Orientalist photographs portraying exoticism proliferated throughout 19th-century Iran. The stereotypical daguerreotypes depicted the Middle East as a fantasyland, indulgent in erotic pleasures. But Iran heeded its own perception. Under leader Nasir al-Din Shah’s guidance, the country became the first to adopt the term “self-orientalization.”

The Origins of Orientalism

Orientalism is a socially constructed label. Broadly defined as Western representations of the East, artistic applications of the word often consolidated ingrained biases regarding the “Orient.” At its root, the phrase connotes the inscrutable European gaze, its attempt to subordinate anything viewed as “foreign.” These notions were particularly prevalent in the Middle East, where cultural differences marked a stark divide between societies like Iran and the current Western norm.

Still, Iran presented its own unique take on Orientalism. Implementing photography as a new means of aesthetic delineation, the country utilized the blossoming medium to self-Orientalize: that is, to characterize itself as “the other.”

How Photography Became Popular in Iran

Iran made a powerful switch from painting to photography in the late 19th century. As industrialization overcame the Western world, the East tailgated close behind, eager to enact its own self-fashioning. In the process of creating a new national identity, the Qajar Dynasty – the country’s ruling class – aimed to separate itself from its Persian history.

By then, Iran had already been notorious for its tumultuous past: tyrannical leaders, constant invasions, and repeated depletion of its cultural heritage. (Once, a monarch gave a British nobleman jurisdiction over Iran’s roads, telegraphs, railways, and other forms of infrastructure to support his lavish lifestyle.) As poverty and dilapidation struck the vulnerable region, the beginning of the 19th century appeared no different. Until Nasir al-Din Shah took the throne in 1848.

