnessed by man, yet at the same time, it was tainted with the blood of millions, with wars, massacres, and the explosion of barbarism incomparable to any previous tragedies in its scale. How could this have happened? How could we have made so much progress with reason in the instrumental sphere, yet somehow moved backwards with reason ethically? Was reason decoupled from its ethical aims?

Horkheimer on The Insidious Nature of Tolerance: To Each Their Own

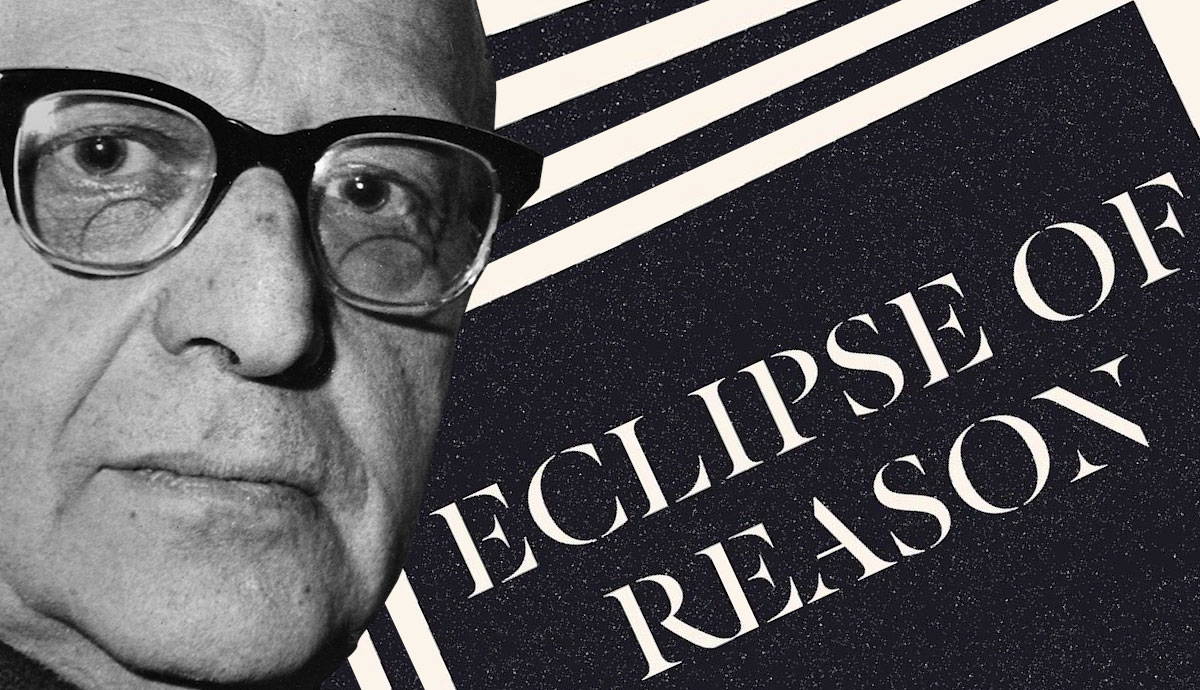

Horkheimer opens his book “The eclipse of reason” by noting a shift that has occurred in the conception of reason: from an objective reason which was inherent in the structure of reality to a subjective reason which existed only in the subject and was concerned only with the achievement of specific goals. As to what or why the goals are what they are, it couldn’t matter less to subjective reason. It is only focused on the coordination of the means to the end. The ends themselves aren’t subject to reason.

Subjective reason here enters a stage of formalization. Thought becomes a tool, completely divorced from its previous entanglement in ethics. Reason went from being the instrument that determined what ends should be followed to a one-dimensional force that could only help us achieve said ends, but not examine or determine them.

Today, in most western societies, tolerance is said to be one of its most fundamental attributes. It implies that people can live very different lives, based on very different ethical values, and somehow still manage to function within the same society. Each individual seems to live within their own bubble, within their own truth. Horkheimer notes that this development came with the emergence of subjective reason. This wasn’t always the case. Horkheimer notes that for most of our civilization, truth wasn’t subjective but objective, tied to a reality that was the same for everyone else. Hence it made no sense of speaking about different truths. There’s just a single truth, a single reality that we can either interpret correctly or incorrectly.

This view of reality also determined ethical values, which were previously all connected to various theological ontologies. With subjective reason, religion or various ontologies become just another cultural commodity that one could choose to appropriate as part of their own identity, as part of their self. Reason ceased to be an organ that could penetrate the true nature of reality but was instead rendered simply instrumental, given the role of coordination, maximization, and optimization. It became a one-dimensional driver of functionality. The logic of the division of labor is transferred to the division of spirit:

“The pattern of the social division of labor is automatically transferred to the life of the spirit, and this division of the realm of culture is a corollary to the replacement of universal objective truth by formalized, inherently relativist reason.”

The decline of philosophy – what’s the problem with that?

