The Spanish master Pablo Picasso is considered one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. His works have changed the course of art history forever. But how much of Picasso’s modernism was built on art coming from the African diaspora, and why is its indisputable influence on the artist’s work still not widely acknowledged? Read on to learn more about the relationship between African art and Picasso’s pieces.

African Art and Picasso

By the late 19th century and as a direct result of imperialism, thousands of African objects had arrived in Europe. Far from being considered artworks, they were considered artifacts of colonial conquests and held little to no economic value. But during the early 1900s with Picasso leading the way, African art aesthetics became a source of profound inspiration for the School of Paris, which had been searching for new and radical ways of representation. Picasso saw in African figuration a religious depth and ritual purpose that both startled and moved him. Its sophisticated use of flat planes and bold contouring was unlike anything the artist had encountered before.

But while the impact African art had on Picasso, and on the birth of Cubism as a whole, has been examined tirelessly, the works that inspired an entire movement are rarely examined in their own right. Instead, non-Western art is often viewed as the tool that enabled European artists such as Gauguin, Braque, and Picasso to bring forth a pictorial revolution, a tool that was quickly disregarded as soon as this was achieved. African artisans had been abstracting the human figure for centuries. So how much of what established Picasso as one of the founding fathers of modern art was borrowed from a continent he knew very little about?

African Art in Europe: Intrigue and Contempt

Until fairly recently, the Western art world’s adaptation of traditional African visual culture was referred to as Primitivism, a term which is now considered outdated due to its problematic connotations. At the turn of the 20th century, the European elite believed Africa and Oceania to be primitive lands rife with mysticism and savagery. At the same time, many appropriated these cultures for their own artistic and social gain, fascinated by an exotic fantasy of the non-Western. But very few had a sophisticated understanding of the cultures and mostly nameless African artists that they were borrowing from.

French colonies included French Sudan, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Dahomey, and Niger. Looted objects from these territories were brought over and poorly displayed in the notoriously dingy and run-down galleries of museums such as the Trocadero Museum of Ethnology, now the The Musée de l’Homme, in Paris and the British Museum in London. The ceremonial masks, sculptures and totemic carvings that were dispersed throughout Europe originated from several regions spread across an entire continent but came to be generalized as tribal art. They could be found at flea markets and in pawn shops, but little was known about their makers or the meaning behind their creation.

Europe was both fascinated and shocked by African objects, viewing their spirituality with a mixture of intrigue and contempt. It is important to note that unlike Western art, these objects had been created with function, rather than art in mind. While their function varied depending on region and religion, they played (and in many cases, continue to play) an important role in ceremonies and rituals celebrating religion, social status, and rite of passage.

Picasso’s African Art Encounter

In the spring of 1907, Henri Matisse was on his way to visit the American writer and collector Gertude Stein in her Paris home when he stopped in what used to be referred to as a ‘curio-shop’ to purchase a small African sculpture. Picasso, who was also visiting Stein when Matisse arrived, was immediately captivated by the sculpture that was later identified as a Vili figure from what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The artist, who was known to be extremely superstitious, believed in the magical and transformative power of objects. According to Max Jacob, French poet and lifelong friend of Picasso, the Spaniard clutched the small sculpture in his hands all night, inspired by its elongated features, streamlined forms and spiritual purpose.

The encounter ignited something profound in the twenty-five year old Picasso, who had recently come out of his Blue and Rose periods and was earnestly searching for a source of inspiration that would catapult him to the forefront of the avant-garde. A few days after discovering the Vili sculpture, the artist visited the Trocadero Museum with fellow artist and friend André Derain.

Picasso would later acknowledge this visit as a pivotal turning point in his artistic trajectory: “A smell of mold and neglect grabbed me by the throat. I was so depressed that I would have chosen to leave immediately,” Picasso said of the Trocadero. “But I forced myself to stay, to examine these masks, all those objects that people had created with a sacred and magical purpose, to serve as intermediaries between them and the unknown and hostile forces that surrounded them, thereby trying to overcome their fears, giving them color and shape. And then I understood what painting really meant. It is not an aesthetic process, it is a form of magic that stands between us and the hostile universe, a means of taking power, imposing a form on our terrors as well as our wishes. The day I understood that, I found my way.”

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon & Cubism

Any art historian will tell you that Picasso’s iconic 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was seminal for the development of Cubism. Soon after the artist visited the Trocadero, he revisited a composition he had been working on in his Montmartre studio. The work-in-progress portrayed nude sex workers in a brothel he frequented on Carrer d’Avinyó in Barcelona, Spain. The final oil painting, which stands nearly two and a half meters high and just over two meters wide, depicts five women with faceted, angular bodies who appear to be almost unaware of each other’s presence.