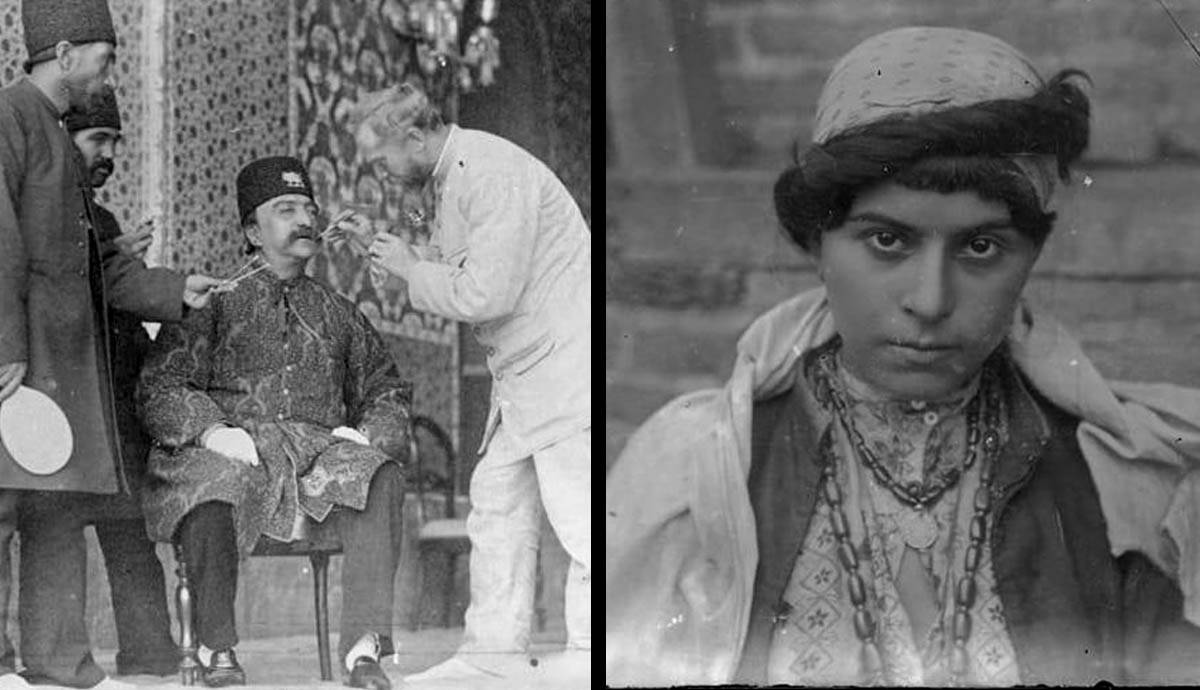

Visual reinforcement would prove the first step to solidify Iran’s shift toward modernity. Nasir al-Din Shah had been passionate about photography ever since the first daguerreotype was introduced to his father’s court. In fact, the Shah himself is lauded as one of Iran’s first-ever Qajar photographers — a title he’d carry with pride for the remainder of his rule. Soon, others followed in his footsteps. Attempting to adapt Iranian tradition to Western technology, Nasir al-Din Shah often commissioned daguerreotype portraits of his court in addition to executing his own photoshoots.

Among the popular photographers of the time Luigi Pesce, a former military officer, Ernst Hoeltzer, a German telegraph operator, and Antoin Sevruguin, a Russian aristocrat who became one of the first to establish his very own photography studio in Tehran. Many were mere painters keen enough to convert their craft. In contrast to an idealized painting, however, photography represented authenticity. Lenses were thought to only capture verisimilitude, a carbon copy of the natural world. Objectivity seemed inherent to the medium.

Iranian daguerreotypes emerging from the 19th century wandered far from this reality, however.

History of the Daguerreotype

But what is a daguerreotype? Louis Daguerre invented the photographic mechanism in 1839 after a series of trials and errors. Using a silver-plated copper plate, the iodine-sensitized material had to be polished until it resembled a mirror prior to being transferred to the camera. Then, after exposure to light, it was developed via hot mercury to produce an image. Early exposure times could vary between a few minutes to a whopping fifteen, which made daguerreotyping nearly impossible for portraiture. However, as technology continued to evolve, this process became shortened to a minute. Daguerre officially announced his invention at the French Academy of Sciences in Paris on August 19th, 1839, highlighting both its aesthetic and educational capabilities. News of its inception disseminated quickly.

Photography inhabits a strange paradox somewhere between subjective and objective. Prior to its adaptation in Iran, daguerreotypes had been used primarily for ethnographic or scientific purposes. Under the Shah’s creative vision, however, the country managed to elevate photography to its own art form. But apparent realism doesn’t necessarily equate to veracity. Though claiming to be objective, Iranian daguerreotypes created in the 19th century were quite the opposite. This is mostly because there’s no singular version of existence. Ambiguity allows individuals to place their own meaning in an ever-evolving narrative.

Most pictures taken during Nasir al-Din Shah’s reign enforced the same stereotypes Iran originally sought to subvert. To no surprise, though photography’s imperialist undertones date back to its inception. Initial applications of the medium occurred in the early 19th century, as European countries sent emissaries to Africa and the Middle East with instructions to document geological ruins. Orientalist travel literature then spread rapidly, detailing firsthand accounts of treks through cultures far removed from the Western way of life. Recognizing Iran’s potential for future investment, Queen Victoria of England even gifted the country its first-ever daguerreotype in an effort to maintain colonial control, further exemplifying its politicization. Unlike written accounts, photographs were easily reproducible and could convey infinite possibilities for redesigning Iran’s image.

