Louis Althusser was one of the most influential political thinkers of the 20th century. One of his most notorious contributions was the critical analysis of ideology, its role in the state, and the relationship between ideology and subjects. In this article, we will explore Althusser’s notion of ideology and, more specifically, the way it relates to the freedom of individuals in society.

What is Ideology for Louis Althusser?

It is not unusual to hear the term “ideology” (or “ideological”) being used to criticize or disapprove of an individual’s or group’s beliefs. A quick search of the term on CNN’s news headlines returns instances in which “ideology” is in the vicinity of words like “terror,” “radical,” “extremists,” “fascist,” and so on. A similar search in Fox News provides also headlines with other negative connotations but from a different political spectrum (e.g., “woke”).

It seems, as Terry Eagleton put it, that “Ideology, like halitosis, is in this sense what the other person has” (1991, p. 2). But broader notions of Ideology can be given, like that offered by Professor Michael Freeden, according to which we “produce, disseminate, and consume ideologies all our lives” (2003, p. 1).

It is impossible to define ideology once and for all because there are many meanings to it, and each of them can be useful in its own respect. Instead, the focus here will be on the way Louis Althusser conceived the concept of ideology and the impact that his position has on subjectivity. The question “how free our we?”, then, is limited to its relationship to ideology and subjectivity.

Anyone familiar with Louis Althusser’s writings quickly realizes that the above question is still too vague. Which entry point would be the most appropriate to tackle the concept of ideology according to one of the most relevant Marxist philosophers?

Throughout his life, Althusser authored plenty of books and essays, ranging from his interpretations of The Capital by Marx (1965) to his analysis of Machiavelli’s political thought in Machiavelli and Us (1998). He also discussed many philosophical areas, like hermeneutics, epistemology, philosophy of science, and aesthetics (Lewis, 2022). Furthermore, his own life is connected to all these intellectual elaborations: his experiences as a prisoner in World War II and the sad turn in the latter stage of his life dealing with depression and his psychiatric hospitalizations. We will explore our original question, namely the one concerning freedom, by focusing only on his essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” published in 1970.

How should the problem of subjectivity and freedom be framed? Althusser tackles the ambiguity within the term “subject;” he writes:

“In the ordinary use of the term, subject in fact means: (1) a free subjectivity, a centre of initiatives, author of and responsible for its actions; (2) a subjected being, who submits to a higher authority, and is therefore stripped of all freedom (…)”

(2001, p. 182).

To grasp the contradictory relationship between these two senses of subjectivity, we begin by addressing Althusser’s theory of ideology.

Marx’s and Engels’ Camera Obscura

In The German Ideology (1846) Marx and Engels used the metaphor of a camera obscura to explain ideology. The camera obscura is a device with a small hole at one side (the aperture) through which an image of the real world is projected onto a flat surface (like a wall). The image is inverted and reversed. Light travels in straight lines, so the rays of light that enter the aperture are then redirected in a straight line to the opposite side of the box, where they form an inverted image of the external scene.

In ideology, things appear upside-down. Ideology, like the camera obscura, projects a distorted and inverted image of reality onto the minds of individuals. According to Althusser, ideology for Marx and Engels is mostly a distortion of reality; it is conceived “as a pure illusion, a pure dream, i.e. as nothingness. All its reality is external to it.” (2001, p. 159).¹

Ideology, then, is constructed as a system of ideas that dominate the mind of a social group (2001, p. 158). Ideology is not neutral nor objective in its representation of reality; it is a partial view that reflects the interests of the ruling class.

Althusser agrees with the view that ideology safeguards and ensures the reproduction of a system beneficial to those in power, but he does not want to regard it as pure delusion. Ideology is not merely the “illusory contortions of a camera obscura reflecting the distorted consciousness of individual subjects, but an aspect of reality” (Freeden, 2003, p. 27). By this, he wanted to stress the materiality of ideology and its role in supporting the capitalistic structure.

Let’s formulate Althusser’s position from another perspective. He returns to the Marxist understanding of society as composed of two parts: the infrastructure and the superstructure.

Imagine a two-floor building. The infrastructure is the economic base (first floor) of society, and it includes the forces and relations of production (workers, factories). The superstructure is erected on top of the economic base on which it is dependent. Some components of the superstructure are religion, law, education, culture, etc. But the superstructure is determined by its base like the second floor is determined by the first.

Althusser explains: “the object of the metaphor of the edifice is to represent above all the ‘determination in the last instance’ by the economic base” (2001, 135). Althusser wants to depart from this determinism to highlight the materiality of ideology in reproducing and shaping the economic base. For him, the superstructure is not a passive reflection of the first floor. Ideology helps to maintain the relations of production not because they delude individuals (by not allowing them to see the infrastructure), but because it creates subjects out of individuals.

The reader should be warned here, however, that this interpretation of Marx (as reducing the superstructure to its base) has been heavily criticized; Marx was more than aware of the dialectical relationship between the two (Jessop & Sum, 2018).

