Diocletian was a formidable emperor who ended a period of turmoil for the Roman world. Known as a great reformer with a harsh personality, he garnered respect where others failed miserably. Born in 244, in the Balkans, Diocletian grew up in turbulent conditions with little government or stability.

Just before he was born, the Roman Severan dynasty had granted undue power to the army. As a result, almost anyone popular with the troops could declare themselves emperor. In 235 when the last Severan emperor Alexander Severus was assassinated all hell broke loose. One man after another was raised by the legions and promptly murdered.

Before Diocletian: Political Anarchy

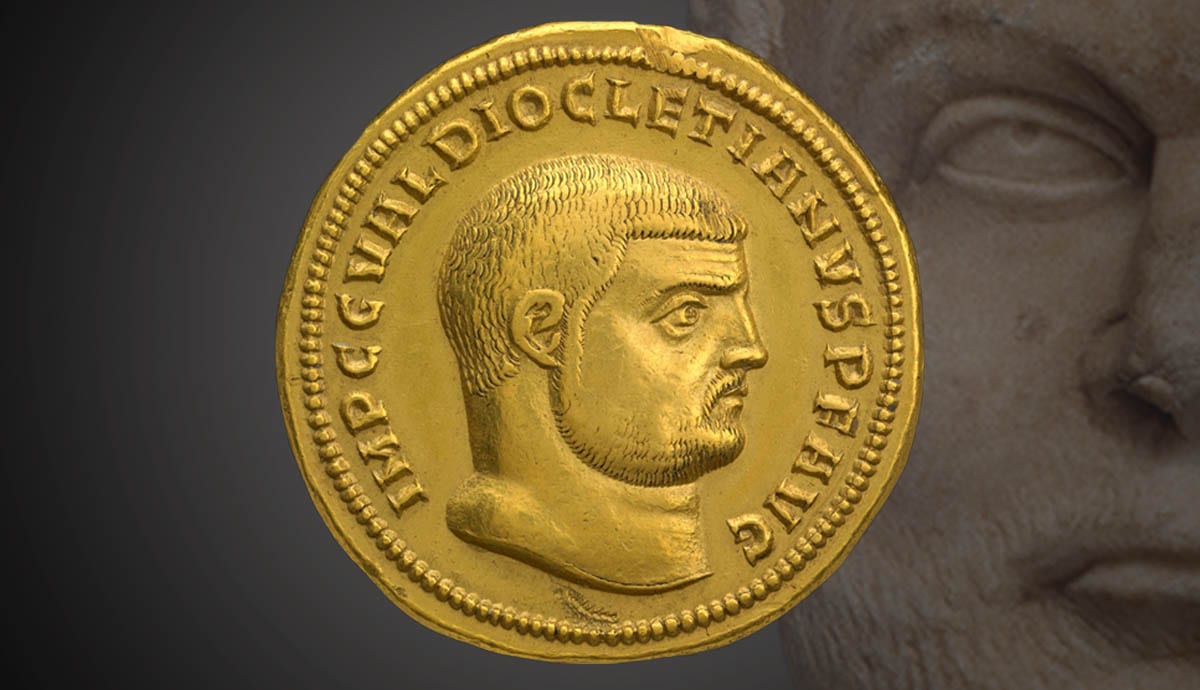

During the 3rd century AD, Rome experienced a period of prolonged anarchy which almost destroyed the Empire. During a 50-year period, there were at least 60 claimants to the throne and many emperors ruled for only a couple of months. There were so many wannabe emperors at this time that historians are still unearthing coins minted by unknown claimants.

The crisis reached its zenith when Britain and France broke away to form the Gallic Empire, and the Palmyrene Empire conquered large parts of the Roman East. Although the worst of the damage was repaired by the emperor Aurelian, by the time Diocletian was declared emperor, Rome was still facing internal rebellions, barbarian incursions, and multiple claimants to the throne. The Roman Empire had become a shaky shell of its former self.

Rise To Power: The Dyarchy

Diocletian’s rise to power was typical of this period. He was a strong military commander, popular with his troops, and was proclaimed emperor by his legions in Nicomedia (modern Turkey) in 284. Diocletian knew that being proclaimed emperor was incredibly dangerous; the vast majority of emperors were assassinated not long after they were raised. He had to act quickly to build a power base.

Upon defeating the army of another military strongman and son of the last emperor, Carinus, Diocletian immediately appointed a co-emperor, Maximian. It was unusual for an emperor to appoint a colleague that was not related to them, but Diocletian chose Maximian based on merit.

Maximian had a distinguished military record and was sent West to subdue dangerous rebellions brewing there, while Diocletian tackled the East. The pair would have to contend with many other claimants to the throne before they could rule safely. They established a temporary dyarchy, and Maximian was made an Augustus, his power second only to Diocletian’s.

The Dominate Of Diocletian: Ruling With An Iron Fist

Diocletian’s rule, and the period that followed it, is sometimes referred to as the dominate, because of the authoritarian character of the monarchy at this time. Although to modern readers and democrats this may sound terrible, it must have seemed necessary in a period of chaos.

The emperorship as an organ of state and respected position had degraded to nothing. To ensure he wasn’t vulnerable Diocletian had to make certain people believed power truly resided in his hands and that it could not simply be taken from him. His ability to craft a powerful image of himself as a Godlike ruler was extremely effective, and as a result, he was able to hold power for twenty years.

In many ways, his rule was the precursor to that of early medieval kings, and he broke many taboos surrounding kingship for the Romans. Emperors had long taken part in a charade in which they pretended not to be autocrats. They referred to themselves simply as “first citizens.”

