Master of the impossible, M.C. Escher’s illusionary, labyrinthine worlds have fascinated artists, designers, mathematicians and geologists alike. His meticulously rendered, illogical black and white drawings and prints seem born from the subconscious.

Escher’s dream-like realms of Surrealism, but he was an isolated figure with a singular vision, who found international fame in his later years and remains, to this day, one of a kind.

Early Years in the Netherlands

Born Maurits Cornelis Escher in 1898, Escher was one of five children raised in a well-off family household in the Netherlands. His family moved to Arnheim in 1903, where Escher began school, although he was deeply unhappy and even described the experience as “hell.”

As an adolescent he discovered a passion for art which gave him a sense of direction and purpose, and in 1917 began working with his friend Bas Kist to produce a series of prints in the Dutch artist Gert Stegeman’s studio.

Learning the Graphic Arts

Escher initially began training to become an architect at the Haarlem School for Architecture and Decorative Arts, but a teacher persuaded him to shift to the graphic arts instead, where he learned to create lithographs and woodblock prints. Even so, architectural forms and designs continued to feed into his visual language for the rest of his career.

A family trip to Italy in 1921 also ignited a close affinity with the landscape, where he created detailed studies of trees and landscapes which he would translate into print designs. A year later he travelled around Spain, visiting Madrid, Toledo and Granada, mesmerised by the Islamic repeat patterns in the Moorish 14th century Alhambra.

The Influences of Italy and Spain

Escher returning to Italy in 1923, holding his first solo exhibition in Siena, exhibiting a series of prints which revealed exquisite skill and craftsmanship, alongside a preoccupation with repeat pattern. Influences came from the finely detailed drawings of Leonardo da Vinci and the carefully rendered prints of Albrecht Durer.

RELATED ARTICLE:

Edvard Munch: A Tortured Soul

In Siena, Escher met and fell in love with Jetta Umiker, a Swiss holidaymaker, and the pair married and settled in Rome a year later, going on to have three sons. By 1929, Escher had established a wider reputation as a commercial artist, holding popular exhibitions in Holland and Switzerland. But in the mid-1930s Escher and his family fled Italy following the rise of Fascism, relocating to a new home in Switzerland.

The move prompted a new phase in Escher’s art as he revisited the Alhambra with a greater determination, gathering material which would play out in his art as mathematical designs and geometric patterns, but with representational forms embedded into them. These later became known as his ‘transformation prints,’ including Day and Night, 1935 and Reptiles, 1943.

Before and During the War

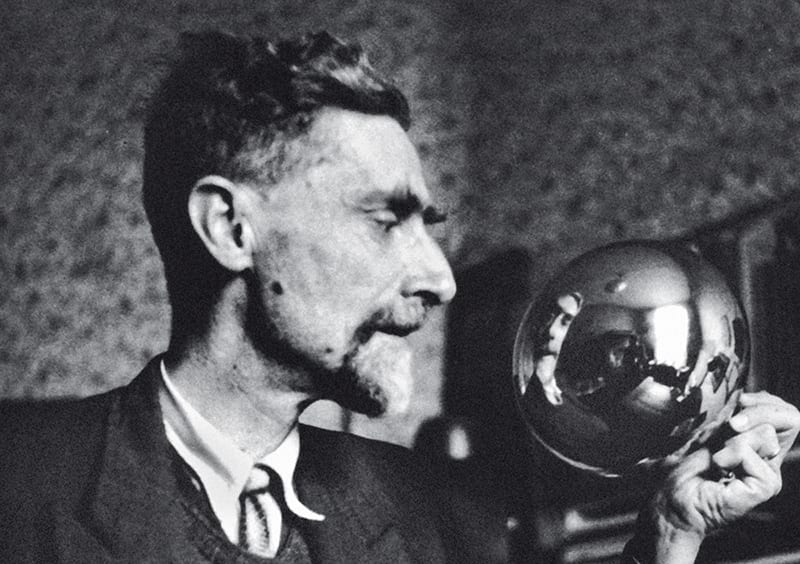

The Escher family spent a brief period in Uccle in Brussels, where Escher began his ‘impossible reality series’, where two separate realms merge into one, including Still Life and Street, 1937. Self-portraits were also are recurring themes, as seen in his iconic lithograph Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935. Following the outbreak of war, they sought refuge in Escher’s home country, settling in the Baarn area of the Netherlands.

