Wittgenstein’s writings represent one of the most difficult corpora of texts in the history of philosophy to interpret. At one time, his ideas were generally misunderstood and distorted even by those who called themselves his students. He doubted that he would be better understood in the future. The Philosophical Investigations are the crowning achievement of his career and remain a source of inspiration and controversy for philosophers working today.

What Are the Philosophical Investigations?

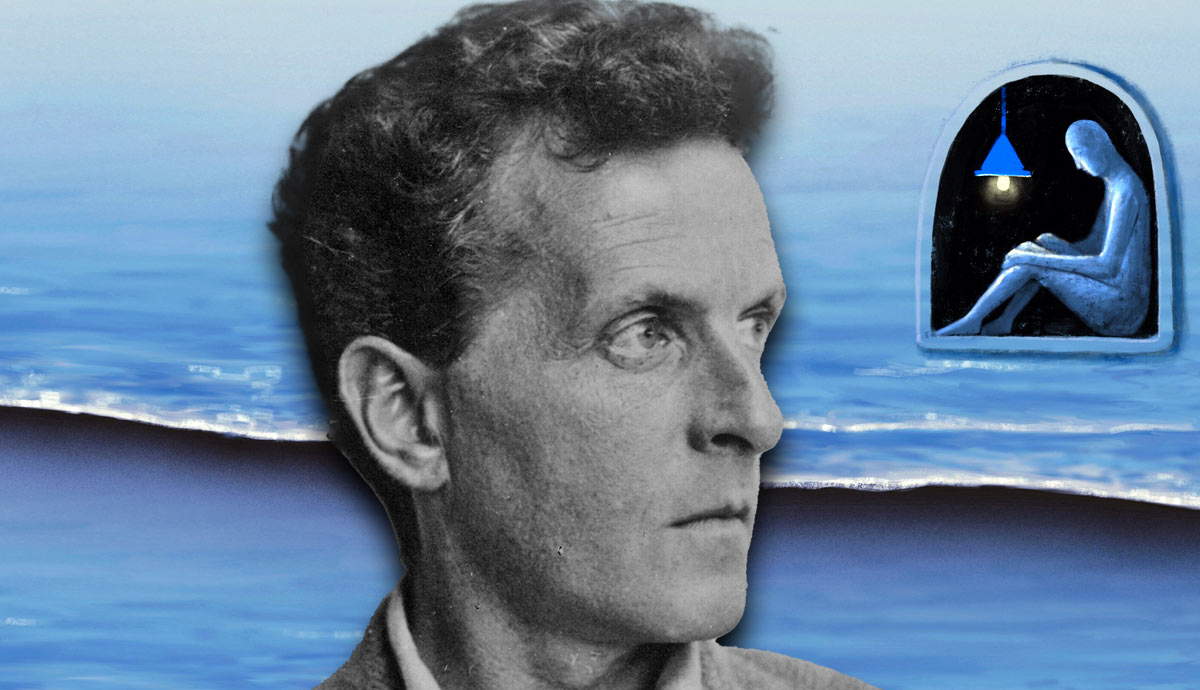

The Austrian-British philosopher Ludwig Joseph Johann Wittgenstein (1889-1951) is rightfully considered one of the most original and outstanding thinkers of the 20th century. His legacy in the fields of philosophy of language, logic, and mathematics, as well as the philosophy of mind, had a huge impact on all subsequent European philosophy and science in general. Moreover, it is safe to say that Ludwig Wittgenstein occupied a special place in the history of science.

The Philosophical Investigations is one of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s most important books. It was first published in 1953 and has been causing headaches (in the best way) ever since with its complex ideas about language and meaning.

At its core, Philosophical Investigations is essentially a giant puzzle asking you to question everything you think you know about language and communication. Wittgenstein takes everyday words and phrases that seem simple and straightforward—like “I love ice cream” or “The sky is blue”—and makes you take a closer look at what they really mean.

Using metaphors aplenty, Wittgenstein turns the English language on its head. He asks us to consider things like context, customs, and even individual perspectives when it comes to decoding what someone’s actually trying to say.