Horkheimer notes that the importance of philosophical thinking has diminished with time. Especially with the huge scientific leaps achieved in the 20th century, philosophy seemed to have been made obsolete, dealing with meaningless problems that were of no use to anyone, like a dog chasing its own tail.

The only philosophers left were logical positivists or analytical philosophers who reduced philosophy to simply being a tool for clarification and eliminating ambiguity. The positivists claimed that if science was used for destruction, this was simply a perverted usage. In response to subjective reason, metaphysicians and theologians attempt to revive dead ontologies. To Horkheimer, this is unsatisfactory. The arrival of subjective reason wasn’t accidental, and it can’t simply be reversed through a return to old philosophies or structures of government.

Subjective reason was able to triumph over these ontologies because their basis was weak and doomed to destruction, sooner or later. Their revival is completely artificial, a nostalgic, impotent act that doesn’t challenge the emergence of instrumental reason in the slightest. The decline of philosophical thinking is a symptom that accompanies instrumental reason, mainly because the point of philosophical thinking isn’t to achieve some goal; it is done for its own sake. The age of instrumental reason is skeptical of everything that is done for its own sake, everything that isn’t used in order to get something out of it.

The decline of philosophical thinking makes possible the emergence of totalitarian systems. Even in cases where philosophy survives, it was solely tied to propelling the myth of the totalitarian regime. It was supplementary. Society becomes incapable of an intellectual means of resistance against an ever-growing dogma of Scientism.

The Age of Nihilism

With no philosophical backbone to understand their own development, societies grow nihilistic and stand ethically directionless. Everything outside of the subject is seen as a means to achieve something, as a tool to be used, and repurposed.

Nature goes through this process as well. Its fundamental connection with us is reified. It is now only seen as a collection of stuff, wood to be chopped off, animals to be hunted, water to produce electricity, and coal to be dragged out from the depth of the earth. The subject then finally starts treating himself as an object; it stands at a distance from his/her own self.

“The total transformation of each and every realm of being into a field of means leads to the liquidation of the subject who is supposed to use them. This gives modern industrialist society its nihilistic aspect. Subjectivization, which exalts the subject, also dooms him.”

The domination of nature is, at the same time, the domination of man. Man must fight nature everywhere it is found, and soon enough, he finds out there’s quite a lot of nature in him, nature that needs to be subjugated and controlled. This process of internalized domination leads to dehumanization. All that is human is decentered to make place for all that is useful. Through this process, nature isn’t really transcended but merely repressed, swept under the rug of a purely functional mode of being in the world.

The Cost of Repression

This repression of nature has expressed itself in its most brutal form in totalitarian regimes. Before, the idealist subject tried to adjust reality to its absolute ideal; now, it is reality which adjusts the subject, reducing him to a technical operation that needs to adapt to ever-growing industries.

Horkheimer saw that workers in his time had become more flexible than ever. Salesmen today, artists tomorrow, managers the next month, and train operators the following year. What is left of the ego that characterizes this form of being? Nothing but a shapeless potentiality, free of identity, ready to be transformed into whatever is demanded of it.

Economic and social forces create a pseudo-natural environment to which the ego adapts blindly. The only reason for existence becomes domination. Intelligence is equated with one’s ability to adapt to changing conditions, to comply with new rules or ways of functioning. If this is intelligence, it is only the intelligence of the slave who accepts his subjugated place in the world a priori. Forms of government are just patterns one should adapt to, just like you adapt when you see a strong curve sign coming ahead in the road or when a machine in the workshop is replaced with a more efficient one.

Domination of the self brings conformity to the Other. Reflection which looks inwards is abandoned for what looks outwards, a mode of thought which is always waiting for the next moment, a nihilistic pragmatism. Horkheimer acknowledges that pragmatism is not new, but its claim to the totality of reason is a product of the formation of new dynamics.

Horkheimer on the Role of Philosophy – or What is Left of It

In the wake of instrumental reason, philosophy remains its only threat. The task of philosophy, for Horkheimer, becomes to offer an alternative to subjective reason which should hopefully get the masses to start resisting its totalizing conformity. This can’t be done by trying to turn back time, fetishizing the past, or reviving dead and buried ontologies. The way to resist is by daring to think forthe sake of thinking, by not giving up the critical capabilities humans are endowed with for the sake of conformity, and by embracing even that which doesn’t produce or is useful. Philosophy alone has the power to “foreshadow the path of progress as it is marked out by logical and factual necessities”.

It is a cliché that philosophy today has become irrelevant in public discourse. The only traces of it which remain are in the form of the self-help genre or French existentialism which is also mostly used in the context of self-help. Simply put, only those parts of philosophy which can be reintegrated within instrumental reason, which serve to help us achieve something we want, have survived in public discourse.

According to public perception, a “philosopher” is someone who sits around overthinking things that do not even matter, worrying about pointless conundrums. Instrumental reason sees itself triumphant against philosophical reflection. Every human activity needs to yield some tangible result, it needs to produce something. “What do you gain by doing this?” people ask the philosopher. The philosopher should respond: “What you’ve already lost”.