Paper money (also banknote or bill) was first invented in China’s Song Dynasty (CE 960-1279) after a long process that can be traced back to the 3rd century BCE. Eventually, coin currency became too cumbersome and devalued, so various economists, philosophers, and emperors looked for answers. By the medieval era, the Chinese had developed new technologies, as well as different ways of visualizing money, which allowed them to develop the world’s first paper money. The following is an examination of the process that led to the emergence of paper money in medieval China.

Before Paper Money

The development of paper money was the result of a long process that began centuries earlier, thousands of miles away in the Near East. The Lydians were the first people to mint state supported coined currency in the 7th century BCE, and shortly after others followed. The Achaemenid Persians, Greeks, and Romans all developed coined currency from silver, gold, bronze, and copper, which provided the basis for the economies of medieval Europe and the Middle East. But as coined currency was being developed in the West, it was also flourishing independently in the East.

The Mauryan dynasty of India (c. 321-185 BCE), the Qin dynasty of China (221-206 BCE), and the Han dynasty of China (206 BCE-CE 220) were the earliest and most successful Asian states to utilize coined currency. These states disseminated the idea of coined currency throughout southern and eastern Asia, helping to prepare the continent for the eventual development of paper money. It was in late antiquity when the economic ideas of the West and East finally met along the Silk Road, which proved to be another major step in the development of money.

The Silk Road and Coined Currency

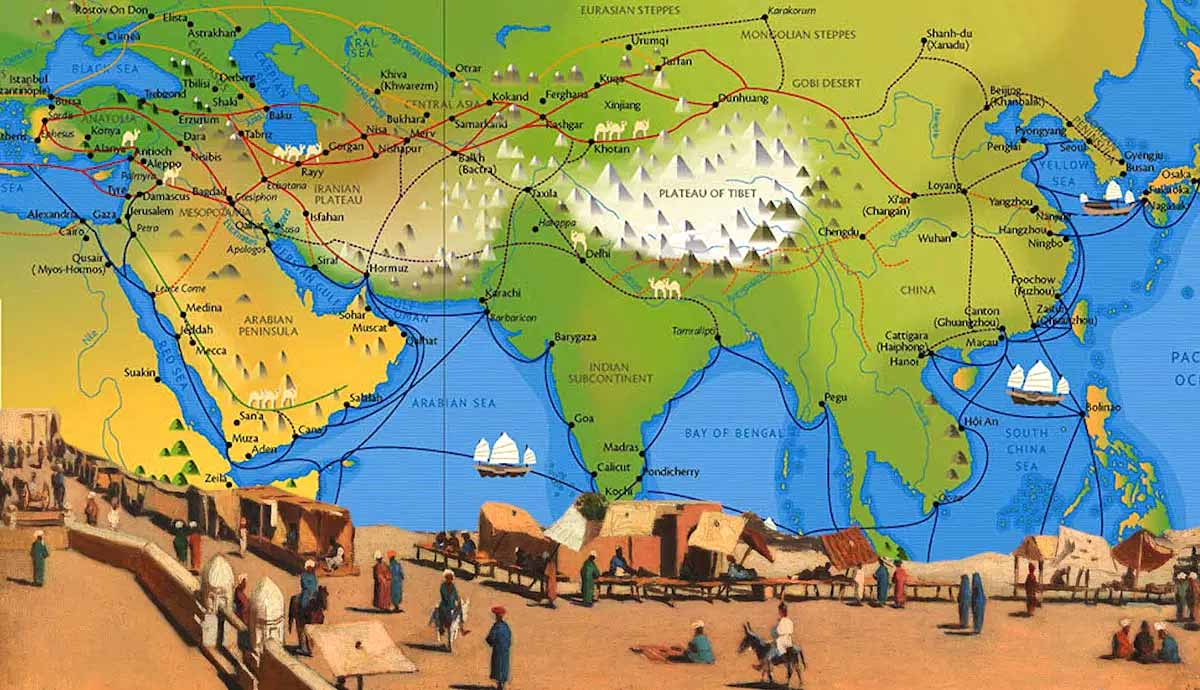

The Silk Road was actually a series of overland and sea routes that connected east Asia with the Middle East and Europe. The first Silk Road system existed from the late-2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE, which was responsible for moving goods, ideas, and people. The first Silk Road system included the states of Han China, Parthian Persia, Rome, and the Kushan Empire. Among those states, the Kushan Empire is often overlooked, but its leaders played an important role in the development of coin and paper currency.

All four of the major Silk Road states used copper, bronze, gold, and silver coins, but they used different systems of weights. A Roman, Kushan, Parthian, and Han silver coin may have looked similar, but because they often had different weights their inherent values were different. This situation could and did cause problems for long-distance merchants who wanted to trade coins of one empire for another. The Kushan rulers came up with a simple yet effective way to convert one trade or convert currencies by introducing a Kushan coin that was based on the Roman weight standard. Ideas such as this would percolate throughout the late ancient and early medieval worlds, ultimately leading to the creation of paper money and monetary standardization.

