Beginning around 1070 BCE, ancient Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period is one of the civilization’s most mysterious and least understood. Ushered in by the collapse of the New Kingdom, it was characterized by political instability, foreign rule, and mass immigration. Although often viewed as a dark period of chaos and decline, it birthed a specific religious development that increased in prominence throughout the first millennium BCE: the worship of Isis and Horus as divine mother and child.

Osiris, Isis, and Horus: A Divine Family Divided

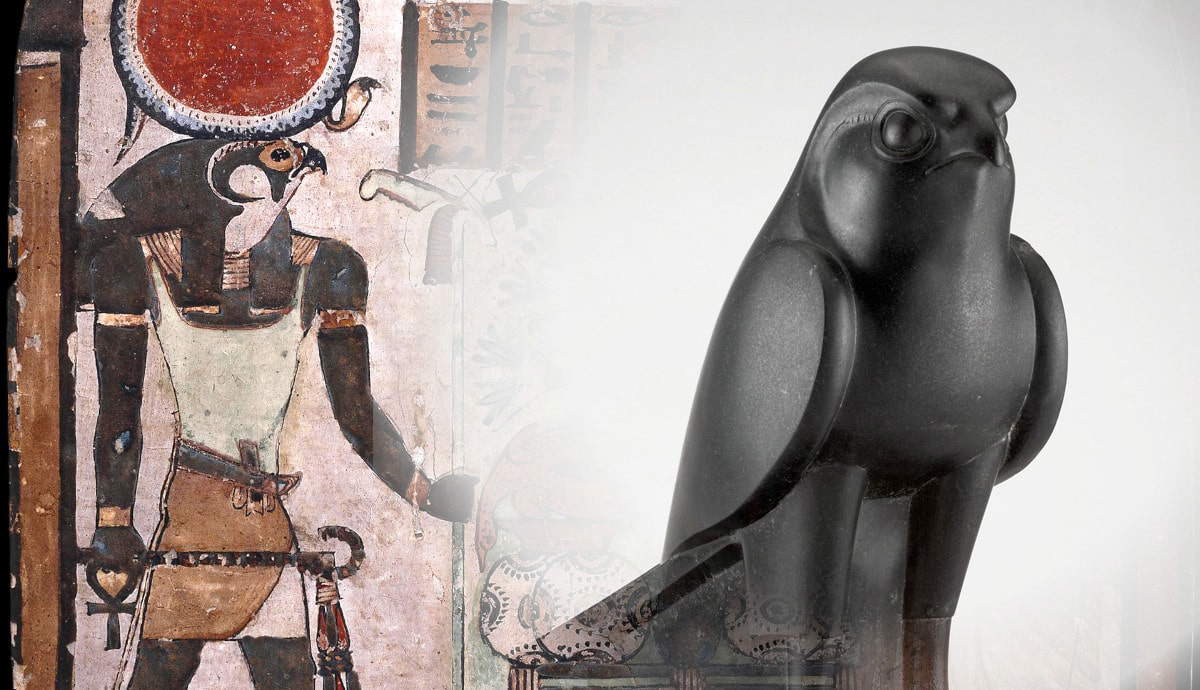

The father Osiris, the mother Isis, and the son Horus were three of the most important and revered divinities in the ancient Egyptian pantheon. Their mythological story was closely connected to kingship. To the people, the country’s ruler (or pharaoh) represented a terrestrial version of the god Horus. Osiris was known as the king of the afterlife, with whom the pharaohs, and later others, became identified after death. Isis was cherished as a magical and compassionate protector goddess. Collectively, they formed a family unit known as the Osirian Triad.

During the Third Intermediate Period (1070-664 BCE), which comprised Dynasties 21-25, the worship of Isis and Horus became somewhat detached from the triad. In addition to still being venerated as individual entities and as members of their larger family unit, they were also often depicted as a mother-and-child pair, without Osiris.

Before the start of the 21st Dynasty, there was no large-scale focus on the worship of their mother-child relationship or related themes. They only received significant attention and exposure later, becoming more noticeable during the Libyan-ruled 22nd to 24th Dynasties. Was it just a coincidence that this followed the influx and rise to power of a group of nomadic peoples from beyond Egypt’s western border?

Who Were the Ancient Libyans?

When used in reference to the ancient world, “Libyans” is an all-encompassing term that denotes the various nomadic subgroups and tribes that lived to Egypt’s west. Of the many foreigners to come into contact with Egypt throughout the civilization’s history, the Libyans were some of the most enigmatic. Their culture is poorly known, but Egyptian records of military campaigns indicate a long history of conflict with Egypt that spanned centuries. The New Kingdom brought increasingly frequent interaction between the Libyans and the Egyptians. It was during this time that the first permanent Libyan settlements likely arose within Egypt.

