In the Platonic dialogues, Socrates gives us the impression that every act of knowing, more often than not, is accompanied by perplexity. Knowledge claims that we take for granted are often much more complex than they seem once we put them under philosophical investigation. What is more perplexing, is when knowledge becomes its own object in the field of epistemology. Our assumptions about how we know something, to what extent we know, and the validity of our knowledge, can determine any philosophical inquiry we pursue. Empiricism and rationalism have generally been the dominant epistemologies in Western philosophy, but what about knowledge that is beyond reason and sense perception? Is such knowledge within our capacity? And if so, how is it possible? Answers to these questions begin to unravel once we dive into the uncharted waters of mystical epistemology.

Mystical Epistemology: The Mystical Approach to Knowledge

We seldom find a general consensus on anything in philosophy, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that there is no common agreement on a precise definition of mysticism. Mysticism is a very broad term that can be used to describe a variety of phenomena. What most of these phenomena have in common is that they feature personal encounters with a transcendent reality. Mysticism is essentially an experience of a reality that is beyond the boundaries of our material world, a reality often considered divine. Mystical experiences can be characterized by feelings of union with that reality, ecstasy, love, or contemplation, but what is more important is that all such experiences have the property of knowledge.

Mystical experience and knowledge can be seen as two sides of the same coin because it is impossible to divorce this knowledge from experience. What is peculiar to mystical knowledge is that it is non-discursive, non-conceptual, and experiential. Mystical knowledge is an internal experience of knowledge occurring in certain states of consciousness that are unmediated by mental processes or sense perception. It cannot be communicated because it cannot be expressed in language or concepts. In Sufism, experiential knowledge is called “taste” (thawq), which serves as an analogy, because one cannot communicate or explain the taste of an apple to someone who has never tasted one.

The possibility of mystical knowledge depends on the metaphysical positions we maintain. If for example, we believe that nothing transcends our material reality, then we are unlikely to believe that mystical knowledge is possible. The primary question is then whether there is a transcendent reality to experience in the first place or not. We will see that mystical epistemology can take one of two roots depending on our answer to this question. If we answer affirmatively, as mystical traditions do, our epistemology will be grounded in metaphysical principles that explain these possibilities and that justify the validity of mystical knowledge. On the other hand, if we answer negatively, then our epistemology will explain mystical knowledge on material grounds and dismiss its validity.

Below, we will explore the metaphysical roots of mystical epistemology in different traditions, and we will address the skepticism that envelops them.

Sufism: The Heart of Islam

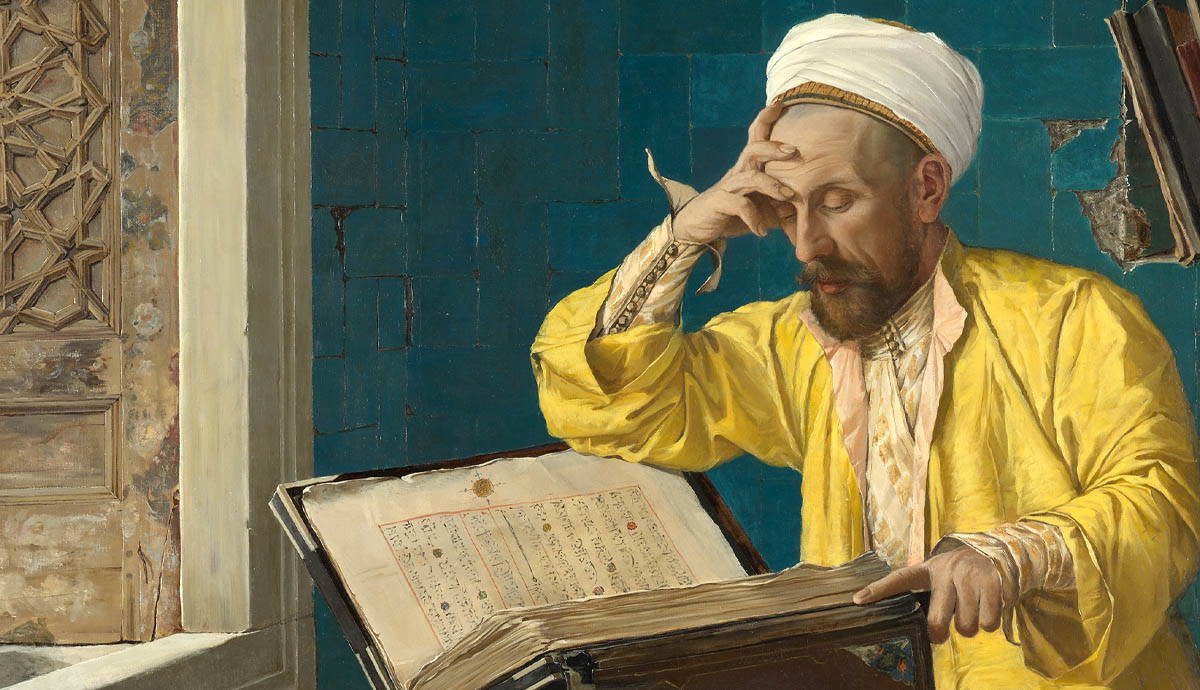

Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, has mystical epistemology at its center. Sufis believe that the purpose of creation is mystical knowledge, and they support their claim with the Hadith Qudsi in which God says: “I was a Hidden Treasure, and I loved to be known, so I created creation to know me”.

Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali, a key figure in Islam, deemed mystical knowledge as the apex of all knowledge, to which all other sciences are subordinate. Knowledge attained in this way is often termed in Sufi literature as “knowledge not of this world” (‘ilm la-duney), or knowledge that comes from within.

Mystical epistemology in Sufism is called the Science of Unveiling (‘ilm al-mukashafa). To understand what exactly Sufis mean by unveiling, let us explore two basic concepts from the tradition: the heart (al-qalb) and the Preserved Tablet (al-lawh al-mahfuz). Although related to the physical heart, the heart in Sufism is immaterial and immortal. It is often understood as the soul or spirit, although in Sufi anatomy, the heart is considered the gate between spirit (rawh) and soul or self (nafs). The heart is perceived as the locus of gnosis, the organ that receives inspired knowledge.

Ghazali, by way of analogy, viewed “the human heart and the Preserved Tablet as two immaterial mirrors facing one another” (Treiger, 2014). In Neoplatonic terms, the Preserved Tablet can be considered the Universal Soul. It is the blueprint of the world from time immemorial until the end of time according to which God creates the world. All possible knowledge and all forms of being are inscribed on the Preserved Tablet.

To go back to Ghazali’s analogy, the heart as a mirror has the potential to reflect the Preserved Tablet, attaining glimpses of its knowledge. This is why the heart in Sufism is otherwise termed “the inner-eye” (ayn-batineya) and is characterized by its vision (basira). However, there are veils that separate the heart from the Preserved Tablet, which is why the ultimate aim of Sufi praxis is the polishing of the mirror of the heart.

The human potential for knowledge is far from insignificant in Sufism. Ghazali insists that the knower “is someone who takes his knowledge from his Lord whenever he wishes, without memorization or study” (Ghazali, 1098). The knowledge humans can potentially attain within the Sufi epistemic framework is all-comprehensive. Taste (thawq) is fundamentally a gate to a level of prophecy that is open to non-prophets.

Jewish Mysticism

A central aspect of Jewish mysticism involves the concept of the ten sefirot. The sefirot (plural of sefirah) can be considered as the metaphysical structure of the divine emanations, or attributes, that result in the creation of our world. The ten sefirot expressed as the Tree of Life, include Chochma (wisdom), Bina (understanding), Daat (knowledge) Chessed (mercy), Gevurah (judgment), Tiferet (beauty), Netzach (victory), Hod (splendor), Yesod (foundation), and Malchut (kingdom). The sefirot are originally understood on the macrocosmic level as divine emanations, but there is another way to see them.

As in all Abrahamic religions, Judaism maintains that humans were created after the form of God. Among the implications of that belief in Jewish mysticism is that the sefirot can also be seen on the microcosmic level in human beings. Humans have within them all the ten sefirot, which are related to corresponding powers of the soul. What is of particular interest here are the powers of Chochma (wisdom) and Bina (understanding), as manifested in the human soul.

On the microcosmic level, Chochma can be seen as the source of inspired knowledge. As Rabbi Moshe Miller describes it, the Chochma of the soul represents “an intuitive flash of intellectual illumination which has not yet been processed or developed by the understanding power of Bina” (Miller, 2010). Unlike Sufism, in Jewish mysticism, particularly in the Chabad Hasidic school, the inner wisdom of the Chochma is associated with the mind, not as a conceptual and discursive understanding, but as a new insight or inspiration that is created ex nihilo.

On the other hand, Bina (understanding), is associated with the heart. Interestingly, it is the heart that understands the insights that the mind receives from Chochma and develops them into explainable concepts that are communicable.

Skeptical Interpretations of Mysticism

We could go on exploring mysticism by exploring bhavana-maya panna in Buddhism, Anubhavah in Hinduism, Christian Gnosticism, and much more, but let us now investigate the more skeptical approach to mystical epistemology. Why mystical knowledge attracts skeptics lies in the nature of the knowledge itself. After all, evaluating its validity is challenging, given that it is a non-conceptual private experience that cannot be universally reproduced. It then comes as no surprise that the word “mystical” is often synonymous with “hocus-pocus” in our modern Western culture. This is primarily the result of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, which dismissed the legitimacy of religious and occult disciplines.

As Alan Watts wittily remarked, “the world-conquering West of the nineteenth century needed a philosophy of life in which realpolitik — victory for the tough people who face the bleak facts — was the guiding principle” (Watts, 1966). What he is describing is an epistemological shift where empiricism and rationalism monopolized the foundation of justified knowledge, dismissing anything beyond their boundaries as wishful thinking.

Such ideas definitely influenced Steven T. Katz, one of the most renowned philosophers in the field of mystical epistemology. Katz developed a constructivist mystical epistemology. He argued that mystical experiences are shaped and even created by the specific socio-cultural and religious doctrinal training that a mystic receives throughout his or her spiritual path. His essential premise is that “there are no pure (i.e. unmediated) experiences” (Katz, 1978). This means that a person’s environment and religious training mediate and determine the contents of the individual’s mystical experience. The possibility and validity of mystical knowledge as defined above are therefore absent according to this theory.

