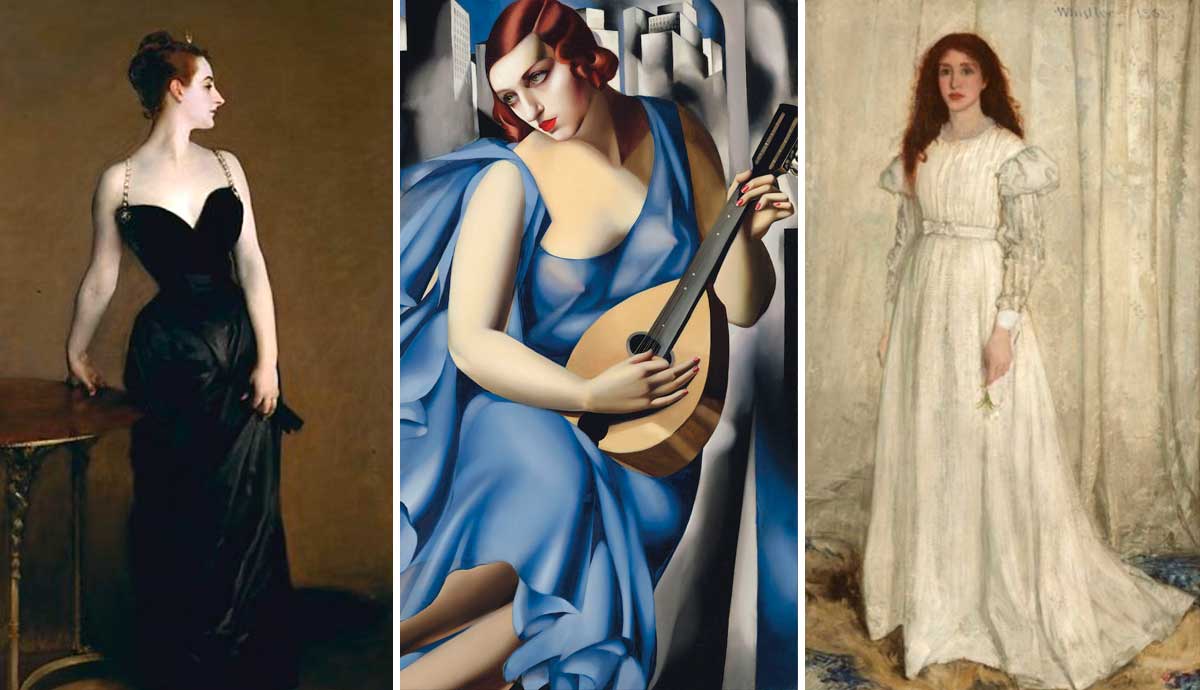

American expat painter John Singer Sargent was flying high in late 19th century Parisian art circles, taking on portrait commissions from some of society’s wealthiest and most prestigious clients. But all that came crashing to a halt when Sargent painted a portrait of the well-connected socialite Virginie Amelie Avegno Gautreau, the American wife of a French banker, in 1883. Unveiled at the Paris Salon in 1884, the painting caused such an uproar that it ruined both Sargent and Gautreau’s reputations. Sargent subsequently renamed the artwork as the anonymous Madame X, and fled to the UK to begin again. Meanwhile, the scandal left Gautreau’s reputation in tatters. But what was it about this seemingly innocuous painting that caused so much controversy, and how did it nearly ruin Sargent’s entire career?

1. Madame X Wore a Risqué Dress

Actually, it wasn’t so much the dress that caused scandal among Parisian audiences, but more the way Gautreau wore it. The deep v of the bodice exposed just a little too much flesh for genteel Parisians, and it seemed a little too large for the model’s figure, sitting away from her bustline. Added to that was the fallen jeweled strap, which revealed the model’s bare shoulder, and made it look like her entire dress might just slip off at any moment. A scathing critic at the time wrote, “One more struggle and the lady will be free.”

Sargent later repainted Gautreau’s strap lifted up, but the damage was done. However, as is so often the way, the notoriety of Madame X’s dress later made it an iconic emblem of its time. In 1960, Cuban-American fashion designer Luis Estevez designed a similar black dress based on Gautreau’s outfit, and it went on to feature in LIFE magazine in the same year, worn by the actress Dina Merrill. Since then, similar variations on the dress have appeared on countless fashion shows and red carpet events, demonstrating just once instance where art has inspired fashion.

2. Her Pose Was Coquettish

The pose assumed by Mme Gautreau might look quite tame by today’s standards, but in 19th century Paris, it was considered entirely unacceptable. In contrast with the more staid, upright positions of formal portraits, the dynamic, twisted pose she assumes has a coquettish, flirtatious quality. Thus, Sargent displayed the model’s brazen confidence in the power of her own beauty, as opposed to the coy and demure nature of other models. Almost immediately, poor Gautreau’s reputation was in tatters, with rumors circulating about her loose morals and infidelities. Caricatures appeared in newspapers, and Gautreau became a laughing stock. Gautreau’s mother was furious, declaring, “All Paris is making fun of my daughter … She is ruined. My people will be forced to defend themselves. She’ll die of chagrin.”

Unfortunately, Gautreau never fully recovered, retreating into exile for a long time. When she did eventually emerge, Gautreau had two other portraits painted which restored her reputation somewhat, one by Antonio de la Gandara, and one by Gustave Cortois, which also featured a dropped sleeve, but in a more demure style.

3. Her Skin Was Too Pale

Critics shamed Sargent for emphasizing the ghostly pallor of Gautreau’s skin, calling it “almost bluish.” Rumor had it Gautreau achieved such a pale complexion by taking small doses or arsenic, and using lavender powder to emphasize it. Whether intentional or not, Sargent’s painting seemed to emphasize the model’s use of such makeup, by painting her ear considerably pinker than her face. Wearing so much make-up was unseemly for a respectable lady in 19th century Paris, thus furthering the scandal of the artwork.

4. Madame X Later Moved to the United States

Understandably, Gautreau’s family showed little interest in keeping the portrait, so Sargent took it with him when he moved to the UK, and kept it in his studio for a long time. There he was able to build a new reputation as a society portraitist. Many years later, in 1916 Sargent eventually sold Madame X to the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York, by which point the painting’s scandal had become a major selling point. Sargent even wrote to the director of the Met, “I suppose it is the best thing I have ever done.”