Though modern biblical scholars hold that Satan is a spiritual being with no physical form, artistic renderings of the devil are abundant and vary wildly over the course of history. The prince of darkness has been repeatedly depicted as a snake, a dragon, all manner of horned beasts with cloven hooves — and, more rarely, something beautiful. “And no wonder, for Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light” (2 Corinthians 11:14).

Here are five brilliant depictions of Lucifer in art over the past 250 years.

1. Satan as the Fallen Angel by Sir Thomas Lawrence

This golden, glowing rendition of Lucifer in art is a chalk drawing by Sir Thomas Lawrence. The gorgeous illustration was inspired by Milton’s Paradise Lost and is thought to depict that scene in which Satan delivers the line that has gone down in history: “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.”

Lawrence, a British painter, began his career in childhood, drawing portraits for the patrons of his father’s inn. A self-taught prodigy, he spent only a short time as a student of the Royal Academy before being selected to paint a portrait of Queen Charlotte at Windsor Castle. He would later be named “Painter in Ordinary” for the court of King George III, though most of his work would be in service to the king’s son, the Prince Regent, due to George III’s illness.

In addition to becoming a Royal Academy member and eventually serving as the organization’s president, Lawrence would be knighted for his service to the Crown in 1815. He worked as a celebrated portrait artist for the majority of his career, and his largest project — a series of 24 full-length portraits of members of the Holy Alliance — still hangs in Windsor Castle.

Satan as the Fallen Angel is far from Lawrence’s best-known work or even his best-known portrayal of the devil. That honor goes to the massive, nine-by-fourteen-foot Satan Summoning His Legions, which debuted to lukewarm reception in 1797.

At just eight by nine inches, Satan as the Fallen Angel is diminutive by comparison but beautifully polished and altogether more radiant. The original drawing was sold at auction (along with Lawrence’s vast collection of original drawings by the likes of Michelangelo and Raphael) a few months following the artist’s death in 1830.

2. Satan in His Original Glory by William Blake

William Blake’s watercolor depiction of Lucifer before his fall from grace is just one in a series of commissioned illustrations he completed for Paradise Lost. Resplendent and celestial, Blake’s delicate 1805 portrayal reveals the beauty and perfection of the Angel Lucifer. Tiny moons and stars dance at his feet; miniature angels herald his approach. Unfortunately, the painting is also an “extreme example” of damage due to light exposure and is purported to be significantly less brilliant than it once was.

Blake’s depictions of Satan after the fall (such as Satan Arousing the Rebel Angels) are significantly more masculine: a Herculean nude lording over the souls of the damned. Later illustrations incorporated a new method of relief etching (Blake’s own invention) he called Illuminated Printing.

Though his body of work is now considered to be the epitome of Romanticism, Blake was largely discounted and even derided during his lifetime. A London native from a modest family, he struggled to make a name for himself among the wealthy cadre of artists of the day.

Blake was also something of an eccentric; he claimed to experience visions, writing and illustrating a series of 12 prophetic novels in verse based around a mythology entirely of his own making. Most of his writings were dismissed at the time, but his poem The Tyger remains one of the English language’s most recognizable for children.

3. The Fallen Angel by Alexandre Cabanel

Alexandre Cabanel was just 24 years old when he debuted L’Ange Dechu at the Paris Salon. A classically trained painter in the Academic style, Cabanel enjoyed moderate success during his years as a student, even winning a prestigious scholarship from King Louis XIV to study the works of the Old Masters in Rome.

Critics were taken aback by the 1847 submission of The Fallen Angel; while religious and mythological scenes were par for the course in mid-19th century Europe, depictions of Lucifer in art — especially in angelic form — were definitely not.

When the initial shock wore off, their assessment was less than flattering: too romantic, imprecise, inadequate. And yet the piece has inarguably gone down in history as Cabanel’s most recognizable. Likely also inspired by Paradise Lost, Cabanel lays bare a Lucifer immediately following his casting down from heaven. He is beautiful, arresting, humiliated, and defiant, a single hot tear sliding from angry, red-rimmed eyes.

Cabanel had moderate success in the decade following, but it wasn’t until 1863 that he became a household name. His Birth of Venus (painted nearly 400 years after Botticelli’s famed rendition) was a favorite of the 1863 Paris Salon. The painting, which depicts Venus reclining nude across the waves while a group of putti flits around overhead, was purchased by Napoleon III for his personal collection.

The Fallen Angel is housed at the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, France, while Birth of Venus resides in the Musée d’Orsay.

4. Le Génie du Mal (L’Ange du Mal) by Joseph and Guillaume Geefs

In 1837, St. Paul’s Cathedral in Belgium commissioned a young artist named Joseph Geefs to sculpt several statues, including one of Lucifer. The white marble statue, called The Evil Angel and later The Evil Genius, was installed in the church in 1842 — and promptly removed within the year.

The statue depicts a slim-built, young Lucifer with soft curls and a thoughtful expression, a scrap of fabric slipping down one thigh. He would be easy to confuse with any other angel, but for his bat-like, membranous wings and the serpent coiled at his feet.

Overall, the church and its parishioners found the statue to be too innocent looking, too distracting, and “too sublime.” It was removed from the church and reportedly purchased by King William II; later, the sculpture would be installed at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium.

