During the Middle Ages, numerous medieval women and men willingly chose to be walled up alive, something that seems unimaginable today but was ordinary at the time. Read on to discover why the Anchorites chose to be immured alive of their own free will.

Anchorites: The Earliest Form Of Monasticism

Anchoritic life dates back to the early Christian East. Anchorites and anchoresses were men or women who chose to withdraw from the secular world to live an ascetic life, dedicated to prayer and the Eucharist. They lived as hermits, and vowed to stay in one place, often living in a cell attached to a church.

The word “anchorite” comes from the ancient Greek ἀναχωρητής, a derivative from ἀναχωρεῖν, meaning “to withdraw.” The Anchorite way of life is one of the earliest forms of monasticism in the Christian tradition. The first experiences reported come from Christian communities in ancient Egypt. Around 300 CE, a few individuals left their lives, villages, and families to live as hermits in the desert. Anthony the Great was the most famous representative of the “Desert Fathers;” the early Christian communities in the Middle-East. He significantly contributed to spreading monasticism in both the Near East and Western Europe.

Just as Christ asked his disciples to leave everything behind to follow him, the anchorites did the same to devote their lives to prayer. Christianity encouraged them to follow the Sacred Scriptures. Asceticism (frugal lifestyle), poverty, and chastity were highly regarded. As this lifestyle attracted increasing numbers of worshippers, Anchoritic communities were created, and they built cells which gave isolation to their occupants.

This early form of Eastern Christian monasticism spread to the Western World during the second half of the 4th century. Western monasticism peaked during the Middle Ages. Countless monasteries and abbeys were built in cities and more in secluded locations. The Middle Ages also saw the birth of several religious orders, such as the Benedictine Order, the Carthusians, and the Cistercians. These orders tried to include hermits into their communities, absorbing them in a form of cenobitic monasticism. From then on, few individuals continued to practice their faith living as hermits instead of joining a religious community.

The Highest Form Of Monasticism

In Benedict of Nursia’s Rule of Saint Benedict (516 CE), anchoritic life stood for the highest form of monasticism. More experienced monks could attempt the risks of hermit life, fighting the devil and resisting temptation.

Anchoritic life boomed during the 11th and 12th centuries. Following the example of the saints, thousands of medieval women and men joined the flow and opted for this arduous lifestyle. They left everything behind and started preaching penance and the imitation of the apostles. Manual labor, poverty, and prayer were the fundamental pillars of their life. The historical context impacted this trend. It was a time of population growth and global changes in society; cities expanded, and a new division of powers was created. During this overturning of society, many people were left behind, too poor to fit in. Anchoritic life attracted many of these lost souls.

The Church was not against anchorites, but they knew they had to be supervised. Hermits were more inclined to excesses and heresy than monks living in communities. Therefore, along with the establishment of religious communities, the Church encouraged the sedentarization of anchorites, by creating single cells where individuals were confined. In this way, medieval women and men were looked after instead of abandoned to a hermit life in the woods or on the roads.

