Many of us grew up hearing from teachers, parents, and other adults that there are right and wrong ways to speak. While grammar rules enable streamlined, coherent communication, the point of language—to convey an idea to another person—can be accomplished without adhering to these so closely. In fact, linguistic guidelines are due more to societal expectations than language itself, and language evolution is due largely to interactions between groups, whether that be class distinctions or centuries of colonialism. Standards for speech reflect what society at large deems important.

Prescriptivism vs. Descriptivism

There are two central viewpoints regarding language rules: prescriptivism and descriptivism. Think of prescriptivism as prescribing a correct, grammatically-focused way to speak, while descriptivism describes our actual speech in our day-to-day lives.

When entering higher education in linguistics, it becomes evident that prescriptivism doesn’t have as strong a hold as you’re taught growing up. In fact, many of these strict rules aren’t rules at all. As long as your words successfully convey your message to another person, there’s no traditional “incorrect” way to use language. We often understand this unconsciously without articulating it consciously, thus leading us to produce sentences like “where’s your party at?” to ask about a location or, in the case of emerging slang, “that’s fire” to describe something as exceptional.

Syntax consists of placements for parts of speech in order to present information, but our brains process meaning more reliably according to placement and context than mentally assigned parts of speech. That’s why an angrily muttered “you’re being such a pencil about this!” conveys meaning without a more traditionally used noun in that spot.

We rely a lot on content combined with intonation to make up meaning, so you can substitute more commonly used words for others and still get your point across. Taking this one step further, if we momentarily disregard parts of speech altogether, we could say something like, “You’re being such a get about this!” and still get at least a modicum of meaning across. While grammar rules aid meaning as per their purpose, language is strong enough to withhold its intention while stretching these guidelines.

Controversies in Language

Language has been the subject of controversies since the development of the complete sentence and will continue to spark debates long after we’re gone. Whether the concern is the different ways the younger generations utilize language or dialect variations associated with class distinctions, speakers often use language ideals to bolster arguments.

One common area of disagreement today is the use of “them” as a singular pronoun. First, it is important to remember that language is constantly evolving to suit speakers’ intentions. While this linguistic phenomenon might seem radical or new, it’s actually been in use for hundreds of years. In fact, Shakespeare has used the word “they” to refer to a singular subject before, showcasing just how much even the most prestigious language reflects the purposes of the language user. Whether for purposes of literary tension or personal preference, strict grammar rules are often disregarded to support a higher purpose—that is, the speaker’s intention.

Moreover, language use is heavily tied to identity; this is not a new idea. Particularly, it aligns us with certain social factors we may not be entirely conscious of and can even be weaponized in social disagreements.

One such example is the popular phrase “pardon my French,” which transitioned from the practice of pointing out French phrases in conversation to a means for the English to mark profanity by associating it with the French language. Now, the phrase has made its way into everyday use, fitting neatly into English’s native lexicon. A lexicon is a person or language’s complete set of meaning-making units, and it makes up the pool from which we pull our words when we speak to others.

Words or phrases that started out meaning one thing can evolve in our brains without us noticing. This happens a lot with slang. As words climb in popularity, our mental lexicons adjust to accommodate these changes, oftentimes without us consciously deciding to do so. While traditional grammar rules are connected to prescriptivism and can be rather rigid, actual speech is a fluid, ever-changing phenomenon that adjusts itself as we encounter new things. Even languages themselves can evolve outside of the original intention, like the case with constructed languages like Esperanto and Klingon, which grew far beyond what the languages’ creators could have imagined.