For example: imagine you’re at a crowded party, and someone says, “Hey! Pass me my drink!” How do you know which drink they’re referring to? Do they have multiple drinks? Is there only one drink within reach? Or maybe they’re just joking around?

This kind of “confusion” about everyday language represents the starting point of some of Wittgenstein’s most fascinating ideas. His theories about the fluidity and ambiguity of language have enormously impacted modern philosophy (not to mention linguistics, cognitive science, and psychology).

Language Games as The Key Concept of the Philosophical Investigations

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations is a giant puzzle, pushing us to delve deeper into the words we use and contemplate their meaning in various contexts. One of the key concepts he came up with is that of a language game. So what is a language game? In short, it means understanding how our speech functions within different settings or life forms.

As per Wittgenstein’s idea, the manner by which we utilize language depends on our experiences and activities; hence, if one wishes to comprehend its purpose, one must first understand where it takes place.

For example, imagine playing a game of soccer. There are certain rules and expectations for using your body and interacting with others on the field. The same goes for language: there are rules for grammar and vocabulary that we need to follow for our utterances to make sense to others around us.

But even more than just rules, Wittgenstein saw language games as key to understanding how we communicate ideas, both between individuals and across cultures. Every situation or life-form has its own distinct set of assumptions about what certain words mean or how they should be used—kind of like having your own secret code!

This idea leads to some pretty wild philosophical questions about whether it’s even possible to truly understand someone else’s perspective or ideas (think: “Can I really know what you mean when you say ‘love’ if I’ve never experienced it myself?”). It also challenges us to see communication not just as transmitting information from one person to another but as shaping our sense of reality.

All in all, Wittgenstein views language games as an essential feature of human existence—something that not only allows us to communicate with each other but also connects deeply with our individual experience of living.

Meaning as Use

One of the main ideas that Wittgenstein discusses in Philosophical Investigations is that of “meaning as use.”

Wittgenstein argues that the meaning of a word isn’t some kind of separate “thing” that exists all on its own. Instead, it’s something that arises from how we use it in language. Think about it like this: words are like puzzle pieces. They only have meaning when they’re connected to other pieces around them.

Using metaphors to help us unpack this idea: imagine you’re trying to complete a jigsaw puzzle. Each piece may look completely different but put it next to the right piece, and suddenly, all those weird shapes start to make sense!

Now apply this same logic to language. The meaning of a word can only be understood when you consider how it fits into specific “language games” (which Wittgenstein describes as specific ways we use language in different contexts).

So, for example, if I say, “I’m going green,” without context, you might scratch your head and wonder if I’m talking about my diet, painting my face, or about my vehicle choice…but in the context of an environmental activist group meeting, you’d quickly realize I mean I’m becoming more eco-conscious!

This theory of meaning also challenges traditional ideas like Platonism, which suggests that there is some sort of universal definition or essence behind every word—according to Wittgenstein, each word only has significance within our human context and the way we live our lives.

It’s worth noting that this concept of meaning as use has been applied not just in linguistics but also fields ranging from psychology to anthropology—which speaks not just to Wittgenstein’s genius but also his enduring influence.

Rules and Rule-Following As the Basis of Language

Wittgenstein’s concept of rules and rule-following is an essential part of his work. In Philosophical Investigations, he provides a basic example of following a rule by continuing a sequence of numbers. If a teacher shows a student this sequence: 2, 4, 6, 8… and asks them to continue it, the rule they want the student to grasp is that of adding 2.

But what does it really mean to follow a rule? Is it merely about replicating the figures in their proper order, or could there be something more significant beneath this surface explanation?

This thought-provoking question invites us into Wittgenstein’s complex exploration of language and its associated concepts—one which continues today as we strive for greater understanding within our world.

According to Wittgenstein, the key to unlocking our understanding of rules lies in recognizing their connection with a larger societal framework. Rules are not merely arbitrary commands we have no choice but to obey; rather, they form part of an encompassing “form of life” that determines how we think and behave.

