Queens have long been both scrutinized and worshipped for what they wear. From the skirts of Isabeau of Bavaria, that were so voluminous that doorways had to be widened to accommodate them, to Kate Middleton’s on-point love of high street fashion, commoners have long been fascinated with royal trends. Yet, no other queen inspired a style revolution as much as Marie Antoinette. From her over-the-top pastel gowns adorned with ribbons and bows to her plain muslin dresses that attracted both admiration and scorn, the trends that Marie Antoinette set are still emulated by top fashion designers today.

Marie Antoinette’s Transformation From Archduchess to Dauphine

When Marie Antoinette first arrived in France to take her place as the dauphine, the year was 1770 and she was just 14 years of age. Austria had paid 400,000 livres for her trousseau, and the items within had been made in Paris. This was essential so that the young princess could look the part when presented to the sharp-eyed courtiers at Versailles.

On the day of her arrival in her new homeland, Marie Antoinette was dressed in a splendid Austrian wedding dress. Yet, as a symbolic act of shedding her Austrian ways in favor of embracing all things French, the young princess was made to remove this fine gown. Marie Antoinette was stripped down to her underwear, and re-dressed in French fashion, a change which was described as making her “a thousand times more charming”. The transformation had begun.

Rose Bertin: Marie Antoinette’s “Minister of Fashion”

Like many famous style icons, Marie Antoinette made use of the services of a stylist. Her chosen “Minister of Fashion” was Rose Bertin (1747-1813). Marie Jeanne “Rose” Bertin was a commoner, whom Marie Antoinette had raised up to be her number one fashion stylist and dressmaker at the court of Versailles. Naturally, Bertin also attracted other wealthy clientele from the queen’s inner circle, which made her a wealthy woman in her own right. Some of her clients included Marie Antoinette’s closest friend, the Princesse de Lamballe, as well as the portrait artist Vigee Le Brun.

Bertin was given free rein to create over-the-top formal dresses for her queen, suitable for formal appearances at court. Marie Antoinette was rumored to have had 300 dresses made for her each year, and she never wore anything twice.

Many of these dresses would have been the formal robe à la Française, which were already in fashion by the time the young Austrian Archduchess arrived at Versailles. The robe à la Française was defined by its open underskirt, wide panniers, and its use of heavy fabric with floral detail.

Bertin was also credited with making puce fashionable (puce is a dark color combination of brown, red, and purple — similar to the color of a flea). When King Louis XVI saw his queen wearing Bertin’s puce-colored creation for the first time, he exclaimed “that is puce!”. Despite this rather grotesque association with the much-loathed insect, puce took off in popularity because it was not easy to soil. The bourgeoisie were so taken with the color that cloth dyers could barely keep up with demand.

