On the Ides of March, 44BCE, Julius Caesar lay dying on the Senate floor, more than 20 stab wounds sustained to his body. Those wounds inflicted by the most venerated fathers of the state, the senators who included amongst their conspiracy close personal friends, colleagues, and allies of Caesar. The historian Suetonius tells us:

“He was stabbed with three and twenty wounds, during which time he groaned but once, and that at the first thrust, but uttered no cry; though some have said that when he Marcus Brutus fell upon him, he exclaimed: ‘What art though, too, one of them?’” [Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar, 82]

A shocking and iconic moment, not just of Roman history, but of world history had just occurred. This was the assassination of Julius Caesar.

The Shocking Assassination Of Julius Caesar

In evaluating the assassination many questions come to mind. Was it most shocking that Caesar had defeated and pardoned many of the conspirators that murdered him – forgiveness being a most un-Roman trait? Was the most shocking thing, that Caesar had been warned – practically and supernaturally – in advance of his murder? Or, was it more shocking, that amongst the conspirators were close personal friends and allies like Brutus? No, for my money, the most shocking thing is that Caesar had actually disbanded his bodyguard – voluntarily and quite deliberately – just before his assassination.

In the deadly world of Roman politics, this was an act so seemingly reckless as to defy belief. Yet this was a deliberate act by a very pragmatic politician, soldier, and genius. It was no act of ill-fated hubris; this was a Roman leader seeking to negotiate what we might call the ‘bodyguard paradox.’ When viewed through the prism of bodyguards and personal protection, the assassination of Julius Caesar takes on a fascinating and often overlooked aspect.

The Bodyguard Paradox

So, what is the bodyguard paradox? Well, it’s namely this. Roman political and public life became so violent as to require protection retinues and yet, bodyguards were themselves seen as a key facet of oppression and tyranny. To Republican Romans, a bodyguard was actually an incendiary issue that paradoxically drew criticism and danger for the employer. Deep within the Roman cultural psyche, being attended by guards could in some contexts be highly problematic. It was an afront to Republican sensibilities and it signaled several red-flag messages that would make any good Roman nervous and could make some hostile.

Guards As The Insignia Of Kings And Tyrants

Seen as the hallmark of kings and tyrants, a bodyguard was a cast-iron insignia of tyrannical oppression. This sentiment had a powerful tradition in the Graeco-Roman world:

“All these examples are contained under the same universal proposition, that one who is aiming at tyranny asks for a bodyguard.” [Aristotle Rhetoric 1.2.19]

It was a sentiment that was deeply alive in Roman consciousness and which even formed part of Rome’s very foundation story. Many of Rome’s early kings were characterized as having guards:

“Well aware that his treachery and violence might form a precedent to his own disadvantage he employed a bodyguard.” [Livy, History of Rome, 1.14]

It was a tool kings used not just for their protection but as a mechanism for the maintenance of power and the oppression of their own subjects.