Take games, for example. When we play games, we’re following all sorts of implicit rules about how the game is supposed to be played—from Monopoly to chess to hide-and-seek.

But those rules aren’t fixed or unchanging; they can morph and shift over time as we renegotiate what counts as fair play or good sportsmanship.

This flexibility is both liberating and intimidating. On the one hand, it means that there’s no one-size-fits-all definition of what constitutes rule-following—instead, it’s always contingent on context and situation.

On the other hand, it also means that we have immense power to shape our own identities and actions based on how we interpret these rules.

Ultimately, Wittgenstein suggests that understanding language (and, by extension, all forms of communication) requires us to grasp this fluidity and context-dependence of rule-following.

We can’t simply rely on rigid definitions or strict guidelines—instead, we need to be able to read between the lines and recognize when words or actions shift from one context to another.

Wittgenstein’s Private Language Argument

Another important contribution of Wittgenstein to the philosophy of language is his private language argument. In a nutshell, Wittgenstein was convinced that the idea of a purely private language—one that only one individual can access—is fundamentally flawed.

He believed this because, according to him, language and meaning are social constructs built from shared practices and conventions among different people. There is no language without shared practices.

As always in the philosophy of language, it all boils down to the notion of what we mean by “meaning.” According to Wittgenstein, words only have meaning when they’re attached to an agreed-upon common use—a kind of shorthand for communicating ideas to other people.

For example, if someone says, “I’m going to grab a coffee,” they expect that whoever hears them is going to understand what they mean by “coffee”—simply because there are well-established conventions around what it refers to.

Now, imagine constructing a language in which words only belong to a single person’s consciousness, without it being possible to share their meaning with anyone. It sounds like it might work, but on closer inspection, it’s not really feasible as such communication would be impossible since words lack any fixed, stable reference point. Without rules, there would be no meaning; and rules can be fixed only by a shared practice.

That’s where the private language argument comes in. If language is truly private—if someone could invent words with secret meanings they never communicate with others—how could anyone else make sense of what they’re saying?

Without common conventions and established practices surrounding specific phrases or words known as “public criteria,” it would be virtually impossible for anyone else (even highly empathetic individuals)to know which queries are being referred to or addressed. However, Wittgenstein goes even further: not even the person using the private language could make sense of his own sentences!

At times philosophers like Descartes had claimed the possibility of having privileged access to their own thoughts, but as per Wittgenstein or his line of thought, this privilege is void because ideas are an outcome of social operations arising from primary triggers provided by our senses.

So at its very core, the private language argument shows us that we can’t escape the fundamental fact that language relies on shared understanding and consensus. Without a basic framework of social norms or common use to define what words mean, language simply cannot exist.

So, What Is Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations Significance in the Philosophy of Language?

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations has undeniably had a huge impact on the philosophy of language, and with good cause. This extraordinary exploration into linguistic expression encourages us to challenge our existing understandings of communication and meaning.

At its heart lies an in-depth analysis of how ambiguity and fluidity are inherently embedded within language; Wittgenstein suggests that we can’t see it as something which follows precise rules or definitions because meanings are often shaped by experiences set against a larger social context.

Instead, Wittgenstein urges us to consider how we use words in practice—how their meanings shift depending on their spoken context. He emphasizes that language is inherently creative and adaptive and not just limited to set definitions or rigid categories.

As we saw, a key idea in Philosophical Investigations is Wittgenstein’s notion of language games. When we communicate with one another, it’s almost like we’re playing a game with certain rules—but these rules aren’t set in stone. They constantly evolve and adapt as we engage in conversation, working together to create meaning through shared practices.

The ideas in Philosophical Investigations inspired scholars to challenge previously existing dogmas about communication and meaning. What makes this work so significant is Wittgenstein’s groundbreaking challenges to our beliefs concerning language; he forces us to look more closely at how complex yet creative it can be when we try conveying a message or expressing ourselves through words. Wittgenstein is reminding us that words aren’t simply symbols on paper or a screen but rather powerful instruments for understanding the world around us.