Diocletian took a different approach. He wore a diadem, a symbol of royalty emperors never dared to wear. His subjects were required to kneel in his presence. Rigid court ceremonial was introduced, such as kissing the hem of the emperor’s robe. Access to the emperor was increasingly limited. He demanded to be called, “Lord and Master,” and “Lord and God.” Artistic conventions in this period shift quite dramatically towards authoritarian portrayals of the emperor, who is shown towering over tiny courtiers. Ordinary people were banned from wearing purple, which became the preserve of royalty. Jewels and silk became part of the elaborate luxury and pomp of imperial court ceremonial.

Doing Things Differently: The Rule Of Four

In spite of his tyrannical reputation, one of Diocletian’s real strengths was knowing that true leadership requires careful delegation. His rule is known to history as the tetrarchy, or rule of four.

The empire at this time stretched from Northern England to Syria, Germany to the Sahara, and parts of the empire had split off during the general anarchy of the military emperors. Under Diocletian’s rule, they would attempt to do so again. The usurper Carausius tried to get Gaul and Britain to break away, and Domitianus did the same in Egypt.

He appointed two more junior emperors, and the four men went in four different directions in order to clear up the last of the rebels, usurpers, and invaders. The senior emperors officially adopted their juniors. Their families intermarried to create strong bonds, and edicts, coinage, and statuary showed displays of unity and brotherhood.

In theory, the junior emperors could take over upon the death or retirement of the senior emperors and appoint new juniors in their place. This was an attempt to create long term stability for Rome, although it had limited success in the face of personal ambition.

Breaking The Power Of The Provinces

Diocletian’s biggest challenge was dealing with the structural problems that had brought the empire to its knees. He more than doubled the number of provinces, which were in turn broken into groups of 12 dioceses, and four prefectures. He recognized that by clipping the power of the provinces, very few people would be powerful enough to challenge him. More people held positions of rank over smaller less powerful areas. This effectively got rid of the 3rd-century problem of too many competing generals with large armies.

He also took the major step of further divorcing military and civil offices at the provincial level. Soldiers would no longer have the standing in the local community they once had, and provincial bureaucracy was expanded greatly to deal with the reality of empire.

In addition to quelling the power of the generals, he made the army more effective. The tetrarchs ensured the army’s main role was simply to keep the borders safe. The number of troops was shored up, forts were constructed, and conscription was introduced to make certain Rome would not be vulnerable to the pressure it faced at its borders: East, West, and North.

Hyperinflation And Struggle For Stability

One of the toughest struggles Diocletian faced during his reign was hyperinflation. In a mistake that would happen many subsequent times throughout history, Septimius Severus had a bright idea for making more money. What if he added more worthless metals to the silver denarius, and therefore minted more coins? As a result, Roman currency became more and more worthless, and what followed was a period of hyperinflation.

Many successive emperors debased the coinage further. Eventually, the silver content was reduced to a thin wash on the outside of the coin. By the time Diocletian came to the throne a barter economy had become the norm in many places.

One of Diocletian’s ideas to fix the economy was “the Edict of Maximum prices,” an extraordinary document that attempted to list every item people bought regularly and the maximum people could charge for it. Many people flouted this decree and it appears not to have worked, but he was the only emperor, apart from Aurelian, who had tried to find a working solution to the economic meltdown.

He also realized that diluting the coinage had caused the problem and struck new gold and silver coins to combat inflation. Although he was not able to solve the Roman Empire’s economic problems, inflation began to slow. His successors would revisit his ideas with more success and Constantine would introduce the gold solidus, a pure gold coin that became “the dollar of the middle ages.”

Tyranny And Christianity In The Roman Empire

Diocletian’s rule had a dark side. The emperor was seen as a tyrant by many people, not least because he hated the growing sect of Christians in his empire. He was concerned with stability; he wanted to root out the causes of Roman decline. Religious reasons were top of his list. Christianity was experiencing a boom in popularity, perhaps in part as a response to dark times. He believed the turn away from Jupiter and the other Roman gods, who traditionally protected the state, might have led to divine disfavor.

Diocletian had a reputation for brutality. When he laid siege to a usurper emperor in Egypt, he asked that his men keep killing until blood came up to the knees of his horse. He took the same approach to Christianity. Scripture was burnt, and church gatherings were forbidden. Many were killed. All citizens were required to sacrifice to the imperial cult to prove their loyalty. Later, Christian commentators would speak of Diocletian with great hatred.

Emperor Diocletian And His Legacy To The Roman Empire

Diocletian was the only Roman emperor to voluntarily retire. He moved into his palace and apparently spent the rest of his life gardening.

Historians are divided on Diocletian’s legacy. The success of the tetrarchy was mixed. The smooth succession he had hoped for with his junior emperors did not last. Although the method he used for breaking provinces among multiple emperors would continue in various forms, the temptation for emperors to install their children as their co-rulers proved to be too great.

Rome would never have an internal conflict on the scale of the 3rd century again. Diocletian’s military reforms served their purpose and kept Rome stable. Furthermore, he established peace with Sassanid Persia which would last 40 years. Constantine the Great would keep and reintroduce many of his tactics and reforms, creating a strong empire with a highly organized rulership.

Although he had authoritarian tendencies and was hated by Christian writers, Diocletian’s political acumen put him head and shoulders above any emperor in the previous century. Most of his successors would copy his dictatorial style of leadership in an attempt to emulate his hard-won stability.

Diocletian resuscitated Rome, and because of his efforts, the empire would carry on until the 5th century. So great was his rule that when trouble started brewing, people begged him to come out of retirement. He responded that he would rather live in peace tending his cabbages.

Less known than the emperors of the Roman golden age, Diocletian is underappreciated in the public’s popular imagination and should be recognized for the towering figure he was.