Origins of English Words

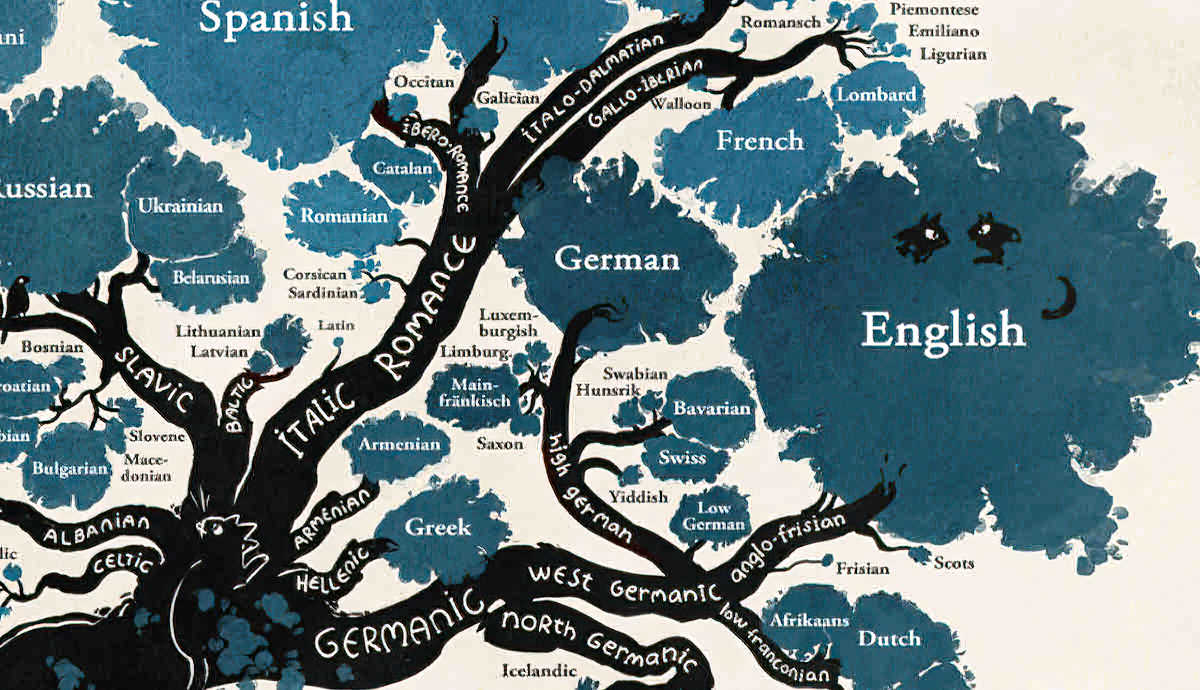

Influence from other languages and resulting changes in our own are difficult to avoid, as we are constantly in contact with those around us. Even though English is a Germanic language, about 60% of our words are borrowed from Latin. This is due, in part, to the idealization of Latin as being representative of an exceptional language and society. Not only have we borrowed root words in science and medicine, but a good portion of our casual language use stems from Latin words, like “sinister” and “nice.” A similar process happened with Greek, another language and society English borrowed words from in an attempt to emulate their assumed elite way of life. Everyday words like “academy” and “panic” are due to Greek influence.

Oftentimes, when thinking about language, it’s easy to take the patterns we notice at face value without examining how they came about. Language development is inherently linked to the development of the people who speak it. English, for example, is primarily associated with nations with long histories of colonialism. Its expansion into a lingua franca—a widespread language used to facilitate communication between a range of speakers who may not have the same native language—was originally fostered by English-speaking nations’ imperialism. For example, it is through this imperialism that English borrowed words like “poncho” and “chocolate” from Indigenous languages in the Americas.

While at one time, these borrowed words were not part of “standard” English, over time, they grew into a permanent role in native speakers’ lexicons. Now, even prescriptively, there aren’t many arguments about the appropriateness of “nice” or “chocolate” as real words, even though they did not originate as a part of English’s lexicon. As our society changes through interactions with others on a small or large scale, so too does our language.

Languages vs. Dialects

Linguist Max Weinreich, when commenting on the distinctions between languages and dialects, uttered the words, “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” There’s a common understanding that capital-L Languages are often attributed to a specific country, while dialects refer to minute variations of the common language within these countries. Weinreich’s well-known adage among linguists draws attention to the reality that these distinctions are rather trivial and that the terminology here is often used to allude to the military and social power of a country and its linguistic associations.

For instance, Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish are so similar that a speaker of one can understand the other with little difficulty. So little difficulty, in fact, that had one not been aware of their status as separate languages, they might assume these were, in fact, merely dialects. That is, after all, in line with the belief that there must be minimal differences between dialects while languages must be rather different, right? These three languages are referred to as languages for the sole purpose of aligning with their respective countries, making this distinction heavily rooted in nationality and social belonging.