Tyrannicide: A Noble Tradition

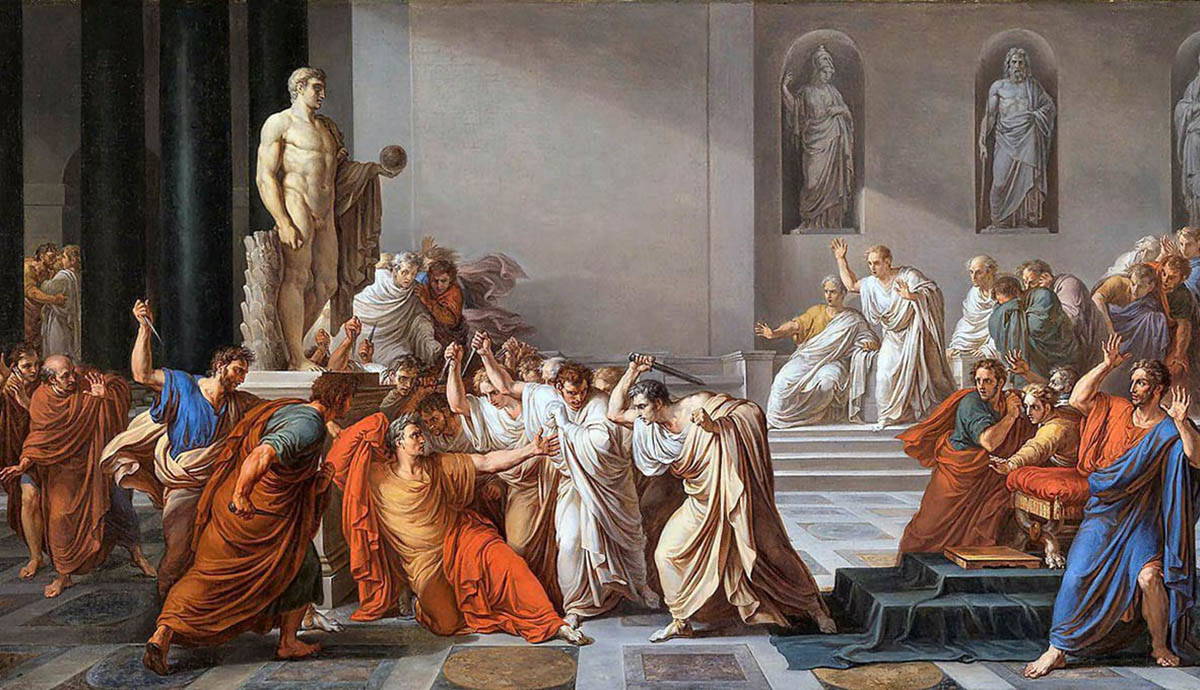

‘Julius Caesar,’ Act III, Scene 1, the Assassination by William Holmes Sullivan, 1888, via Art UK

So fed up did Romans get with the early tyranny of their kings, that they shed them off and established a Republic. It’s simply hard to overestimate the resonance that the overthrow of the kings had on the Roman psyche. Tyrannicide was to an extent celebrated, a factor still alive in Caesar’s day. Indeed, Brutus was himself celebrated as a descendant of his legendary ancestor (Lucius Junius Brutus) who had overthrown the arch tyrant and last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus. That had only been over 450 years previously. So, Romans had long memories, and resistance to tyrants was a theme that was significant in the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Bodyguards Are ‘Offensive’ In So Many Ways

Bodyguards were not only offensive to Republican values; they carried an inherently offensive capability. Then, as now, guards were not merely a defensive measure. They offered an ‘offensive’ value that was frequently used by Romans to disrupt, intimidate, and kill. Thus, could Cicero play devil’s advocate when defending his notorious client, Milo:

“What is the meaning of our retinues, what of our swords? Surely it would never be permitted to us to have them if we might never use them.” [Cicero, Pro Milone, 10]

Use them they did, and late Republican politics was dominated by acts of violence, perpetrated by the retinues and guards of Roman politicians.

Bodyguards In The Republic

Long before the assassination of Julius Caesar, the political life of the Roman Republic can be characterized as being incredibly fractious, and often violent. To counter this, individuals had increasing recourse to protection retinues. Both for their defense and to exert their political will. The use of retinues including, supporters, clients, slaves, and even gladiators was a conspicuous facet of political life. It resulted in ever more bloody consequences. Thus did two of the most notorious political rabble-rousers of the late Republic, Clodius and Milo, do pitch battle with their gangs of slaves and gladiators in the 50’s BCE. Their feud ending with the death of Clodius, struck down by a gladiator of Milo’s, a man called Birria. “For laws are silent when arms are raised …” [Cicero Pro, Milone, 11]

The adoption of a personal guard was a near essential component of any political leaders’ retinue. Before Caesar had ever started to eclipse the state, the Republic had descended into a series of bitterly contested and highly violent political crisis.’ These saw widescale blood and violence mar Roman political life. Arguably ever since, Tiberius Gracchus as Tribune of the Plebs in 133BCE was bludgeoned to death by a Senatorial mob – trying to block his popular land reforms – political violence between populist and traditional factions, become so widespread as to be commonplace. By the time of the assassination of Julius Caesar, things were no different and violence and physical danger in political life were a constant reality. Politicians utilized gangs of clients, supporters, slaves, gladiators, and eventually soldiers, to protect, intimidate, and push through political outcomes:

“For those guards which you behold in front of all the temples, although they are placed there as a protection against violence, yet they bring no aid to the orator, so that even in the forum and in the court of justice itself, although we are protected with all military and necessary defenses, yet we cannot be entirely without fear.” [Cicero, Pro Milo, 2]

Tumultuous public votes, voter suppression, intimidation, ill-natured elections, angry public meetings, and politically driven court cases, all were conducted in the full view of public life, all were politically fractious. All could be either safeguarded or disrupted by the use of personal bodyguards.

Military Guards

Triumphal Relief depicting Praetorian Guard, in the Louvre-Lens, via Brewminate

Military commanders, like Caesar, also had recourse to soldiers and were allowed bodyguards on campaign for obvious reasons. The practice of being attended by Praetorian cohorts had been evolving for some centuries in the late Republic. Caesar himself is conspicuous for not talking about a Praetorian cohort and there is no mention of Praetorians in either his Gallic or Civil War commentaries. However, he certainly had guards – several units – and there are various references of his use of picked troops that rode with him either from his favored 10th legion, or foreign horsemen that seem to have constituted his guards. Caesar was very well protected, leaving Cicero to mildly bemoan of a private visit in 45BCE:

“When he [Caesar] arrived at Philippus’ place on the evening of 18th December, the house was so thronged with soldiers that there was hardly a spare room for Caesar himself to dine in. Two thousand men no less! … Camp was pitched in the open and a guard placed on the house. … After anointing, his place was taken at dinner. … His entourage moreover were lavishly entertained in three other dining rooms. In a word, I showed I knew how to live. But my guest was not the kind of person to whom one says, ‘do call again when you are next in the neighborhood.’ Once was enough. … There you are – a visit, or should I call it a billeting …” [Cicero, letter to Atticus, 110]

However, under Republican norms, military men were not legally permitted to use troops in the domestic political sphere. Certainly, there were strict laws in place that prevented Republican commanders from bringing soldiers into the city of Rome; one of the very few exceptions being when a commander was voted a triumph. Yet, successive generations of ambitious commanders had chipped away at this orthodoxy, and by Caesar’s time, the principal had been violated on several notable occasions. Those Dictators (prior to Caesar) that did seize power in the last decades of the Republic, Marius, Cinna and Sulla, are all conspicuous for their use of bodyguards. These henchmen were used to dominate and slay opponents, usually without recourse to law.

Republican Protections

The Republican system did offer some protection for its authority in the political sphere, though this was limited. The story of the late Republic is largely the story of these protections failing and being overwhelmed. Under law, the notion of magisterial imperium and sacrosanctity (for Tribunes of the Plebs) offered protection to key offices of state, though as the brutal murder of the Tribune, Tiberius Gracchus proved, even this was no guarantee.

Respect for the Senatorial classes and the Imperium commanded by magistracies of Rome were also engrained, although practically, senior magistrates of the Republic were offered attendants in the form of lictors. This was an ancient and highly symbolic facet of the Republic with lictors themselves being partially symbolic of the power of the state. They could offer some practical protection and muscle to the office bearers they attended, though the main protection they offered was the reverence they were meant to command. While lictors attended and flanked magistrates – dispensing punishments and justice – they could not accurately be described as bodyguards.

As the febrile violence of the late Republic spilled over, there are multiple instances of lictors being manhandled, abused and over-run. Thus, did the consul Piso in 67BCE get mobbed by citizens who smashed his lictor’s fasces. On a handful of occasions, the Senate could also vote some citizens or jurors exceptional private guards, but this was incredibly infrequent and is conspicuous more for its extreme rarity than anything else. Bodyguards were too dangerous for the state to encourage and endorse. Having a bodyguard in the political sphere drew great suspicion, distrust and ultimately danger.

Julius Caesar Ascendant

Bust of Julius Caesar, 18th century, via the British Museum, London

It was against this backdrop that Caesar had eclipsed the state. Prior to the assassination of Julius Caesar, the great man had enjoyed a truly meteoric rise. Surpassing all Romans before him, SPQR, the senate and the people, and the Republic of Rome lay prostrate at the feet of his personal ambition. As a statesman, a politician and a public figure, Caesar had done it all; defeating foreign foes, crossing great oceans and mighty rivers, skirting fringes of the known world and subjugating mighty enemies. In these endeavors, he had accumulated untold personal wealth and great military power before ultimately – in a disputed impasse with his political rivals – turning that power on the state itself.

Honors, power and privilege were heaped upon him in unprecedented measure. Voted ‘Imperator for Life,’ Caesar was legally instituted as Dictator with unlimited power of imperium and the right of hereditary succession. Celebrating extensive multiple triumphs in honor of his many victories, he lavished feasts, games and monetary gifts on the people of Rome. No other Roman had achieved such unbridled dominance or such acclaim. Such was his power; few would have guessed that the assassination of Julius Caesar was looming on the horizon.

The Icarus Effect

Everything we know about the period prior to the assassination of Julius Caesar tells us that he was utterly predominant. Conferred with the title of ‘Father of the Country,’ he was awarded a gilded chair to sit upon in the Senate, symbolically emphasizing his elevation over the highest men in the state. Caesar’s decrees – past, present and future – were elevated to the status of law. Awarded a statue amongst the kings of Rome, inscribed to the ‘Invincible God,’ his person was deemed legally sacrosanct (untouchable) and the senators and magistrates took oaths that they would protect his person. He was widely hailed as ‘Jupiter Julius,’ and was transcending to the divine God among men. This was unprecedented.

Hitting upon Republican pressure points, Caesar re-organized the senate, as well as enforcing the laws of consumption on the elite classes. He even had Cleopatra – a mistrusted Eastern queen – visit him in Rome. This was all putting powerful noses out of joint. In celebrating triumphs over the Civil Wars – and thus essentially the deaths of fellow Romans – Caesar’s actions were seen by many as crass in the extreme. In two incidents in which his statue and then his person, were adorned with the laurel wreath and white ribbon of a traditional king, Caesar was forced (by an angry populace) to refute his ambitions at kingship.