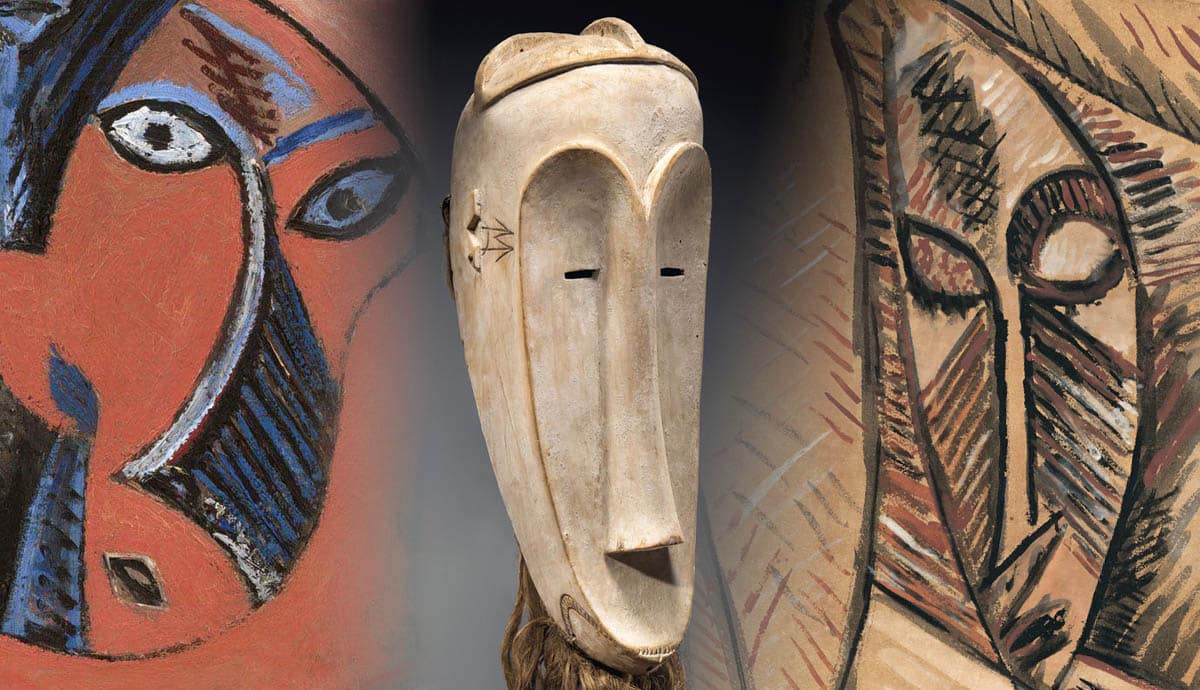

The faces of the two central figures were inspired by Picasso’s interest in the frozen, archaic-like sculptural busts of his native Iberia, while the woman in the top right corner resembles the heavily stylised masks of the Dan tribe of the Ivory Coast. Typically used for protection and as a way to communicate with spirits, Dan masks are considered sacred and can be distinguished by their high foreheads, pointed chins, and pouting mouths. In the lower right of the painting, Picasso paints a woman whose face is defined by its triangular nose and inverted eyebrows. Her geometric features show striking resemblance to a Mbuya Mask of the Pende people, typically used to signify the end of circumcision rituals.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon signified a radical break from the naturalism that had defined Western art since the Renaissance, derailing notions of what art was supposed to look like. Picasso’s two-dimensional women were seen as unfeminine, their confrontational demeanor a complete departure from the traditional depiction of female beauty. The work was received negatively by artists and critics alike, and its menacing sex workers were seen as promiscous and unfit for Paris salons. Picasso rolled up the canvas, considered scandalous even amongst his innermost circle, and stored it in his studio for years to come.

Over the next few years, Picasso continued to borrow from African art, producing a series of drawings, watercolors and sculptures in which he kept reducing facial features to simple geometric shapes in the style of Western and Central African aesthetics. In Head of a Woman (Study for Nude with Drapery), for example, he heavily contoured the subject’s face and created volume by using heavy, shadowed cross-hatching in several directions.

These experiments led Picasso, along with George Braque, to Cubism — the radical movement that emphasized the distinction between painting and reality. African art’s use of simplified forms and fragmented perspectives inspired the artists to abandon the realistic modeling of figures, refuting long-standing notions that art’s purpose was to imitate the natural world. Cubism was monumental in its impact, and became the starting point for many abstract movements such as Futurism, Constructivism, and Neo-plasticism.

Denying African Influences and Picasso’s Art

According to the Nasher Museum of Art, Picasso started collecting African masks, sculptures and musical instruments soon after his first visit to the Trocadero, amassing over one hundred works by the time of his death. A photograph taken by his son Claude in 1974, a year after the artist’s death, shows the extent of his African art collection. This collection was later dispersed to various family members, sold at auctions, and donated to museums.

While art historians tend to agree that there are striking similarities between Picasso’s work and art coming from the African continent, many retain that his borrowing from these cultures was not necessarily intentional. While Picasso acknowledged the initial impact African art had on his vision as an artist, he later denied that his work was inspired by it.

When it came to explaining the stylistic choices he made when painting the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, for example, Picasso made sure to emphasize the Iberian, rather than African, nature of the work. While this was partly due to the artist’s extremely patriotic nature, it also begs the question: did Picasso merely appropriate African visual culture for his own artistic gain, with little to no regard for the cultures he was drawing inspiration from?

According to the postcolonial scholar Simon Gikandi, Picasso was infatuated with the idea of what he considered primitive and tribal, but there is very little evidence that he showed interest in Africans as people and producers of culture. Although the artist was open about the spiritual force he experienced when he first encountered African objects at the Trocadero, he also expressed his irritation at the influence the continent had on him.

Gikandi argues that while art history acknowledges Africa played a part in the development of modernism, it is just as quickly “dispatched to the space of primitivism, a place where it poses no danger to the purity of modern art.”

The contribution Picasso made to the development of Cubism and Modernism is undeniable. But when we examine these critical moments in the history of art, it is crucial to contemplate the countless ways in which African artisans provided unprecedented ingenuity and monumentality to the artist’s work. Picasso’s radical use of two-dimensionality, fierce geometry, and flat planes was only possible because African sculptors and carvers had been mastering the art of abstraction for centuries. Rather than study Europe’s adoption of Africanicity as merely another avant-garde gesture in the timeline of Western art history, perhaps it is time we let the artworks that inspired a movement take the center stage.