Chinese Coined Currency

As coined currency developed in China, it looked physically different than coinage in other locations. The Han and Qin authorities developed a method of standardization known as “strings” or guan. In this system, 1,000 bronze coins with square holes were threaded together to create one “string” or guan, making it the currency standard of ancient China. The guan standard was codified in the Tang dynasty (CE 618-907), but during that time the Chinese economy moved closer to paper money.

The first use of paper banknotes, known as “flying cash,” was in the early 800s between provinces. This was because, although the guan was the standard of the Tang government, different regional coins were still used. Originally, flying cash was just used by provincial officials, but it was also later permitted for merchant use. The evolution to paper money was well underway when the Song dynasty came to power, but other conditions still needed to be met.

The Transition to Paper Money in the Song

The Emperor Taizu (ruled CE 960-976) further standardized China’s coin currency across all regions by eliminating existing regional coins. The new, standardized coin became known as the Song yuan tongbao (primary circulating treasure of the Song), but it quickly encountered problems. By 1080 there were five million strings of the Song yuan tongbao in circulation, which itself was probably too much. Lead was added to the high number of bronze-coined currency circulating in the Song economy, which created crippling inflation. The otherwise prosperous and stable Song economy began to teeter, so forward-thinking leaders looked to paper for a solution.

In addition to the devaluation of the coined currency, a number of other factors, some practical and some philosophical, led to the use of paper money. First, the high demand for bronze, copper, and iron created a dearth of materials to make coins. Iron and copper were needed to make weapons and tools for the expanding Song Empire, and bronze is an alloy derived partially from copper. As the Chinese began using these commodities for things other than coinage, they began to view the concept of money differently. Song officials and philosophers began to see money not so much for the value of the token itself, but as a means of payment and exchange. Once this view was accepted, then the transition to paper currency was inevitable.

The transition to paper money would not have been possible without the proper technology. The invention of the movable type press, probably by Bi Shen in the 1040s, combined with the existing knowledge of paper making, made paper money a reality. Unfortunately, no samples of the earliest paper currency notes survive, although texts from the era describe how they were made and what they looked like. The notes were made through multiple impressions of three colors: red, black, and blue. The notes were marked by their value and decorated with narrative scenes and iconic emblems of the era.

One interesting element of early paper currency in China that may have been a component of both its success and failure was its decentralization. A number of different paper currencies were issued during the Song dynasty, with no single currency existing until the final decade of the dynasty. Instead, there were several “currency zones” throughout the empire, where regional officials would issue their own currencies that were authorized by the emperor. The earliest paper currency used was the jiaozi in Sichuan, which proved to be quite successful. In 1160, the paper currency known as the huizi was first issued by Goazong (ruled 1127-1162), the first emperor of the Southern Song dynasty. The huizi would become the most important and widespread of all paper currencies.

The huizi was far ahead of its time in many ways. The emperor issued each series of the note with fixed terms of expiration to fight inflation and lessen the effects of counterfeiting. Between 1168 and 1264 the Southern Song emperors issued eighteen series of the huizi. The Song central economy planners tied the huizi to the coined currency still active, with one huizi equaling one guan. Later, smaller paper denominations were printed that equaled partial strings of 200, 300, and 500 coins. The huizi was backed by silver, so the value of printed notes was theoretically not supposed to surpass the value of the silver supply. The Song leaders eventually printed more money than the value of the silver supply, devaluing the currency and creating inflation.

Early Paper Money Elsewhere

The primary rival of the early Song dynasty was the Jurchen Jin dynasty in northeastern China. The Jurchens eventually forced their way into Song territory, conquering northern China and vanquishing the Song dynasty to southern China. From 1127 to 1234 the Jurchens ruled northern China, following a policy of cultural and economic continuity from the Song. The Jurchens issued paper money notes beginning in the mid-1150s based on the Song notes originally issued in the Sichuan zone. The concept of paper money was then inherited when the Mongols conquered China and established the Yuan dynasty in 1271. As these advances in paper currency were taking place in the East, the West was lagging far behind, although some innovations were taking place there as well.

The legendary crusader military order, Knights Templar, were the first people to develop a proto-paper money in Europe. Churches throughout western Europe served as banks for the Templars, who serviced knights and other pilgrims who traveled to the Holy Land during the Crusades in the 13th century. The process worked in the following manner. A pilgrim would deposit his funds at a church or Templar castle in Europe, be given a paper note, and would then make the long journey. Once the pilgrim arrived in the Holy Land, he simply redeemed the note for coined currency, minus a small service charge. Although the Templars initially avoided charges of usury by not charging interest, they were still subjected to the Inquisition in 1312. The idea of paper money in Europe temporarily died with the Inquisition, but it was likely revived by the Silk Road when European merchants came into contact with Mongol paper money, later bringing the idea back to Europe. By the late High Middle Ages the idea of coined and paper currency had come full circle along the Silk Road.