Repressive and Ideological State-Apparatuses

To summarize, Althusser is interested in the way a social order reproduces itself to persist in time (2001, pp. 129-133). In his view, the reproduction of the social order takes place not only at the economic base (infrastructure) but also in the superstructure where ideology is found. Ideology is more than just a distortion of reality; it has a material effect. But what is the mechanism through which ideology accomplishes the reproduction of the system?

Althusser divides the state apparatuses according to their repressive and ideological characters. The Repressive State Apparatus (RSA) secures the reproduction of the relations of exploitation by force: “from the most brutal physical force, via mere administrative commands and interdictions, to open and tacit censorship” (2001, p. 150). The police, the military, the courts, the government, and prisons belong to RSA. It is sufficient to look at any social movement of civil protest to witness the activation of the RSA. Although these institutions require ideology (to ensure their cohesion), they function primarily by repression (2001, p. 145).

In contrast, the Ideological State Apparatus (ISA) does not work with violence. Instead, as Rehman notes, the “specificity of the ideological state apparatus is the fact that they ‘predominantly’ aim at the voluntary subjection of those addressed” (2013, p. 150).

For the French theorist, the most important ISA is education. Education has replaced the church in its functions, and the powerful church-family dyad has now transformed into the school-family dyad (2001, p. 154). For him, it is mostly in schools that individuals become subjects; there, instruction and knowledge are “wrapped in the ruling ideology”—be it in natural history, or arithmetic, or more directly through ethics, philosophy, and civic instruction (2001, p. 155).

Fans of Pink Floyd could relate the above to the lyrics of Another Brick in The Wall (1979) and the signing voices of students: “We don’t need no education, we don’t need no thought control, no dark sarcasm in the classroom, teachers, leave them kids alone.” In their music video, one can see how students are oppressed and the way they, in the end, rebel against the whole institution.

It is a useful image to relate to Althusser’s notion of the ISA, but the point made by Althusser is subtler: it is when education seems freer and unrelated to ideology (like when learning about biology or literature) that it creeps in. Ideology makes things obvious and natural, and in that sense, they try to escape contestability (2001, p. 172). There is no need for violence; that kind of power is for the RSA. To repeat, the ruling ideology is realized in the ideological state apparatuses. Through them, the reproduction of the system is ensured.

Ideological Interpellation

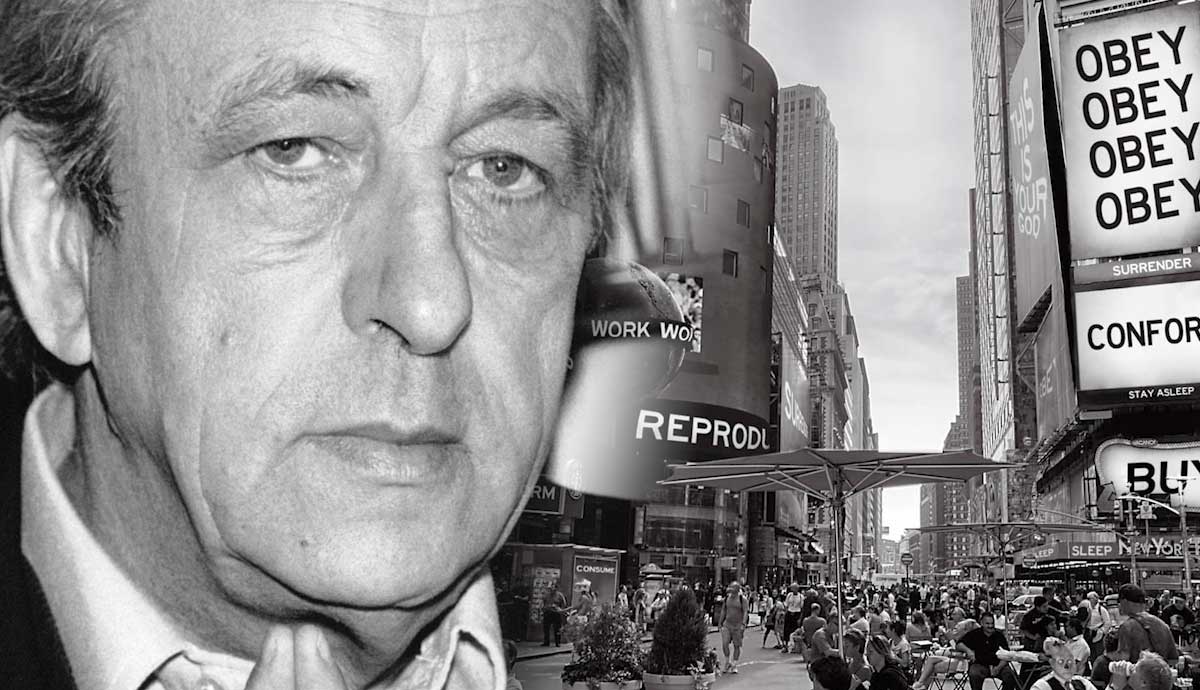

Ideology makes subjects out of individuals through various institutions. “All ideology hails or interpellated concrete individuals as concrete subjects” asserts Althusser (2001, p. 173). The process through which individuals are transformed into subjects is named interpellation.

