The origins of the qipao, also known as cheongsam, can be traced to the turn of the 20th century, against the backdrop of political and social upheaval in China. The qipao has its roots in the long robes worn by Manchu women during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912). It later evolved into the iconic figure-hugging dress characterized by a side slit and a high cylindrical collar which we know today. A symbol of liberation and sensuality, the qipao shapes and has been shaped by the shifting silhouettes of Chinese society through the tides of time.

Imperial Times: Qipao as the Outfit of the Upper Class

The Manchurian people, also known as the Qiren or Banner People, ruled China during the Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1912). To distinguish themselves from the ordinary people, usually the Han Chinese, the Manchu minority made it mandatory to wear different clothing. Like their male counterparts who donned the changpao or long robe, Manchu women wore long, loose-fitting silk gowns called the qipao. Designed to hide a woman’s body straight down to the ankles, the qipao featured a slit on either side of the gown that allowed for easy movement while on horseback.

To better protect and cover their legs, Manchu women would often wear trousers under the gown. While it was not meant to accentuate the female figure, the qipao soon evolved to feature ornamentation such as beads, gemstones, and floral embroidery. These elaborate designs gave the qipao an added feminine touch that further differentiated it from the manly Manchurian robes.

A New Era: The Dawn of Social Change

Following the collapse of imperial rule in China, the post-Qing Chinese society underwent a seismic transformation. From the mid-1910s, the literati, influenced by Western ideals of liberation, began advocating for women to be freed from the shackles of patriarchy and tradition. In all corners of society, women were emerging from domesticity and into public spheres – receiving education, taking on jobs, and even entering politics. This accelerated momentum of change soon influenced the way women viewed their dressing and fashion choices.

During the May Fourth Movement in 1919, empowered female students took to the streets to assert equality while donning the changpao associated with male intellectuals. This time, however, the trousers underneath the gowns gave way to full-length stockings. As a fashion statement that celebrated feminine liberation, it was also a nod to the changing circumstances. Despite being experimental, this new style soon captivated and influenced women in major cities like Shanghai – the eventual birthplace of the modern-day qipao.

A Golden Age: Shanghai and the Skin-Hugging Qipao

Hailed as the Paris of the East, Shanghai in the late 1920s was a seductive concoction of glamor, sin, and all things fashionable. It was here at the crossroads of western and eastern influences where the qipao as we know it today began to take shape. The loose-fit iconic of the Manchurian robes of the yesteryears was ditched in favor of more figure-hugging and slender shapes.

The qipao designs of this time boasted shorter sleeves, longer slits, and a high, stiff collar asymmetrically fastened by a pankou (traditional knotted button). These elements allowed women to maintain their poise and posture, while teasingly revealing a bit of flesh as they sauntered down the streets now filled with smoky dance halls and movie theatres. Influences from the western world also began to leave an imprint on the qipao styles of this time. As with tapered waists, it was common to see distinctively Art Deco motifs on qipaos that were of the flapper-approved calf lengths.

By this time, the qipao had become the quintessential garment worn by women of all social classes. From socialites to cabaret dancers, the qipao brought to life the sensuality innate in every Chinese woman, positioning itself as the new standard of modernity. Beyond the Chinese-speaking world, western audiences were also becoming increasingly enthralled by the qipao. It was a growing fascination said to be fuelled by the international appearances of qipao-clad former first ladies like Madame Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Wellington Koo.

Post-War Peril: The Qipao as a Dangerous Symbol

With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the glamour and flamboyance associated with the qipao in the 1920s and 1930s became increasingly muted. Against the backdrop of rising prices of fabrics and dampened spirits, qipao styles in this period were modest, to say the least. With the simple and restrained designs, qipaos served more of a functional rather than an aesthetic purpose for women during these times of uncertainty.

Despite a brief revival after the war, the qipao soon fell out of favor and became a symbol of Western bourgeois ideals, as communist influences swept through mainland China from 1949. Gone from the now-quiet streets of Shanghai was the fashionable and flirtatious qipao. In its place was the monochromatic tunic suit – also known as the Mao suit – that was deliberately designed to be gender-neutral. The suit was worn by males and females alike and espoused the egalitarian ideals which the Chinese society was subscribing to under the communist regime.

A Second Golden Age: The Cheongsam Craze in Hong Kong

While post-1949 China might have been unrecognizable and even depressing to those yearning for the glamour of Old Shanghai, it was in Hong Kong where the qipao was resurrected. Fearing for their wellbeing, many wealthy families had fled to the then-British colony which was regarded as a haven from communist rule. Here, the ladies continued to waltz down the streets in their tailor-made, sequin-adorned qipaos for their opulent afternoon tea parties in true Old Shanghainese style. Hong Kong in the 1950s and 1960s was indisputably the second golden age for the qipao. With Cantonese being the lingua franca of the city, this was also likely to be when qipao started being used interchangeably with and eventually replaced by the term cheongsam (meaning “long dress”). It was said that cheongsam was a preferred term because it was not gender-focused. Before western suits became popular in China, Chinese men used to wear long robes known also as the cheongsam. This was unlike qipao which has always been closely and solely associated with women’s garments.

Caught in a cheongsam craze, bespoke tailoring services helmed by native Shanghainese tailors began sprouting everywhere in the cosmopolitan city of Hong Kong. Not only was the qipao the rich’s vogue dress, it too became something to flaunt for working-class women who learned to sew them using cheaper materials. Reflecting the city’s liveliness, qipao designs of this time sported vibrant geometric and floral prints, along with western-influenced zips replacing the traditional knotted buttons. Qipaos with shorter hemlines – inspired by the rise of the mini-skirt in the west – also became popular among women. The classic Wong Kar Wai masterpiece In The Mood For Love (2000) was set in Hong Kong during this period. Seasoned cinephiles would recall being spellbound by the lovely Maggie Cheung, who was styled in over 20 qipaos reflecting the 1960s’ style in the film.

