Has modern medicine led to overmedicalization? Ivan Illich argues that it has in his influential book Medical Nemesis. This article will explore some of Illich’s arguments, which range from the idea that there has been an institutional monopolization of care to the suggestion that people should be able to self-medicate.

Behind Medical Nemesis: The Life of Ivan Illich

Born in Vienna to a Catholic father and Jewish mother in 1926, Ivan Illich led an itinerant life. After his father’s death in 1943, Illich, then just 17, fled Nazi occupation to avoid persecution for his Jewish heritage. Spending time in Italy, he started his university education, before returning to Salzburg to study history, eventually gaining a PhD.

Turning away from an academic career, he trained as a Catholic priest, traveled to New York to minister to the Puerto Rican community, traveled South America on foot and horseback, and was tried for heresy at the Vatican for his criticism of the Catholic church’s missionary program. Dissatisfied with the church, Illich renounced the priesthood and returned to an academic career; taking up visiting professorships at US and European universities.

Perhaps most famous for his criticism of the school system in Deschooling Society (1971), Ivan Illich also railed against many of the other institutions of industrial society, including modern transportation, and the organization of work. In this article, we will look at Illich’s critique of modern medicine, put forward most extensively in Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health (1975).

Medical Nemesis

Medical Nemesis is not an easy read as Illich has an unfortunately obtuse writing style. He is overly fond of complex nouns, some of which he coins himself, making his prose dense and obscuring the thread of the main argument. Illich is also prone to overstating his case, selectively picking historical details that support his point, and repeating himself. Nonetheless, despite these flaws, the argument he makes remains powerful.

At its core, Illich argues that medicine, far from having reduced human suffering, is actually the cause of much contemporary ill health. Illich diagnosed three forms of iatrogenesis (i.e., harm brought about by medicine or caused by a healthcare intervention).

The first is clinical iatrogenesis. Clinical iatrogenesis occurs when ineffective and toxic treatments cause patient harm. Although medical treatment has succeeded in controlling some diseases and alleviating some symptoms, these diseases have simply been replaced by chronic illnesses (Illich, 1976, p. 7). Many of these chronic illnesses will require continuous treatment. Given that many medications are poisonous at the wrong dose, we are increasingly exposed to medical harm. Moreover, even at the right dose, all medications have side effects, and when medications are combined, these side effects can worsen. The increased medicalization of society, therefore, doesn’t necessarily lead to better health.

The second form of iatrogenesis Illich considers is social iatrogenesis. Illich argues that more and more aspects of our lives are seen as amenable to medical intervention even if they are, at the base, caused by social problems such as poor housing, nutrition, or sanitation. As a consequence, people are disempowered from healing themselves and shaping their environments. The increased medicalization of society “tends to transform personal responsibility for my future into my management by some agency.” (Illich, 1976, p. 30).

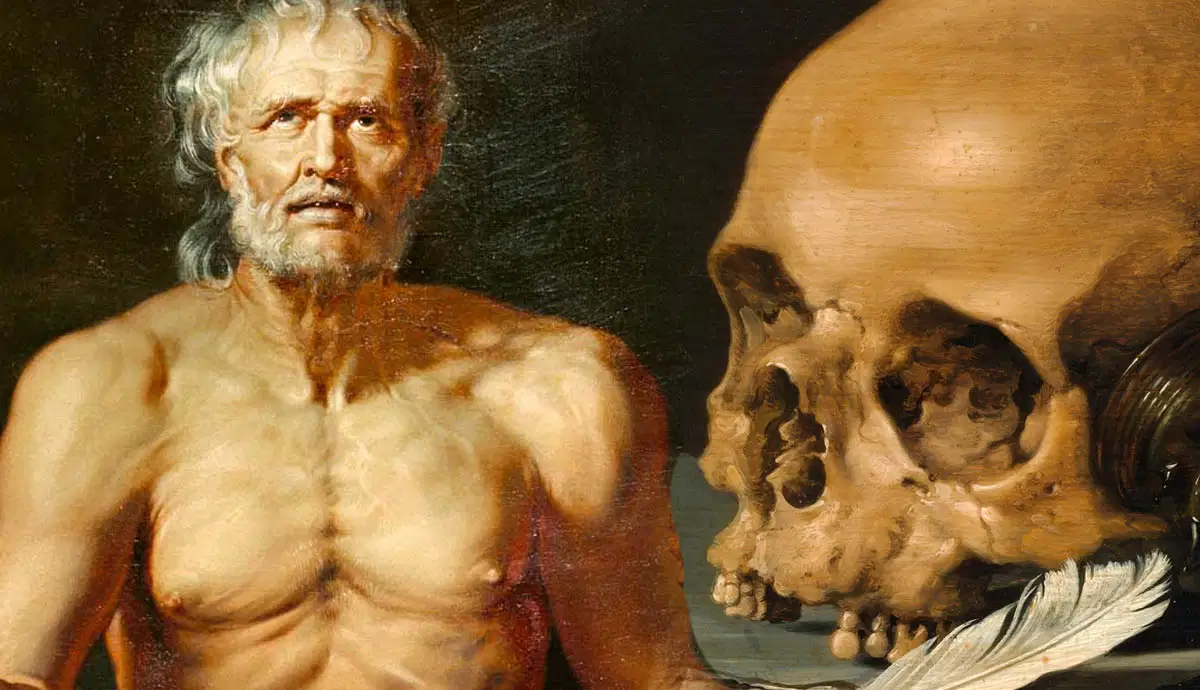

The third form of iatrogenesis discussed in Medical Nemesis is cultural iatrogenesis, that is, the destruction of traditional ways of dealing with and making sense of death, pain, suffering, and sickness. Medicine, Ivan Illich argues, has monopolized the task of managing deviance, sapping ‘the will of the people to suffer their reality.’ (Illich, 1976, p. 44).