Joseph Geefs (one of seven Geefs brothers, all of them sculptors) went on to have a successful career, exhibiting pieces to The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts up until 1859. Meanwhile, St. Paul’s commissioned one of Joseph’s older brothers, Guillaume, to sculpt a replacement for the statue of Lucifer. They may have gotten more than they bargained for.

Guillaume returned in 1848 with an even more striking, more magnificent rendition of the devil. His Lucifer is imposing: powerful in form and tortured in expression, with small horns emerging from his swept-back hair. He is also — importantly, for the church — defeated.

His head is down, his right ankle shackled like Prometheus. Near his taloned toenails are an apple, conspicuously bitten, and a scepter topped with a star. These items bring to mind the apple that tempted Eve in the Garden of Eden and a passage from Isaiah: “How you have fallen from heaven, O morning star, son of the dawn!”.

Apparently, those in authority at the church were content with Guillaume’s work; Le Génie du Mal remains on display at St. Paul’s Cathedral in Liège, Belgium.

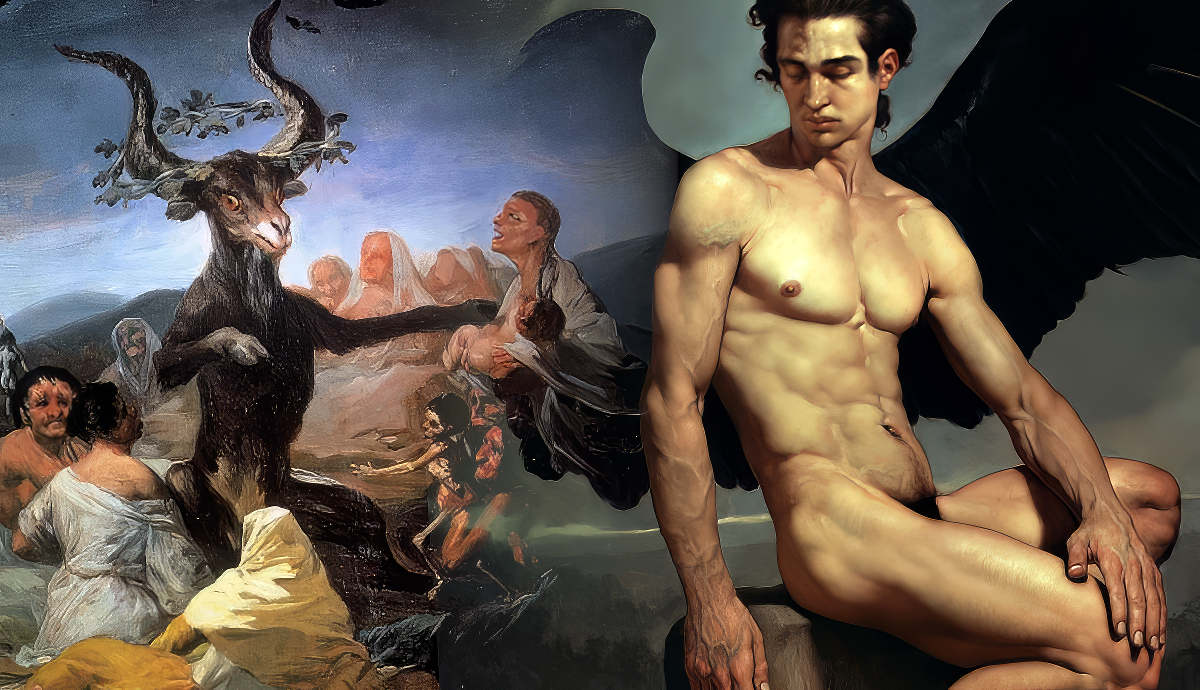

5. Lucifero by Roberto Ferri

Roberto Ferri’s paintings are a masterclass in art history. A self-taught oil painter from Italy, the contemporary artist depicts traditional Academic themes in a stark, bold neoclassical style – with a twist. Mannerist contortion is one of Ferri’s hallmarks, along with the dramatic, Baroque chiaroscuro synonymous with Caravaggio (the artist to whom he is most often compared). Ferri’s work is formidable, often explicit, occasionally shocking, and always stunning. His gorgeous renditions of Lucifer in art are no exception.

With traditionally angelic wings in an inky black and dark hair curling away from sulky, classical features, Lucifero is a perfect contrast to the archetypal angel. The painting brings to mind Guillaume Geefs’ Le Génie du Mal — Lucifer as Prometheus, his foot (blackened by gangrene in Ferri’s interpretation) chained to the stone on which he perches. But where Geefs’ Lucifer emanates defeat, Ferri’s maintains an air of nobility and pride in both posture and countenance.

Though his paintings are Academic in theory – in that they focus primarily on religious and mythological themes – Ferri pushes the envelope in practice. His 2021 painting Il Bacio di Dante e Beatrice (The Kiss of Dante and Beatrice), commissioned to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the Divine Comedy, is a perfect example.

In the poet’s real life, Beatrice was Alighieri’s muse, a childhood infatuation who died young, leaving him brokenhearted. In Dante’s Inferno, Beatrice serves as an intercessor; later, she will guide him through paradise. Beatrice is the embodiment of divine, pure, and virtuous love. The nude, passionate kiss depicted in Roberto Ferri’s painting never happened, neither in life nor in Dante’s epic poem, but is, in the words of the artist himself, “a triumph of sensuality.”