Photographs From 19th Century Iran

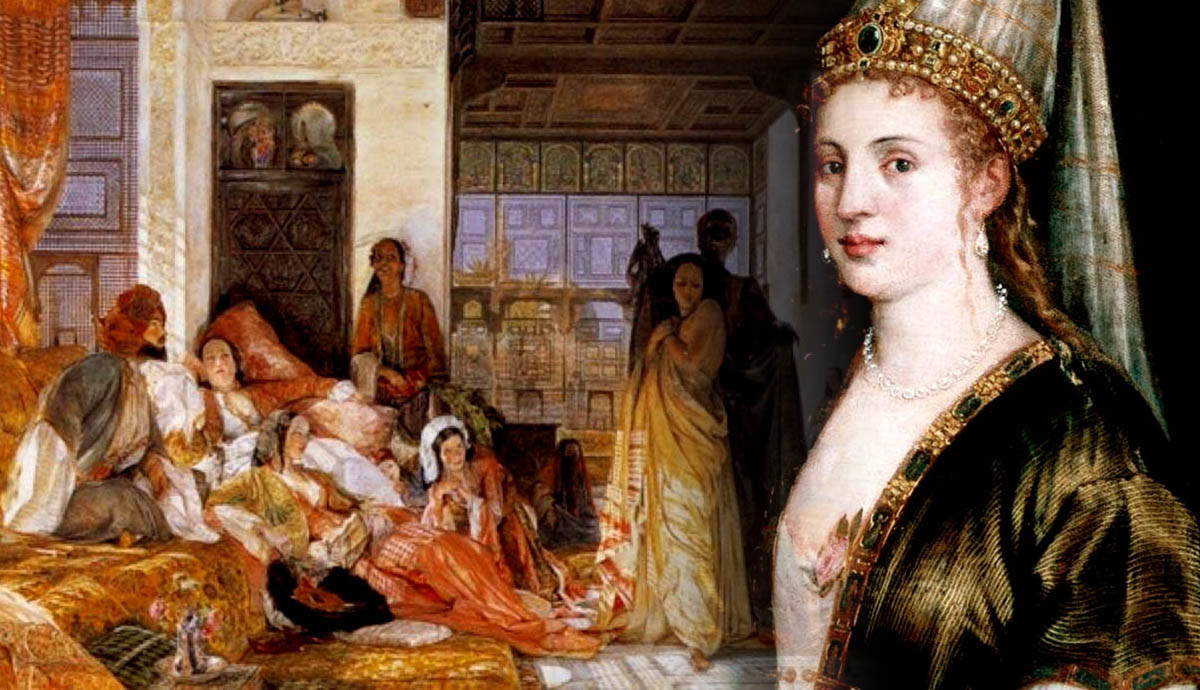

Some of the most scandalous Iranian daguerreotypes depicted the particulars of harem life. Known in Islam as a separate chamber for the wives of the household, this previously private space had been rendered public with the help of photographers like Antoin Surverguin. Though the harem had always been the subject of Western fascination, actual photographs of the space had yet to be revealed.

Alluding to Orientalist paintings like Frederick Lewis’s Harem, Sevruguin’s work also portrayed Iranian women as the object of Western desire. His intimate photograph Harem Fantasy, provides a quintessential example of this seductive concept. Here, a scantily dressed woman gripping a hookah peer directly at the viewer, beckoning us to explore her private oasis. By doing so, she invites the Western male gaze to conceive his own fantasy about her harem. Subjective experience centered this supposed “nonpartisan portrayal.”

Nasir al-Din Shah himself also played a role in Iran’s eroticization. With a strong penchant for photography, the ruler continuously produced harem daguerreotypes depicting him as grandiose and all-powerful. For example, in Nasir al-Din Shah and his Harem, the stern Shah towers above his sensually posed wives.

Locking the viewer’s gaze, he supports prejudices, presuming The Middle East an unconventional and sexually liberated landscape ruled by an Orientalist despot. As the Shah successfully solidifies his image as the sober sultan, his wives become an end goal for a voyeuristic pursuit. Yet even in their antiquated compositions, his wives emanate a spirit that is palpably modern. Rather than appearing stiff like various other daguerreotypes from this period, the women read as confident, and comfortable in front of a camera. This revealing photograph had been specifically staged for European consumption.

The Shah’s private daguerreotypes also upheld similar ideals. In a personal portrait of his wife titled Anis al-Dawla, the sultan masterminded a sexually charged composition through subtle sleights of hand. Reclining with her elaborate blouse slightly open, his subject exudes indifference through her deadpan expression, seemingly devoid of life.