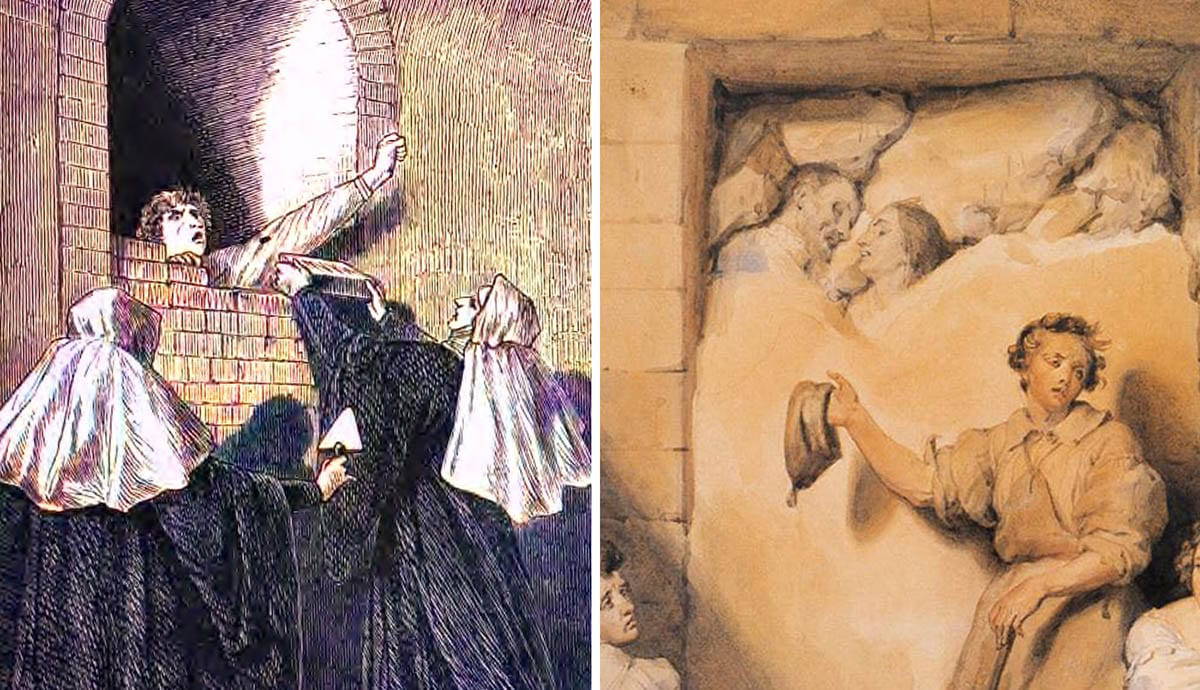

Women And Men Walled Up Alive In Small Cells

Anchorites and, more frequently, anchoresses, opted for this lifestyle, and some were not only locked up in a monastery — they were walled up alive. The act of walling up the anchorite symbolized his death to the world. Texts described anchorites as belonging to the “Order of the Dead.” Their commitment was irreversible. The only way forward was towards Heaven.

Yet, anchorites were not left in their cells to die. They could still communicate with the outside world via a small opening in the wall with bars and curtains. Anchorites needed clergy members and devotees’ assistance to bring them food and remedies and remove their waste. They entirely depended on public charity. If the population forgot about them, they died.

As sacred places, rules regulated the building of anchorite cells. A 12th century text reports that the cell or anchorhold was about 8 square feet. Along with the opening through which they received food and communicated with the outside world. Anchorholds contiguous to church walls also had a hagioscope or squint; a hole in the church wall for following services.

The interior layout was sparse. Several documents mention a pit dug in the ground. The anchorite stood in this pit when he was immured, and it became his grave upon his death. A table and stool and a few cult objects completed his possessions. Some anchorholds were larger, with two or three rooms on two floors, but most were small and poorly furnished. Hardcore anchorites lived in an unheated cell – but digs have shown that most had built-in chimneys.

An Integral Part Of Medieval Towns And Villages

Anchorites were part of ordinary life in Medieval Europe. They were integral members of society. Their sacrifice set an example; they reminded the local community of the importance of their actions in the mortal world.

Anchorholds were located at key points in a village or city. Many of them were built contiguous to church walls. Cells contiguous to churches, were often attached to the north-facing wall, the coldest part, next to the choir. In England, the anchorhold was usually inside the church, next to the private chapels.

Some could be found along cities’ defensive walls, usually near a gate. In that case, the anchorite served as the spiritual monitor of the town’s enemies. Even if they could not directly act in case of invasion, they sometimes were capable of miracles.

A 15th-century chronicle recounts the tale of the anchoress of Bavay, a town in northern France. She saved the local church from being burned down by “fierce captains” by begging them to stop in the name of Christ and offering to pray every day for their souls. Anchorholds could also be found on bridges, next to hospitals and leprosarium, or among cemetery graves.