Escher’s art shifted away from tessellated patterns towards the realms of art and illusion during this time, such as Encounter, 1944 and Drawing Hands, 1948, which explore the boundaries between the two dimensional picture plane and its ability to convey form and space. “It is … a pleasure … to mix up two and three dimensionalities,” he wrote, “flat and spatial, and to make fun of gravity.”

Finding Fame

By the 1950s Escher was making his most well-known artworks, including architectural conundrums like Relativity, 1953, while the commercial appeal of his art earned him international fame throughout Europe and the United States. Demand for his prints was so high that he kept increasing his prices to put off buyers, but it made no difference.

This populist and easily reproducible strand of his art, as well as his slick, graphic style led him to be taken less seriously by the art establishment during his lifetime and historically he was rarely featured in published art anthologies. However, since the turn of the 21st century attitudes have been gradually shifting in his favour as various institutions across Europe and the United States have organised major retrospectives celebrating his art and its legacy. His work also had a lasting influence on Op Art, which took his mind-bending visual effects into new realms.

Later Years

After a landmark exhibition in Amsterdam Escher’s prints caught the attention of mathematicians Roger Penrose and HSM Coxeter, who saw parallels between the repetition and order of his work and their practice, and Escher would develop mutually beneficial working relationships with both.

RELATED ARTICLE:

5 Techniques of Printmaking as Fine Art

Other non-art world circles developed an affinity for Escher’s art, including California’s psychedelic hippies, who were attracted to his mind-bending Surrealism, prompting Rolling Stone magazine to coin him as “the godfather of psychedelic art.” A private and introspective man, Escher was bemused but sceptical of his rising celebrity status, famously refusing to design an album cover for The Rolling Stones and turning down an offer to work with Stanley Kubrick.

In his later years, Escher focussed on mathematical shapes and designs with increasingly complex motifs, including Knot, 1966 and Snakes, 1969. As the last major artwork he ever made before his death in 1972, aged 73, Snakes was made from a complex set of nine separate, interlocking woodblock plates and introduced elements of colour, revealing his enduring and endlessly creative spirit of invention.

Auction Prices

The majority of Escher’s artworks were prints, which could be reproduced in multiples, making their market value lower than original paintings and drawings. Those that exist in smaller editions tend to sell for higher prices, while the ones he made many versions of are a much more affordable option for art buyers. Let’s take a look at some of his most expensive artworks:

This editioned lithograph print was sold at Swann Auction Galleries, New York, in 2008 for $28,800.

A version of this print was sold at Bonham’s, London, in 2018 with a final bid of $37,500.

A popular image in Escher’s collection, in 2017 one of these editioned Escher prints sold at Christie’s, London in 2013 for $57,000.

One of his most iconic works, this print was sold at Bonham’s, London, on May 22 2018 for $92,500.

This print sold at Sotheby’s, London, in 2008 for a staggering $246,000, while another version sold for $187,500 at the same auction house in 2019, revealing a high demand in his art.

Did you know?

While growing up, Escher’s family gave him the affectionate nickname ‘Mauk’, as an abbreviation of his full, first name Maurits.

At school Escher Found maths challenging, and it was only as an adult that he rediscovered the subject, particularly after reading a paper by George Pólya on “plane symmetry groups,” or repeat patterns on two-dimensional surfaces.

Escher was an intensely private man who would shut himself away while working. One of his three sons remembered back, “He demanded complete quiet and privacy. The studio door was closed to all visitors, including his family, and locked at night. If he had to leave the room, he covered his sketches.”

Although there is an effortless naturalism to Escher’s art, he often spoke about the months of anguish making just one work could cause him, and it pained him that nobody would really know how difficult his art was to make.

RELATED ARTICLE:

What Gives Prints their value?

It took Escher more than 30 years to earn enough money to support himself, but his wealthy family subsidised his lifestyle until then.

Escher and the mathematician Roger Penrose inspired each other’s practices; The Penrose Triangle was influenced by Escher’s art, while in turn Escher’s works Ascending and Descending and Waterfall sprang from Penrose’s ideas about order and pattern.

Throughout his long life Escher was hugely prolific, producing over 2000 drawings and 448 lithographs, woodcuts, and wood engravings.

Escher worked almost entirely in black and white, only introducing small areas of colour towards the end of his career.

The Escher in Het Palais Museum in The Hague was established in memory of Escher’s life’s work, although it was discovered in 2015 that the majority of the 150 works previously on display were in fact replicas rather than original prints.

The Gemeentenmuseum Den Haag in The Hague holds a large collection of original Escher prints which it often loans out to other museums and galleries.