Medicine, Illich argues, has also monopolized the task of caring for the sick, crowding out traditional ways of caring. In order for one’s deviance to be tolerated, in a medicalized society, the individual must adopt a “sick-role” and submit to medical intervention. As a consequence, traditional knowledge of self-medication is disappearing, thereby further perpetuating our dependence on institutionalized medicine.

One of the main problems with Ivan Illich’s book is that, even if Illich is right about the diagnosis of the problem, he comes up short when it comes to proposing solutions. He advocates an increase in human autonomy and responsibility for health. The problem with this is that it is exceedingly vague. Precisely what this would mean, in practice, is far from clear. That said, Illich does propose some piecemeal measures to reduce the medicalization of society.

The Medical Monopoly

One of Illich’s recommendations against the increasing medicalization of life by physicians is to enable a proliferation of healing discipline. Illich is critical of what might be termed “the medical monopoly,” i.e., the web of legal entitlements that grant exclusive licenses to practice medicine to physicians. Society, Illich argues, “has transferred to physicians the exclusive right to determine what constitutes sickness, who is or might become sick, and what shall be done to such people” (Illich, 1976, p. 6)

To counter the monopolization of power by physicians, Illich advocates the proliferation of healing practices, enabling competing groups of professionals such as chiropractors, osteopaths, acupuncturists, homeopaths, herbalists, masseurs, and yoga teachers to practice their trade.

In some sense, Illich’s recommendation has come to pass. The growth of the complementary health and wellness movements could be seen as a vindication of Illich’s argument for de-medicalizing pain, suffering, and healing. Whether this is a positive development, however, is up for question. Although some of these alternative treatments may generate real benefits, others are clear forms of quackery that, at best, generate a placebo effect.

A second measure Illich argues for is the democratization of medical technology and the enhancement of self-medication rights. The monopolization of health by medicine, Illich argues, has eroded people’s ability to self-medicate. To counter this dependence on institutional medicine, patients need to be given the freedom to purchase and use pharmaceuticals without a prescription from a doctor. Unlike his first recommendation, this has not come to pass. His argument, however, hasn’t completely disappeared from academic circles. In her book Pharmaceutical Freedom, contemporary political philosopher and bioethicist Jessica Flanagan, for example, argues that respect for people requires abolishing prescription requirements and granting individuals rights to self-medicate.

Ivan Illich’s Solutions: Fixing the Social Determinants of Health

Illich’s more prescient recommendation, however, is his advocacy for a greater focus on what has come to be known as the social determinants of health. Although decreases in mortality and morbidity are generally attributed to modern medicine, this isn’t, in fact, the case. Our social environment plays, by far, a greater role.

By the time tuberculosis was well understood, for example, it was already less virulent and had been reduced due to improvements in sanitation, housing, and nutrition (Illich, 1976, p. 6). Or, to give another example: epidemiologist John Snow put an end to the 1854 cholera epidemic in Soho, London, by disabling a water pump in Broad Street, not by using medication or treating the infected.

From examples such as these, Illich concludes that:

“Food, water, and air, in correlation with the level of sociopolitical equality and the cultural mechanisms that make it possible to keep the population stable, play the decisive role in determining how healthy grown-ups feel and at what age adults tend to die.”

(Illich, 1976, p. 20)

This focus on the social determinants of health has since been taken up by political philosopher and bioethicist Norman Daniels, a former student of John Rawls. In his Boston Review article “Social Justice is Good for Our Health,” Daniels and colleagues argue that the social conditions under which we live influence how healthy we are. Countries with greater socio-economic inequality, for example, also have higher levels of health inequality. Middle-income groups in highly unequal societies also fare worse than poorer groups in more equal societies. Although GDP per capita is significantly higher in the USA than in Costa Rica (a much poorer, but more equal society), health outcomes are comparable (Daniels, 2008, p. 84). In short, Inequality is bad for our health.

If we want to increase people’s health, Daniels and colleagues suggest, we should widen our focus beyond healthcare. Only focusing on healthcare is like providing an ambulance waiting at the bottom of a cliff. If we want to avoid injury, Daniels asks, wouldn’t it be better to focus on stopping people from falling off the cliff in the first place?

If we grant that stopping people from “falling” is the right way to go about health, what does this require? For starters, it would require eliminating absolute poverty, i.e., poverty that leads to people being unable to satisfy their basic needs for adequate shelter (water-proof, adequate temperature), and nutrition. Poverty alleviation, however, is unlikely to be enough. Eliminating health inequalities would also require substantial investments in social support services, enhancing political participation, and fair equality of opportunity. In short, it would require Rawlsian justice as fairness.

References:

Daniels, Norman. (2008) Just Health. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Illich, Ivan. (1976) Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health. Pantheon Books, New York.