After gaining a stable foothold, descendants of some of these people would go on to attain positions of great power and influence in Egypt, culminating in the formation of several lines of pharaohs with Libyan origins. The kings of the first Libyan dynasty (Dynasty 22) traced their lineage back to the Meshwesh, a subgroup that had developed at least one settlement in a northern area of the country known as the Delta (Kitchen, 1990; Leahy, 1985). It is here that the Nile River branches out on its way to the Mediterranean Sea, resulting in a rich, fertile environment suitable for agriculture and fishing. It also may have provided the setting for a key mythological substory that reveals the main elements and themes of Isis and Horus’ relationship as mother and child (Gardiner, 1944).

Isis and Horus in Chemmis

In Osirian mythology, the god-king Osiris was murdered by his brother Seth, who went on to rule. After gathering the remains of her vanquished husband, Isis gave birth to Horus, the rightful heir, who would avenge the death of his father and restore order to Egypt. The overarching story has several episodes. One concerns the nurture and protection of young Horus in an area of delta-like marshland known as “Chemmis.” Horus would not be able to challenge Seth for the throne and re-establish the legitimacy of rule until he was older and strong enough. It was Isis’ job to ensure he reached maturity so he could do that.

Without her husband and aware that Seth would view Horus as a threat, Isis hid her vulnerable infant son amid the reeds and plants of Chemmis. There, she tried to keep him safe. This youthful version of Horus usually goes by the distinctive Greek name of Harpocrates, which means “Horus the child.”

Images of child-like god-kings became more common in artwork during the Third Intermediate Period in general. In the reconstructed chalice pictured above, a young god-king is shown seated, surrounded by marshland. Although this particular youth may not represent Horus specifically, the chalice is shaped like a blue lotus, a flower that grew in abundance in the Delta, where Isis sought refuge.

Isis and Horus in Art and Iconography

Several other kinds of artifacts that depict Horus the child and his mother became more prominent at the onset of the Third Intermediate Period. One of the most common are small statues made from stone, wood, or metal that show an infant Horus sitting on Isis’ lap (Fazzini, 1988). These statuettes were particularly prevalent in the Late Period (Dynasties 26-30) but also existed during the Libyan dynasties.

Although the material they were sculpted from varies, the scene they depict is the same. Isis (enthroned) is portrayed as a caring and devoted parent, suckling her divine child as she rears him to adulthood.

Similar iconography appeared on spacer beads from the period. Openwork spacers are small, rectangular decorative items that were used as beads on bracelets. They emerged at the end of the New Kingdom and also show young gods in the protective confines of marshes. In the example above, we can see Isis and Horus (Tait, 1963) in a pose that matches that of the statuettes. They are surrounded by papyrus plants. The other side of the same spacer bead contains an image of the heir to the throne crouched on top of a lotus flower.

Objects like these not only highlight the mythological importance of the marshes as a place of sanctuary for Isis and Horus the child. They also hint at the protective and regenerative properties with which the mother-and-son pair were identified. As their Chemmis substory and associated themes became more pervasive throughout the first millennium BCE, they functioned as key components of magical amulets and became part of medicinal practices.

Isis and Horus as Protectors and Healers

In ancient Egypt, many symbols and amulets were associated with the supernatural powers of Isis and adult Horus. However, the archaeological record reveals that from around the end of the New Kingdom, a special type of magical artifact that featured Harpocrates gained popularity. These amulets or stelae of Horus the child are called cippi, and their function and decoration are also connected to the Chemmis myth.

During his upbringing in the marshes, young Horus was stung by a scorpion and subsequently died. With the help of the god Thoth, Isis brought her son back to life, and because of this, he came to possess protective power over noxious and dangerous animals. Cippi were used as tools to ward off harmful creatures and to help heal people from snake bites and scorpion stings. They contained magical inscriptions over which water was poured (Seele, 1946). Attack victims probably drank or applied this sacred water in the hope it would aid their recovery.

The decoration on these artifacts correlates with their function. A naked Harpocrates holds on to hazardous wildlife as he tramples crocodiles beneath his feet. Some cippi also depict additional scenes that represent the protection Isis gave to Horus in the swamplands of Chemmis. Although most common from the 26th Dynasty, earlier examples indicate the growth of Isis and Horus the child’s mythological themes during the Third Intermediate Period.

What’s in a Name?

Harpocrates isn’t the only name that signifies the prominence of Isis and Horus’ mother-and-child themes during this era. In addition to their personal names (the names that historians use to refer to them), ancient Egyptian pharaohs also had a series of honorific titles and descriptive names called epithets. One scholar points out that the epithet “son of Isis” often appears in the royal titulary of the Third Intermediate Period (Muhs, 1998). Several kings of the Libyan 22nd and 23rd Dynasties employed it, demonstrating that they intentionally portrayed themselves as sons of the divine mother. This is supported by the fact that the personal name of one 22nd Dynasty ruler (Harsiese) means “Horus son of Isis.”