Her disinterest clearly signals she’s grown tired with the tedium of harem life. Or, perhaps her disdain stems from the permanence of the medium itself, its tendency toward uniformity. Either way, her passivity allows for male viewers to impose their own narratives. Like other Eastern women before her, the Shah’s wife becomes an interchangeable template for Oriental lust.

Even beyond the royal court, ordinary photographs of Iranian women also embodied these stereotypes. In Antoin Surverguin’s Portrait of a Woman, he portrays a female dressed in traditional Kurdish garb, her wistful gaze diverted toward an immeasurable distance. Her foreign clothing immediately signals a sense of “other.” As does the subject’s specific pose, which recalls its painting predecessor, Ludovico Marchietti’s Siesta.

By following this artistic lineage, Surverguin successfully situated his work among a larger body of Orientalist work. And, inspired by Baroque artists like Rembrandt van Rijn, Sevruguin’s photographs often demonstrated a dramatic air, complete with moody lighting. It’s difficult to ignore the inherent irony: Iran drew inspiration from its outdated past in an effort to create a modern national identity.

Why Iran Self-Orientalized

Having already internalized Orientalist discourse, the Shah likely hadn’t noted any prevailing contradictions. Many Qajar historians have described him as a “modern-minded” leader, alluding to his status as one of Iran’s first photographers. He’d been interested in Western technology, literature, and art since adolescence. It’s no wonder, then, that the Shah retained this aesthetic vocabulary when he regularly photographed his court later in life.

The same can be said for Antoin Sevruguin, who undoubtedly encountered a vast database of European tradition prior to arriving in Iran. Both photographers present a telltale example of the West’s dominance over Iran. Like a catch twenty-two, lack of exposure to other forms of media disallowed Iran to find a valuable source of inspiration.

Power Struggles in 19th-Century Iran

Iran’s Orientalist daguerreotypes also played into a larger system of hierarchal authority. At its very core, Orientalism is a discourse of power, founded on exotic exploitation. Europeans utilized the concept as a means of justifying foreign intervention and asserting supremacy, strengthening fictitious generalities in the process. And, whether alongside his wives (or in his extremely opulent bedchambers), Nasir al-Din Shah ultimately used photography as a means of magnifying his monarchal superiority.

His daguerreotypes spread beyond their simulated compositions toward a higher end of politicization. They simultaneously strengthened his image as an archetypal leader, while also mimicking (and thus perpetuating), Western notions of the “Orient.” Still, the fact that both an “oriental” and an “orienteur” fell victim to Orientalism’s ubiquity truly indicates the scarcity of accurate information surrounding Eastern culture during the 19th century. Furthermore, the topic raises questions regarding the nature of aesthetic authenticity.

An image’s importance depends on its use. Iran’s daguerreotypes were purposefully orchestrated with specific objectives, often representative of individual identity. From power relations to simple visual expression, eroticism, and even vanity, 19th- century Iran popularized the use of photography to bridge a gap between the East and West.

Inscribed within these representations, however, we find records of an enigmatic lineage: on the forefront of new media, still clinging to its antecedent. Yet this cultural consciousness paved the way for an emerging sense of independence. Following the reform that swept the country during this century, even the Iranian people began to feel a switch in perspective from subjects (raʿāyā) to citizens (šahrvandān). So, in some ways, Nasir al-Din Shah did succeed in his cutting-edge reform.

Orientalism still continues to occupy today’s contemporary world. 19th century Iran may have utilized daguerreotypes as a means of aesthetic exposure, but its Orientalist undertones nevertheless allowed the West to politicize its exoticism. Rather than constantly crusading against these ideologies, it’s imperative to critically examine their origins.

Above all, we must persevere to distinguish between alternative versions of history, taking each binary as a piece to a larger puzzle. With its daguerreotypes being increasingly examined by present-day scholars, 19th- century Iran has left behind a rich cultural database awaiting our exploration. These decadent snapshots continue to tell the story of a unique civilization now long gone.