“I am not King, I am Caesar.” [Appian 2.109]

Too little, too late rang the hollow protestations of Caesar. Whatever his intentions on monarchy (and historians still argue), Caesar had, as Dictator for life, stymied the aspirations of a senatorial generation. It was never going to be popular with his rivals, even those he had pardoned. He had eclipsed the state and distorted the primordial balance of Roman life. It would have to be paid for.

Disbanding Caesar’s Spanish Guard

On the eve of the assassination of Julius Caesar, we are told that he was himself forewarned of danger. The historian Appian tells us that he had therefore asked his friends to keep a watch over him:

“When they enquired if he would agree to having the Spanish cohorts as his bodyguard again, he said, ‘There is no worse fate than to be continuously protected: for that means you are in constant fear.’” [Appian, Civil Wars, 2.109]

The reference to Spanish cohorts is interesting as Caesar and his lieutenants of the Gallic wars utilized a number of foreign contingents as soldiers, personal escorts and guards. Foreign troops were widely prized as retinues by Roman leaders as they were held to be more loyal to their commanders, having little or no tie to the Roman society they operated in. Not for nothing, did the early emperors of Rome go on to employ cohorts of Germanic guardsmen, as a distinct personal retinue from their Praetorian guardsmen.

That Caesar’s disbanded guardsmen were foreign, gives us another fascinating angle on why they were potentially let go. Foreign guards were even more odious to Romans. As a symbol of oppression, no insignia could be more insulting to Roman sensibility than a foreign or indeed barbarian presence. It accentuated the notion of oppression, offending the Roman sense of freedom. This we can see clearly after Caesar’s death when his lieutenant Marc Anthony was attacked by the statesman Cicero for daring to bring a barbarian retinue of Ityreans to Rome:

“Why do you [Anthony] bring men of all nations the most barbarous, Ityreans, armed with arrows, into the forum? He says, that he does so as a guard. Is it not then better to perish a thousand times than to be unable to live in one’s own city without a guard of armed men? But believe me, there is no protection in that;—a man must be defended by the affection and good-will of his fellow-citizens, not by arms.” [Cicero, Philippics 2.112]

Cicero’s polemic powerfully conveys the afront that Romans felt for being oppressed by barbarous tribesmen. In this context, it’s not at all inconceivable that Caesar would be most sensitive about his Spanish bodyguard. Especially at a time when he was seeking to suppress hot Republican criticism and accusations about his desires of kingship.

Without Protection

Caesar Riding his Chariot, from ‘The Triumph of Caesar’ by Jacob of Strasbourg, 1504, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Julius Caesar we hear that:

“Caesar himself had no soldiers with him, because he did not like bodyguards and his escort to the senate had consisted simply of his lictors, most of the magistrates and a further large throng made up of inhabitants of the city, foreigners and numerous slaves and ex-slaves.” [Appian 2.118]

So, what was Caesar up to when he disbanded his guard? Well, it’s certain that Caesar was not stupid. He was a political pragmatist, a tough soldier and a strategic genius. He had risen up through the febrile and physically dangerous arena of Roman politics. He had stood in the maelstrom, harnessing popular and fractious policies, backed by mobs and challenged by hostile forces. He was also a soldier, a military man who knew danger; many times leading from the front and standing in the battle line. In short, Caesar knew all about risk. Could the retention of the guard have prevented the assassination of Julius Caesar? It’s impossible for us to say, but it seems very likely.

Assassination Of Julius Caesar: Conclusion

The assassination of Julius Caesar raises many fascinating questions. In truth, we will never know what was in Caesar’s mind over kingship. However, to my reckoning, he took a calculated action with his guards. Certainly not adverse to having a bodyguard, something changed that compelled him to take this deliberate and defined act. Something made him jettison his guard shortly before his death. I believe that factor was driven by the ‘bodyguard paradox,’ Caesar disbanded his foreign guards in the face of sustained criticism of his tyrannical and kingly ambitions. To do so was an expedient and calculated risk. It was a highly symbolic act in recasting his image as merely a Republican magistrate, surrounded by his traditional lictors and friends. Not the foreign guards and hallmarks of a hated tyrant. This was a calculation that Caesar ultimately got wrong and it cost him his life.

The assassination of Julius Caesar left a lasting legacy. If offered lessons that his adoptive son – Rome’s first emperor, Octavian (Augustus) – would never forget. There would be no kingship for Octavian, for him the title of ‘Princeps.’ Less jarring to Republicans, as ‘First Man of Rome’ he could avoid the criticism that Caesar attracted. But the bodyguards would stay, now an imperial guard, the Praetorian and Germanic guards becoming a permanent feature of the capital.

Later rulers were just not willing to gamble with the bodyguard paradox.