The katana is often considered the soul of the samurai. How (in)accurate this statement is in regards to history is better elaborated elsewhere. Battles were not fought with swords alone; in fact, they figured in warfare much less than one might expect. Battlefields played host to plenty of other Japanese weapons.

For this list we’re focusing on native Japanese weapons; Okinawan entries like the bo or nunchaku warrant their own article.

An Introduction to Japanese Weapons: The Yari

Let’s start with the most basic weapon: the yari. A simple spear, this implement was the basis of armed peasant levies and was the main infantry weapon of the warrior class. Artisans could easily craft them and, at least for basic tactics, conscripts could easily learn.

The blade of a yari could take many forms, but the most commonly seen was the straight-bladed one. A popular variant was the jumonji-yari, a spear with a cross-shaped blade. The blade had a lengthy tang to maintain its rigidity.

The shaft of the spear was made out of hardwood and reinforced with horn and lacquer. Its length varied from one to six meters. The famous daimyo Oda Nobunaga often equipped peasant ashigaru with spears, with longer shafts to help counter cavalry charges.

In infantry formations, the spear was simply a thrusting weapon. In single engagements like duels, it could also be used like a staff with piercing and cutting blows, blunt strikes with the shaft, and grappling actions.

Naginata

The naginata is the most recognizable Japanese polearm. It consists of a wooden shaft with a curved blade on the end. The blade could be forged specifically for a naginata, or a resourceful smith could recycle a sword blade. The naginata was used as a counter to cavalry because of its length and the weight of the blade. A skilled user could pull a rider from his horse with this Japanese weapon, cutting the horse’s legs, or simply using blunt force blows.

Techniques for using this weapon involved wide-sweeping cuts, thrusts, and strikes with the weighted pommel end. If you have the opportunity to see naginata kata (forms), you might notice some spinning of the body following intercepted strikes. Normally this is a poor choice, but the length of the weapon keeps enemies at bay. Spinning — especially because it’s done at a distance — lets the fighter check their surroundings.

Starting in the Sengoku period, the yari replaced the naginata as the main Japanese weapon for infantry. Formations were tighter and the broad sweeping motions of the naginata were impractical. The weapon was relegated to the wives of samurai to defend their homes while their husbands were away and they were often part of a woman’s dowry.

Nagamaki

The nagamaki is half-sword, half-polearm. It consists of a sword blade with an elongated hilt so that the ratio is 1:1. The word literally means “long wrap” because the hilt of the nagamaki was wrapped in the same fashion as a sword. The main difference between this Japanese weapon and a naginata is the length. It is shorter, and therefore easier to wield at close quarters. Also, there is no switching of the grip. In naginata combat, the user has to switch which hand is forward on each side. With a nagamaki, the right hand is always forward.

Because of the extra length to the hilt, the point of balance is farther back. Therefore, most of the cuts were horizontal or diagonal blows that capitalized on hip rotation rather than arm movement. At the apex of the cut, the wielder could allow the weapon to slide forward in the right hand as if swinging an ax or sledgehammer.

Cutting Through Samurai Armor: The Kanabo

Samurai armor isn’t as durable as European plate, but it still offered at least some protection against blades and arrows. The kanabo is a weapon developed specifically to defeat this armor; the Japanese answer to the warhammer or mace. Both one and two-handed variants existed.

It is a large, thick wooden club that sometimes has metal studs, spikes, or nails attached to it. Blunt force trauma inflicted by this Japanese weapon can break armor, shatter bones, and rupture internal organs. Japanese myths and legends often depict oni, or demons, wielding especially large variants of the kanabo. When coupled with the fearsome helmet designs used by samurai, the effect could be devastating, especially to a rank of ashigaru.

O-dachi

Although the sword was usually not a primary weapon on a medieval battlefield, the o-dachi/nodachi is an exception. The word means “great sword”. This imposing Japanese weapon is a scaled-up version of a katana. Just like the zweihander or claymore, it was used by elite soldiers in battle to break pike formations, or could be used as a cavalry weapon.

The o-dachi can be up to 1 meter in blade length — a third longer than the katana. It is difficult to wield effectively due to its size, but those few that mastered this weapon were formidable fighters. Today, most o-dachi rest in Shinto shrines as offerings.

Ono

Although comparatively rare, some Japanese soldiers would use ono, also called a masakari. This is a war ax with a heavy blade on each side. Like its European counterpart, it could be effective against an armored enemy through blunt trauma alone.

This weapon was rare because it tended toward overbalancing. There is supposed to be some measure of control even though the momentum is in the ax head. Also, part of the samurai cultural mindset was control and balance. A weapon that created an unbalanced stance was to be avoided. Peasant levies could sometimes fight using ono. This weapon, while not easy to use, required less technique than a lighter blade.