Local authorities and monasteries cared for anchorites. Sometimes they were chosen after a moral investigation and became the property of the city or a monastery. The authorities paid for their food, clothes, medication, and funeral expenses. Even kings took anchorites under their protection. Charles V, King of France in the second half of the 14th century, requested the presence of the anchoress from La Rochelle. The King made her come to Paris and settled her in a nice cell because of her holy reputation. In England, records of royal accounts show that certain Kings provided pensions to several anchorites.

Who Chose To Be Locked In A Cell?

Who was devoted or mad enough to take this huge leap of faith? Today, choosing monastic life is a vocation. Most anchorites or anchoresses were laypersons, often poor and with no education. Exceptions also existed. Several wealthy men chose the anchoritic life. They spent their money in building their cells and even had a servant to look after them.

Most were medieval women. The wish to adopt an anchoritic life often came from a desire for repentance; several were former prostitutes. The Church used anchorholds as well as convents to keep them away from a life of lust. Some also became anchoresses because of their lack of prospects. Medieval women with no dowry were unable to get married or even join a religious community. Others were priests’ wives, who joined anchorite life after the 1139 Second Lateran Council imposed priest celibacy. Others were widows or abandoned wives.

Yvette of Huy, a Belgian girl from the end of the 12th century, became an anchoress for another reason. As a child, Yvette wanted to become a nun but her father, a wealthy tax collector, forced her to get married at thirteen. Yvette so ardently despised marital duty that she desired the death of her husband. Her wish was answered five years later when she became a widow. She refused to remarry and started caring for the poor and for lepers. Yvette spent almost all her fortune doing so, although her family tried reasoning with her by taking her children away. Instead, Yvette left everything to live in a cell among lepers. The saint became famous thanks to her devotion and the wise advice she gave. Devotees gathered around her cell and gave large donations, allowing her to supervise a hospital’s construction. Ultimately, she even succeeded in converting her father, who joined an abbey.

Anchorites: Saints And Madness

The anchorhold was clearly conceived to make its occupant suffer. The anchorite who became irrevocably dead to the world had to suffer, just as in the Passion of Jesus. The ideal anchorite overcame suffering and temptations, rising to holiness. His prison became the gateway to Heaven. But the reality was often far from that.

Certain anchorites carried on their sinful life, pretending to pray when passersby came near, or gossiping with them. As incredible as it may sound, being walled up alive became an enviable position. Anchorites were fed and cared for, while during these tough times, many people starved to death. Their sacrifice inspired respect and gratitude among their community.

Other anchorites who could not get used to this extreme way of life, experienced a dreadful fate. Texts report that some of them became mad and killed themselves, even though suicide was prohibited by the Church. A poem from the early 14th century tells the story of the anchoress of Rouen in north-west France. The text relates that she became mad, and she managed to escape her cell by the small window to throw herself in the burning oven of the next-door bakery.

In the 6th century, Gregory of Tours, the Bishop and famous historian, reported several anchorites tales in his History of the Franks. One of them, young Anatole, immured alive at the age of 12, lived in a cell so small that a man could scarcely stand up inside. After eight years, Anatole became mad and was brought to Saint Martin’s grave in Tours in the hope of a miracle.

Anchorites were an integral part of society throughout the Middle Ages, but they started disappearing at the end of the 15th century, during the Renaissance. Troubled times and wars undoubtedly contributed to the destruction of several cells. The Church had always seen anchoritic life as something potentially dangerous; temptations and heretical abuses were risky. Still, these were probably not the only reasons for their progressive disappearance. At the end of the 15th century, reclusion became a form of punishment; the inquisition locked up heretics for life. One of the Holy Innocents Cemetery in Paris’ last anchoresses was locked in a cell because she killed her husband.

Plenty of tales and legends recount the stories of medieval women and men who chose to spend the rest of their life walled up in small cells for their faith. As strange as it may look, anchorites were indeed an integral part of medieval society.