German post-war artist Joseph Beuys has a long-standing reputation for his connection to the ancient practice of Shamanism. Throughout his career he cultivated a public persona as an enigmatic shaman figure, deeply connected to nature, animals, man’s primitive past, and the unseen spiritual world. He integrated these themes into his art through strange performances, rituals, and teaching practices, earning a moniker as “the Shaman of Modern Art.” We look through the key themes of Shamanism that Beuys adopted, which encouraged a message of healing, transformation and regeneration through art after the horrors of World War II.

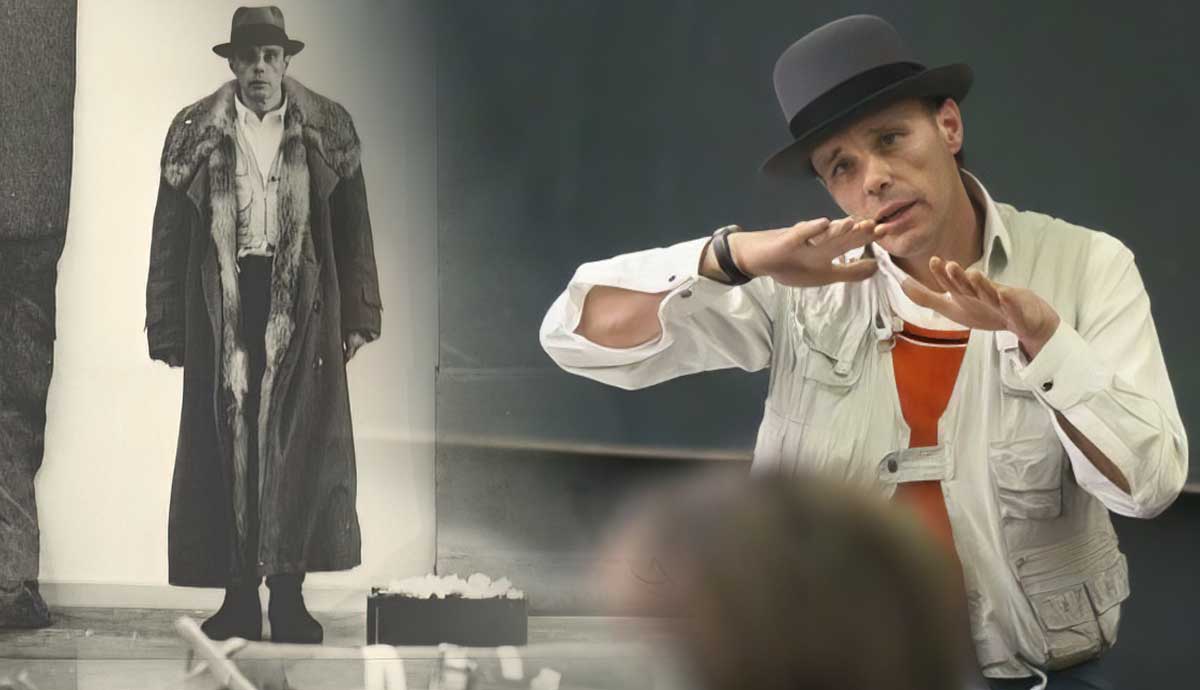

Joseph Beuys Created a Mysterious Persona

Joseph Beuys grew up against the backdrop of war, and he had experienced first hand the trauma of battle and conflict as a young man. He invented the now legendary story that he was rescued by Tartar tribesmen after being shot down in the Crimean Mountains. Beuys then claimed that they wrapped him in layers of felt and fat to keep him warm. While the rescue aspect of the story has largely been disproved, the myth he created encapsulated his fascination with indigenous cultures and the healing power of natural materials. This story first connected Beuys to the notion of Shamanism, and played a vital role in creating Beuys’s strange and elusive persona.

He Wanted to Heal and Transform Society Through Art

Beuys connected deeply with how a shaman figure could encourage healing, regeneration and transformation. These themes were particularly potent to Beuys in the wake of World War II, when a deeply wounded society needed to heal and mend itself. He integrated these healing aspects of Shamanism into many of his most profound works of art, which opened up room for spiritual contemplation and conveyed a message of hope and optimism for a new world.

His installation The End of the 20th Century, 1983-5, is one of the most resonant examples. In this artwork Beuys drilled holes into 31 lumps of basalt rocks, removing a cone shaped section. He then inserted felt and clay into the holes, before putting the cones back in place. Beuys has argued that this process of removing and putting back the rock in a new way opens up ideas around the healing of old wounds and the start of a new life cycle.

Joseph Beuys Cared About the Environment

Another aspect of Shamanism adopted by Beuys in his art was a connection with the environment. He believed that in order to instill a new world order we needed to look back to pre-war cultures when people were more in tune with the natural world, and its many healing properties. Through art, intervention and performance, Beuys drew our attention to the ways we should be trying to re-integrate nature back into urban living, in order to reap all the benefits it has to offer.

Beuys also saw working with natural materials and environmental themes as a way of harking back to the German pre-war tradition for Romanticism and a sublime celebration of nature, through artists such as Caspar David Friedrich and Albert Bierstadt. Beuys’s project 7000 Oaks, city forestation instead of city administration, 1982, involved planting trees all across the Germany city of Kassel, pairing each tree with a piece of basalt stone.

He Formed a Spiritual Connection with Animals

Beuys was fascinated by the connection between humans and animals. In one of his most iconic performances, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, 1965, Beuys cradles a dead hare while describing a series of artworks to the animal in a strange, quasi-spiritual act. Meanwhile, in Beuys’s legendary performance I Like America and America Likes Me, 1974, (sometimes also called Coyote), Beuys locked himself in a room with a wild coyote, in order to prove that human beings can exist alongside even the most ferocious of wild animals.

Beuys Wanted to Overthrow Systems of Power

Beuys became professor of monumental sculpture at Dusseldorf Academy in 1961. In his role as an educator he extended his conceptual framework of Shamanism, styling himself as a kind of Fluxus guru or spiritual leader rather than a formalized instructor. He removed entry requirements, insisting any student could join his experimental classes. He also did away with examinations, focusing instead on individual expression in an attempt to overthrow traditional systems of power. It was a radical approach to teaching that had a lasting influence not only on art education, but the very nature of art, merging teaching with activism and performance art, even if it eventually cost him his teaching job at Dusseldorf Academy.