Gradual Decline: Fighting the Fervour of Fast Fashion

In its heyday during the post-war years, the qipao dominated every Chinese woman’s wardrobe. This did not only apply to Hong Kong, but was also observed elsewhere in Asia like Singapore, Taiwan, and societies with a sizable Chinese community. However, with the relentless tides of modernization and Western influences, the qipao soon found itself rivaling emerging fashion mainstays like casual T-shirts and pants. Ironically, the form-fitting quality of the qipao that had once attracted figure-conscious women became the very reason why it was no longer favored. Singaporean women in the 1970s readily ditched the qipao in favor of more loose clothing which would not hinder movement in their daily lives.

Driven by the twin forces of globalization and a preference for convenience, the onslaught of fast fashion relegated the qipao to a traditional dress reserved only for special occasions like weddings. This foreshadowed the gradual dwindling of the bespoke tailoring industry in many Asian societies. The evocative image of impeccably dressed women in qipaos sauntering down the streets in their high heels became but a memory of the distant past.

21st Century Resurgence: The Qipao is Bringing Sexy Back

With films like In The Mood For Love (2000) and Lust, Caution (2007) garnering international acclaim, a yearning for nostalgia precipitated demand for the cheongsam again. A new generation of younger female consumers is no longer seeing the qipao as a relic from their grandmothers’ wardrobes. Instead, it is increasingly viewed as a timeless heritage piece that could be reinvented with a modern-day fashion sense. This has given rise to innovative designs such as mandarin-collared jumpsuits and midi length qipaos suitable for all formal and informal occasions. Adding a modern twist to a traditional dress does not only reflect the creativity of contemporary dressmakers. It is also indicative of the versatility of the qipao and its quintessential elements that have stood the test of time.

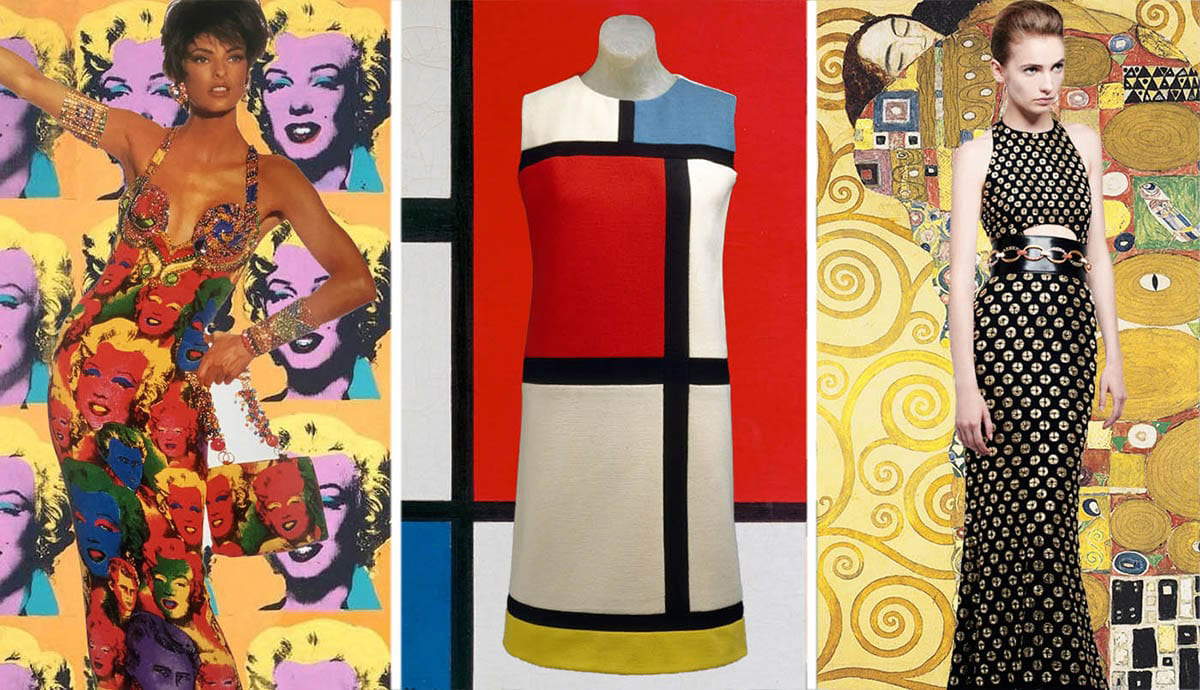

While the qipao makes its way back into the hearts of women all over the world, it has also successfully conquered haute couture. With cultural cross-pollination, Asian culture is increasingly looked to as a source of inspiration on international fashion runways. Famed designers like Jean Paul Gaultier, Guo Pei, and Yves Saint Laurent have paid tribute to the qipao by incorporating its elements in high-fashion pieces. With the qipao reimagined and reinvented, a new generation of western audiences is beginning to venture beyond the stereotypical representations of Chinese culture.

True to its versatility, the qipao has undergone political tumult, survived social upheavals, and become accustomed to changing economic patterns – each time emerging stronger than ever. The resurgent interest it is enjoying in this day and age has firmly cemented its significance as a symbolic marker of Chinese identity. Its prestige as a cultural emblem continues to inspire women from all cultural backgrounds who desire to add elegance and grace to their everyday wear. Synonymous with sensuality, sophistication, and enduring nostalgia, the qipao is here to stay in the wardrobes and the hearts of generations of women to come.