The name Isetemkheb, meaning “Isis is in Chemmis,” is another personal name that appears frequently in the first millennium BCE. It belonged to a number of royal women (Kitchen, 1973). One Egyptologist traced the name’s development and deduced that it did not appear as a personal name before the end of the New Kingdom (Seele, 1946). Names alluding to the mother-and-child themes of Isis and Horus are also apparent elsewhere.

Donation stelae, like the one pictured above, show the names of temples, gods, and goddesses that were presented with gifts. One expert who made a comprehensive study of these monumental records noted the names of the receiving deities (Meeks, 1979). His work reveals that several donations were made to Harpocrates and Isis of Chemmis. Although these stelae were rare before the 22nd Dynasty, they further highlight the pervasiveness of the mother-and-child thematic worship of Horus and Isis in the Libyan era.

The Libyan Link

Shrouded in darkness and mystery, the history of the nomadic Libyan migrants whose descendants went on to rule Egypt is still not fully understood. From the vulnerability of their initial New Kingdom settlements, they gradually gained strength and influence as they climbed the social strata of Egypt until they sat on the throne. That the increased popularity of the divine mother-and-child mythological themes of Isis and Horus parallels the Libyans’ rise to power suggests a close connection. But for what reason?

While there is no single widely accepted explanation for the phenomenon, there are some interesting possibilities. The scant evidence available hints that the ancient Libyans may have placed special emphasis on the concept of immediate family, the idea of succession, and the roles of women. If true, the mythology of Osiris, Isis, and the young Horus might have provided a relatable cultural anchor for them in their new home. As the setting of the Chemmis tale mirrored the physical environment of their own Delta settlements, it would have been particularly easy to identify with.

One scholar has suggested that the Libyans might have originally had the aim of setting up a “nomadic state” in Egypt (O’Connor, 1990). Another has pointed out that their use of existing iconography might have been beneficial to them by making it easier for Egyptians to accommodate the rule of foreigners (Leahy, 1985). Did they strategically link themselves to an element of established mythology to capitalize on the country’s instability?

A Lasting Legacy

The reasons and motivations for Libyan settlement in Egypt are unclear. Some may have initially been prisoners of war, but their growth and ascension demonstrate similarities to young Horus’ evolution in Chemmis. With Isis’ protection, he survived in the Delta marshland until he became old and strong enough to stake his claim to rule the country. After taking root at the start of the Third Intermediate Period, the pair’s adoration as divine mother and child also developed and matured.

The veneration of the mother and child was prevalent through the Late Period and into Greco-Roman times. Their mythology continued to manifest in art and even became visible in architecture. Some people have hypothesized that later representations of Isis and her infant son may have influenced the traditional Christian imagery of Mary and baby Jesus. Whether true or not, such theories offer us a thought-provoking reminder of the interplay that occurs when different cultures converge.

Consideration of ancient historical developments like this one raises questions that are still relevant today. More people live abroad now than at any other time in human history. What beliefs do they carry with them when they emigrate? How do they adapt existing ideas and customs to forge new identities for themselves in a different land? How do they affect long-term change in the societies they live in?

Bibliography

- Fazzini, R. A. (1988). Iconography of Religions XVI, Egypt Dynasty XXII-XXV. E. J Brill.

- Gardiner, A. H. (1944). Horus the Behdetite. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 30. Egypt Exploration Society, 23-61.

- Kitchen, K. A. (1990). The Arrival of the Libyans in Late New Kingdom Egypt. In Leahy, A. (ed.), Libya & Egypt c.1300–750 BCE. SOAS, CNMES & SLS, 15-27.

- Leahy, A. (1985). The Libyan Period in Egypt: An Essay in Interpretation. Libyan Studies 16, 51-65.

- Meeks, D. (1979). Les Donations aux Temples dans l’Égypte du Ier Millénaire avant J-C. In Lipinski, E. (ed.), State and Temple Economy in the Ancient Near East II. Orientaliste, 605-687.

- Muhs, B. (1998). Partisan Royal Epithets in the Late Third Intermediate Period and the Dynastic Affiliations of Pedubast I & Iuput II. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 84. Egypt Exploration Society, 220-223.

- O’Connor, D. (1990). The Nature of Tjemhu (Libyan) Society in the Later New Kingdom. In Leahy, A. (ed.), Libya & Egypt c.1300–750 BCE. SOAS, CNMES & SLS, 29-115.

- Seele, K. (1946). Oriental Institute Museum Notes. Horus on the Crocodiles. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 6. Cambridge University Press, 43-52.

- Tait, G. A. D. (1963). The Egyptian Relief Chalice. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 49. Egypt Exploration Society, 93-139.