African American Vernacular English

On the other hand, there are certain dialects with a vast array of differences between them that one might assume they should be attributed to separate languages entirely. One such example is the dialect African American Vernacular English (AAVE). The origins of AAVE are heavily debated, with some linguists attributing its development to interactions between African enslaved people and the British English of indentured servants, and other linguists supporting the theory that AAVE is a result of the blending of English and several West African languages.

Many of today’s English speakers hold tight to the idea that AAVE represents an incorrect and lazy way of speaking that hints at associations with lower socioeconomic status. This presumption, of course, can be extremely damaging to the communities that speak this dialect. It’s not a new ideology either, as language can be used as a tool to exercise power over another group. English has a long history of this, including but not limited to school systems banning the use of native languages in schools to increase assimilation and reinforce the association of speaking “standard” English with being intelligent, productive members of society.

African American Vernacular English has specific rules and guidelines for speech that are different from what’s perceived to be “standard” English (and what’s really standard, anyway?) that speakers of other dialects assume it must be incorrect English. Speakers of other English dialects hear linguistic phenomena such as habitual be and double negation and believe as a gut response that these are merely mistakes and not structures of language. Because these linguistic patterns are automatically assumed by speakers of other dialects to be incorrect English, people often consciously or unconsciously link this style of speech with socioeconomic status, education, and other social factors, often reflecting poorly on those who speak AAVE.

This, again, harkens back to the discussion of prescriptivism versus descriptivism. Speakers of “standard” English can hold prescriptive grammar ideals in such high regard that other dialects that don’t follow the same rules are deemed prescriptive failures. AAVE, however, has its own set of prescriptive and descriptive rules. Habitual be (for example: “he be late for school”) is not merely keeping the infinitive in the place of any conjugated version of “be.” The term “habitual” means exactly that – the use of “be” is applied to represent recurring habits. Saying “he be late for school” implies the subject is late repeatedly, and to apply habitual be to a single occurrence would break prescriptive grammar rules.

The opinion of many proponents of a single “standard” English that AAVE is grammatically and prescriptively incorrect ignores the specific rules and guidelines that make AAVE its own dialect. What may seem grammatically incorrect from a certain lens doesn’t actually hinder communication at all, and in many ways, it fosters communication and community belonging.

Popularization of Prescriptively “Incorrect” Language

Language is ever-changing, reflective of evolving trends or borrowed words. Certain aspects of dialects deemed linguistically lacking are at the same time utilized in mainstream speech by non-native speakers of those dialects. There’s been an increase in the use of African American Vernacular English outside of those communities, prevalent as slang or the popularization of alternate methods of speaking. Habitual be and other AAVE characteristics are being used in mainstream “standard” English as a form of emerging colloquial English.

This is where clinging to prescriptive grammar rules as the pinnacle of language can be harmful. Casual speakers who utilize some popularized words and phrases of AAVE are admonished for being playfully grammatically incorrect as they follow linguistic trends but are not otherwise alienated. On the other hand, native AAVE speakers are devalued for their apparent utilization of “broken” English. Grammar rules, while useful in school for growing minds, can be used as a means of consciously or unconsciously furthering certain social or political mindsets.

In instances like these, the debate between prescriptivism and descriptivism can be used to criticize certain grammar patterns as incorrect when used by some groups while bypassing disapproval for these same grammar patterns when used by other groups. Prescriptivism is bypassed in order to commodify the language of minorities into different social circles, emphasizing just how much grammar does not govern language to the extent that social expectations do.

Language, as it’s so heavily tied to identity, is a constant broadcast that tells others who we are and where we’re from. Conveying an idea to another person is always nuanced, weighed down by layers of interacting identities. Even the grammar rules you stick to are subject to this perusal. Language functions as it’s meant to, fostering the exchange of ideas even if strict rules are bent or broken. The vast majority of linguistic patterns are a direct result of either power dynamics or social commentary, indicative of a long history of both good and bad interactions.

The English language is a living thing that is, first and foremost, a reflection of its speakers, just like all other languages and dialects. The heart of communication, to connect, share, and belong, can be accomplished because of or despite strict perspective rules.