There are several implications of Katz’s theory, namely that mystical experiences cannot be defined as sharing a common ground as essentialist theories would argue, but they must be viewed distinctively. Sufis will experience Tawhid, Buddhists will experience Nirvana, and each mystical experience must be seen as fundamentally different. This is plausible given that mystics interpret and describe their experiences according to their particular belief systems. But it is interesting to view this idea in light of the works of perennial philosophers such as Réne Guenon or Martin Lings, who not only argued that there is an essential commonality between mystical experiences in all religions, but that all religions share similar metaphysical principles.

The main postulate in perennialism could be termed as follows: “all religions are exoterically different, but esoterically the same”. Religions may vary in doctrines in the same way different languages differ from one culture to another, but they all serve as a means of communicating with the same Divine Reality. From a perennialist perspective, Katz’s theory cannot account for the essential similarity of diverse mystical experiences and fails to grasp the underlying metaphysical principles that unite the diverse exoteric expressions of religious doctrines.

Another implication of Katz’s constructivist mystical epistemology is that the knowledge gained through mystical experiences is a reproduction of the knowledge already acquired via religious training. The problem with this view is that it reduces a non-conceptual experience to a conceptual body of knowledge. Take for instance our example of tasting an apple. A person may have dedicated all the years of her life to studying taste pores and apples, but to what extent can this conceptual knowledge shape or produce the actual taste of an apple?

When analyzing mystical experience, it is important to recognize it as an experience. Conceptual and non-conceptual knowledge are qualitatively different. To assume that studying conceptual doctrines and even the discursive mystical literature of a given religion equates to studying the non-conceptual and non-discursive mystical experiences of its believers is erroneous.

Katz’s theory falls into the trap of what is called a post hoc fallacy, in so far as he does not have sufficient grounds to assume a causal relationship between conceptual doctrinal knowledge and mystical experience just because the former precedes the latter. Not only does this understanding rule out the possibility of an individual without religious training having mystical experiences, but it also cannot accommodate for the historical phenomenon of mystical heresy. Take Al-Hallaj for example, a famous Sufi who was imprisoned and executed due to the unorthodoxy of his ideas. Most mystics were historically attacked by their communities due to the unconventionality of their beliefs versus the more conservative doctrinal teachings that dominated the intellectual milieu of their communities. The insights that mystics gain from their experiences are often different and sometimes contradictory to existing religious doctrines.

Madness, Mysticism, and Philosophy in Epistemology

Remaining faithful to Katz’s skeptical spirit, we could say that the knowledge experienced through mysticism, if not a reproduction of previously learned concepts along the mystic’s path, is an outcome of fantasy or delusion. We could even argue that mystical experiences are the outcome of psychological imbalances and we could support ourselves with the numerous studies that compare mystical experiences to psychosis. Should we then consider mysticism as spiritual enlightenment or madness?

Unlike our common perception, madness and spiritual enlightenment were not always seen as a dichotomy. In fact, from an anthropological perspective, shamanic cultures still consider symptoms that are deemed pathological in modern psychology to be signs of spiritual emergence. Individuals who experience such symptoms are taken to be initiates in a process of spiritual training.

In the Platonic dialogues, Socrates reminds us that “the men of old who gave things their names saw no disgrace or reproach in madness” (Plato, 370 BCE). According to him, “the highest goods come to us in the manner of madness, inasmuch as it is bestowed on us as a divine gift and rightly frenzied and possessed” (Plato, 370 BCE). What is interesting here is that Socrates does not view madness as an illness. Quite the contrary, he considers madness a remedy to the “dire plagues and afflictions of the soul” (Plato, 370 BCE). Socrates is not denying there are psychological illnesses, but he does not categorize madness as one. What Socrates calls madness is otherwise known as theia mania — divine madness.

There are four kinds of divine madness outlined by Socrates. The one of interest for our exploration is associated with prophecy. In his book Divine Madness: Plato’s Case Against Secular Humanism, Joseph Pieper’s extensive analysis of Plato’s theia mania explains it as a “loss of rational sovereignty [in which] man gains a wealth, above all, of intuition, light, truth, and insight into reality, all of which would otherwise remain beyond his reach” (Pieper, 1989). In that sense, theia mania seems to be identical to mystical knowledge. Plato’s dialogues seem to invite us to redefine our derogative understanding of madness, and to consider it as even superior to sanity, the former being divine and the latter being human.

Plato, who coined the term philosophy (philosophia) in his famous dialogues, would have disagreed with the skeptic philosophers who dismiss the possibility and validity of mystical epistemology. In fact, in the Phaedo, we find Socrates saying that “mystics are, I believe, those who have been true philosophers… and I have striven in every way to make myself one of them” (Plato, 360 BCE). Indeed, the true lover (philo) of wisdom (sophia) in this sense, is better described as a mystic, who blurs the line we commonly draw between mysticism and philosophy.