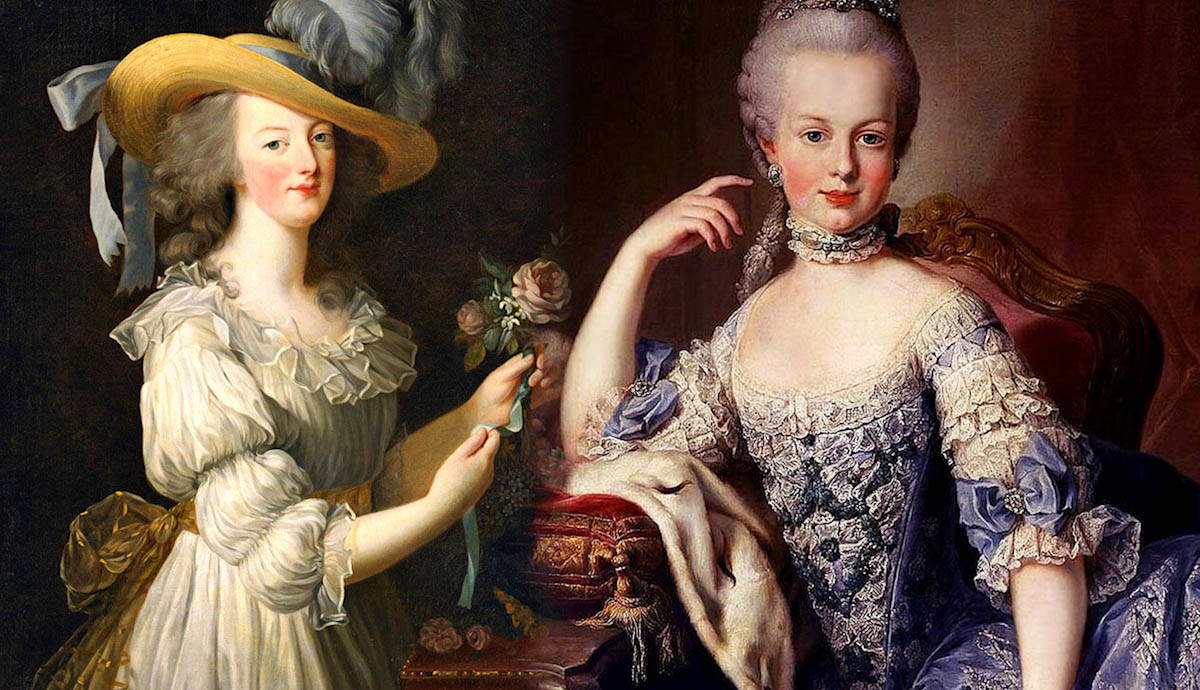

But it was Rose Bertin’s more casual creations made of muslin that the queen favored when she spent time at the Petit Trianon that caused an uproar. In an exquisite royal portrait of the French queen, painted by Vigee Le Brun (who was also a client of Rose Bertin), Marie Antoinette is depicted wearing a simple, unstructured dress made of white muslin, tied at the waist with a ribbon sash. Her hair is also styled in an informal fashion, loosely curled and adorned with a beribboned straw hat. This dress, the chemise á la reine, (or, robe en gaulle), was created for Marie Antoinette by Rose Bertin in 1781.

The Chemise à la Reine: Fashion Hit or Political Faux Pas?

To the modern onlooker, this portrait seems innocuous; to 18th century, pre-revolutionary France, it was an insult. The queen was lambasted for promoting fashion that used imported fabric rather than French silk, which had a negative impact on an already flailing economy.

Similarly, Marie Antoinette was criticized for dressing like a milkmaid. At the Petit Trianon, Marie Antoinette preferred to dress down, as an antidote to the rigidity of both the corseted clothing and the customs of the court. Dressed in her simple muslin outfits, Marie Antoinette could relax both literally and metaphorically.

When Vigee Le Brun’s portrait of the casual queen was shown to the public, they were offended and outraged that she could pretend to be a commoner for fun while thousands of her people were starving due to food shortages. Marie Antoinette’s contemporaries felt that, as queen, she should have been portrayed in a regal manner that befitted her station in life.

Nevertheless, this chemise-style gown took off not only in France, but in England too. This “underwear as outerwear” style revolution, though considered by some to be indecent, was adopted by Marie Antoinette’s contemporaries.

The chemise á la reine was embraced by wealthy women not only in France, but also across the rest of Europe and in England. Notable women who have been depicted in art as followers of this style of dress include Marie-Anne Paulze Lavoisier (1758-1836), wife and laboratory partner of French chemist and nobleman Antoine Lavoisier, Jane Buller, Lady Lemon (1747-1823), wife of an English lord and Member of Parliament, and Empress Elisabeth Alexeievna of Russia (1779-1826). The chemise à la reine is considered to be the precursor of the white flowing gowns of the Regency era (1818-1820), which were also loose, unstructured, and somewhat revealing.

By the time that Marie Antoinette reached her thirtieth birthday, she took a more sober approach to women’s fashion, which can be seen in the portraits made of her in those years. The Queen of France instructed her “Minister of Fashion” to create more serious outfits for her to wear. Marie Antoinette decided to stop wearing flowers in her hair, preferring headdresses made of velvet in darker shades of red and blue.

However, Marie Antoinette’s love of fashion never did truly wane. Rose Bertin continued to bring the queen gowns from her boutique in Paris even after she was placed under house arrest. It was one of these gowns that the maven of French fashion wore on the day she was taken from the palace and imprisoned at the Conciergerie.

Marie Antoinette’s Influence on Fashion Today

Contemporary fashion designers still consistently draw inspiration from Marie Antoinette’s iconic look, so far-reaching is the influence of Rose Bertin’s creations. Christian Dior, Vivienne Westwood, Christian Lacroix, and Thierry Mugler are all couturiers who have given a nod to the maven of French fashion in their whimsical designs.

Dior’s use of full skirts, fitted bodices, soft pastels, and intricate floral embroidery are all reminiscent of Marie Antoinette’s signature style. Vivienne Westwood has created frothy confections that embody the French queen’s taste for bow, ruffles, and lace. And for the high street shopper, the easy, breezy milkmaid look enjoyed a resurgence in the summer of 2019.

Marie Antoinette’s Fashion Legacy

Marie Antoinette’s style is immediately recognizable today. But, why has this one woman had such a long-lasting impact on the fashion world, a legacy other queens have failed to live up to? Perhaps it is because she was the ultimate “girly girl”. She indulged her love of pretty girly things to the fullest, particularly in the years before she had her children. Her style speaks to the little girl in all of us, the girl who can never own enough ribbons, and to whom everything should be pink.

One could hardly blame Marie Antoinette for her excessive love of couture. She was just a teenager when she came to France, and her marriage was barren for eight years. It was only natural that Marie Antoinette would throw herself into something like clothing in order to keep her mind off the fact that she was failing to do the one thing that she was supposed to do — which was to produce the next King of France. Her education, according to her biographer Antonia Fraser, was also woefully inadequate for a Queen of France. Therefore it is of little surprise that she had to find ways to entertain herself that did not involve politics.

If put into her pastel silk shoes, many of us would have done the same. It does her memory a wonderful service that today she is fondly remembered as more than a hapless victim of the French Revolution, but rather as one of history’s most-revered fashion mavens.