The paradigmatic example is that of a police officer shouting at someone on the street: “Hey, you there!” The individual turns around and becomes a subject because she has recognized herself in the calling; it was addressed to her (2001, p. 174). In interpellation, social and juridical identities are presented to the individual.

Moreover, individuals for Althusser are “always-already subjects” because even before their birth, certain subjectivities have been appointed. Expressed differently: individuals are already born into subjects (2001, p. 176). Thus, we return to the ambiguity of the term subjectivity: “(1) as free subjectivity, a centre of initiatives, author of and responsible for its actions; (2) a subjected being, who submits to a higher authority, and is therefore stripped of all freedom (…)” (2001, p. 182).

However, now Althusser can make sense of the ambiguity because the point of interpellation is to transform individuals into subjects by using their freedom. He explains, “the individual is interpellated as a (free) subject in order that he shall submit freely to the commandments of the Subject, i.e. in order that he shall (freely) accept his subjection, i.e. in order that he shall make the gestures and actions of his subjection ‘all by himself’” (2001, p. 182).

Althusser uses the Old Testament’s story of Moses and the burning bush to elaborate his point. The narration is found in Exodus chapter 3:

1 Now Moses was tending the flock of Jethro his father-in-law, the priest of Midian, and he led the flock to the far side of the wilderness and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. 2 There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. 3 So Moses thought, “I will go over and see this strange sight—why the bush does not burn up.” 4 When the Lord saw that he had gone over to look, God called to him from within the bush, “Moses! Moses!” And Moses said, “Here I am.”

(New International Version)

Althusser sees in the story of Moses an instance of interpellation in which the prophet submits to God’s authority and freely answers “Here I am.” Moses is guided by his impulses. “The subject is subjected in the form of the autonomy” (Rehmann, 2013, p. 156). God is the authority par excellence, and this recognition will lead Moses to obey him and make his people obey God’s Commandments (2001, p. 179). Therefore, the notion of interpellation sees freedom as a mechanism for subjection to a higher authority—be it God or the State.

The Limitations of Louis Althusser’s Interpellation Model

Recognizing that we have only scratched the surface of Althusser’s theory of ideology, it could be useful to underline some limitations, especially with the model of interpellation.

Rehman comments on the story of Moses as framed by the French theorists: “the actual historical superpower defining the power-field is not God, but the Egyptian state equipped with huge apparatuses, both repressive and ideological” (2013, p. 157). Indeed, God is calling on a little subject (Moses); however, the purpose is to empower him to stand up against a big Subject, the ruling powers.

God’s interpellation with the prophet is part of an act of resistance. Rehman concludes: “The real history of ideological struggles is replete with such contradictory combinations, which points to the need to ‘dialecticise’ Althusser’s model of interpellation” (2013, p. 157)

This shows that the ISAs are not necessarily reproducing the dominant ideology. Many illustrations of the ways in which religion and education have been part of resistance movements can be found: the Theology of Liberation in Latin America (e.g., Leonardo Boff) and Critical Pedagogy (e.g., Paulo Freire) were both influenced by Marxist ideas.

Many other scholars have criticized Althusser’s model of interpellation along similar lines: Stuart Hall, Judith Butler, and Terry Eagleton, for example (Rehmann, 2013, p. 157). The overall point is that individuals can respond and navigate interpellations. Moreover, there is no unique interpellation in society. Rehman writes: “Each subject is confronted with different, competing, and even opposed interpellations (…) he or she needs to balance and prioritise them, which might imply rejecting some in order to be able to ‘respond’ to others” (2013 p. 175).

Most of these observations return to the idea that we cannot forsake the premise that individuals, even if made subjects in several dimensions, remain capable of agency. Is “freedom” too large of a word to describe this kind of agency?

However deep these limitations are, Althusser’s theory of ideology and his model of interpellation continue to be relevant today. His assessment of ideology as something beyond pure illusion is significant and has influenced the thought of distinguished philosophers like Alain Badiou, Pierre Bourdieu, and Michael Foucault (Lewis, 2022). Revisiting Althusser is always worth it.

Literature

Althusser, L. (2001). Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation). In Lenin and philosophy, and other essays (pp. 127-193). Monthly Review Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). Greenwood Press.

Eagleton, T. (1991). Ideology: An introduction. Verso.

Freeden, M. (2003). Ideology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. [https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780192802811.001.0001](https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780192802811.001.0001)

Hall, S. (2006). Cultural Studies and the Centre: Some problematics and problems. In Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies, 1972-79 (pp. 2-35).

Routledge Centre for contemporary cultural studies, University of Birmingham.

Jessop, B., & Sum, N.-L. (2018). Language and critique: Some anticipations of critical discourse studies in Marx. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(4), 325-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1456945

Lewis, W. (2022). Louis Althusser. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/althusser/

Rehmann, J. (2013). Theories of ideology: The powers of alienation and subjection. Brill.

¹ This reading of Marx’s and Engels’ concept of ideology by Althusser has been criticized (Rehmann, 2013, p. 29).