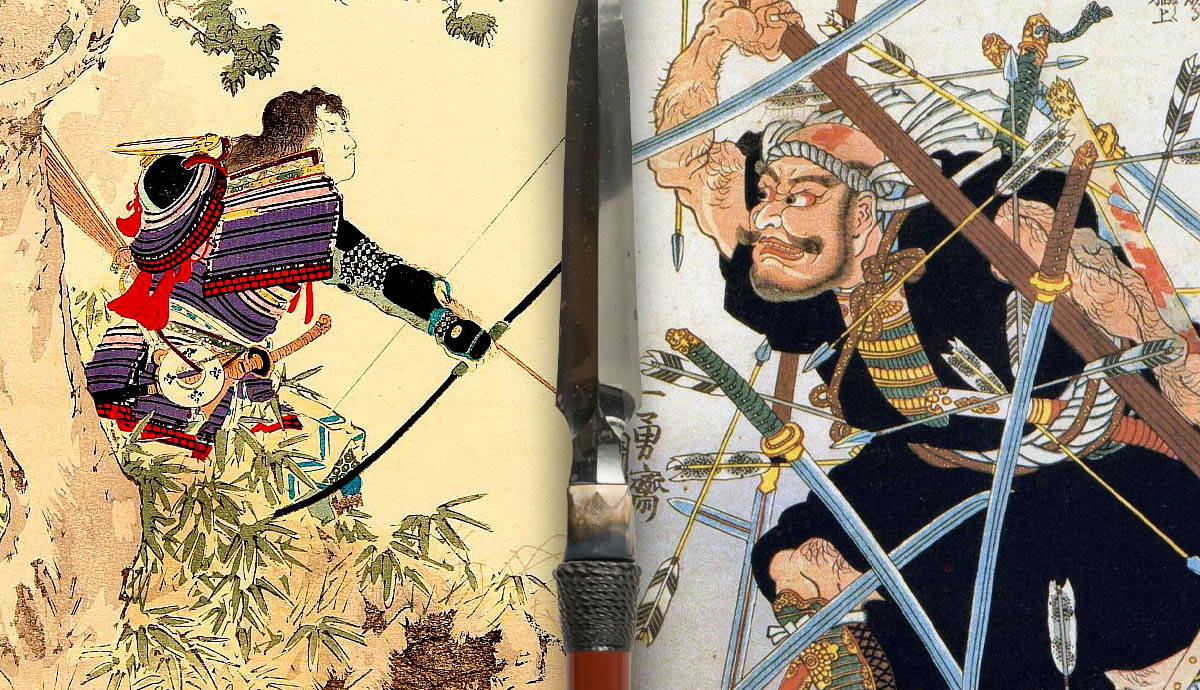

Yumi

For centuries before the Edo period, samurai fought first with bows, often on horseback. The yumi is a bow with an asymmetrical grip suited for changing sides on horseback or shooting from a kneeling posture. It is made of bamboo, yew, and backed with leather, while the string was made with horsehair or deer sinew. Modern yumi use synthetic fibers. Arrows were made of bamboo and had a variety of shapes for arrowheads.

For example, some crescent-shaped arrowheads were intended to cut rope, others were hollow cylinders, that produced a whistling sound to frighten enemies. Still others were wrapped with flammable cloth to ignite fires near a target. The yumi is one of three Japanese weapons whose use is still commonly taught as an extracurricular activity, albeit in a sporting context rather than fully martial. The other two are the katana in the form of kendo and the naginata.

Tanegashima

You might not associate samurai with firearms, but Sengoku-period Japan was far from a gentle setting. Concepts of honor had little place on the battlefield insofar as they existed. The samurai, especially those serving Oda Nobunaga, had no reservations about using firearms.

The tanegashima gets its name from the island upon which a Portuguese vessel crashed in 1543. This vessel, among other things, carried a shipment of matchlock rifles. These were primitive firearms that, while powerful for their time and certainly capable of penetrating armor, were unreliable — it took up to a minute to load and fire a single round. They were also inaccurate because of the lack of rifling in the bore of the gun.

Because of this, tanegashima were used as a mass fire weapon. The foremost rank of soldiers would fire a volley into an oncoming formation, then immediately fall back to reload. The second rank would step forward, fire, and retreat, by which time the first rank would have reloaded. In this way, this Japanese weapons could be one of the most devastating forces on the battlefield.

Ozutsu

The ozutsu (lit. “large pipe”) was one of several variants of artillery. It was a primitive cannon that was mounted on a swivel. It could be used as a weapon against infantry or mounted on castle walls as an anti-siege weapon. Some handheld variants also existed.

The ozutsu was a refined form of the crude hand cannons called teppo. The cannon could be mounted on trunnions, allowing the crew to readily adjust elevation. By the time these Japanese weapons were developed, the Sengoku period was drawing to a close. Once Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan, no large-scale battles took place for the next 260 years in the lead-up to the Meiji Restoration.

Japanese Weapons: Some Other Considerations

If you pick out a selection of Japanese weapons and put them next to their Western counterparts, the Japanese selection will look like minor variations on the same designs, whereas the other group will have much greater variation. The various blades of Europe have different blade profiles designed for use in different situations. The Japanese, meanwhile, found a design and stuck with it for hundreds of years.

The reason is practicality. Japan has very poor iron deposits, and what little could be made into steel had to be used carefully. The bladesmiths of ancient Japan found the design/forge method for a blade that worked for their needs and kept it. There was no real need to change. The blades on many Japanese weapons at least superficially resemble that of a katana.

There is also a comparative lack of shields in the samurai arsenal. Contrary to popular perception, it had nothing to do with a code of honor. All the battlefield weapons were two-handed, so shield work would have been impossible.

There were tate, stationary shields, behind which samurai would shelter as protection against arrow, musket, or artillery fire, but nothing portable. The sode, or shoulder armor, of the classic o-yoroi could serve this purpose on a makeshift basis if the wearer positioned himself correctly, but this use was rare.