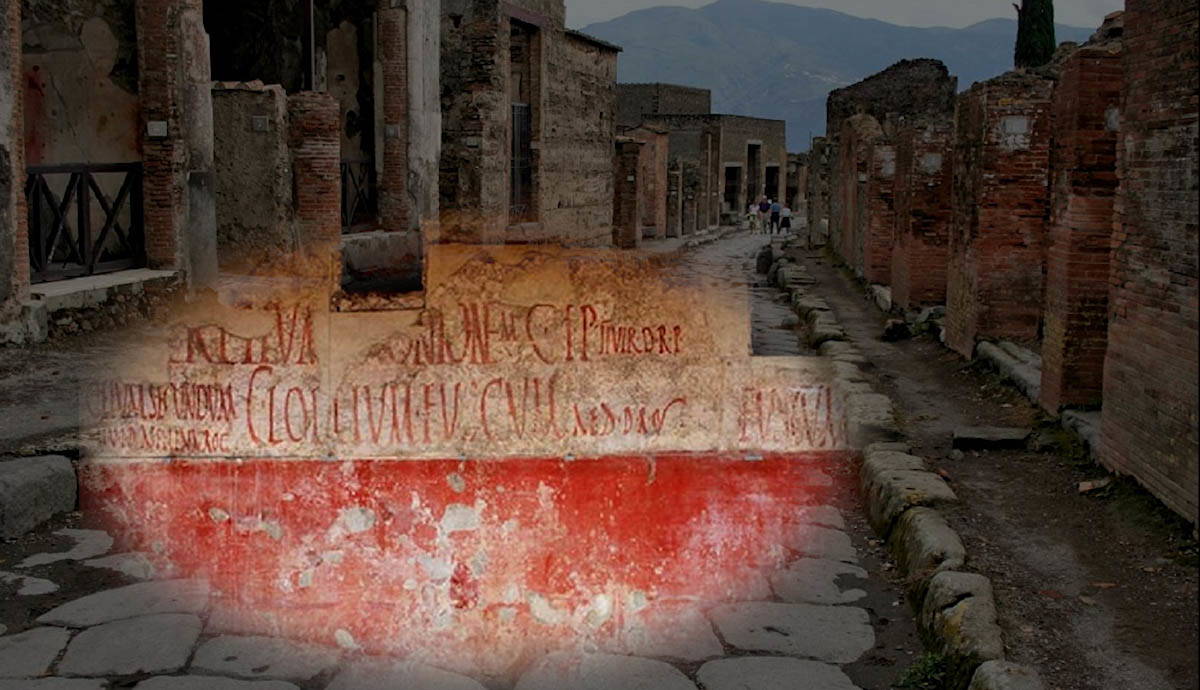

For as long as humans have existed, they have sought to leave their mark on the world around them. Likewise, for as long as human-made structures have existed, there has always been someone ready to draw, write or otherwise carve something into it. Graffiti has existed across the entirety of our history, across nearly every culture to have existed. However, it’s important to remember that the context in which people create graffiti is often different from today. In the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, some of the most beautiful examples of Roman paintings have survived, near-perfectly preserved by cataclysmic events, alongside other, less renowned and far cruder remnants of public graffiti art across the cities’ many walls.

Street Paintings: Graffiti in a Roman Context

Before actually looking into any examples of the rather crude and vulgar examples of street art in Pompeii and Herculaneum, it is important to know how and why they were written. Obviously, given the huge number of graffiti that has existed across history, these examples in Ancient Rome are hardly unique in their existence. It should be known, however, that graffiti in general was not as frowned upon in Roman society as it might be today. This is because of two important aspects of Roman culture; firstly was that people were expected to try and leave their mark on the world. While this might seem obvious, Roman society placed a great amount of emphasis on a person’s deeds, status as well as their ability to be revered and remembered. As such, Roman graffiti very often includes the names of the authors since their intention was to, quite literally, carve their names into the world.

Secondly was a desire to flaunt status and wealth. Romans often enjoyed lavishing guests and others with gifts, parties, dinners, and other displays of excess just to show off. Oftentimes, when one thinks of methods by which to demonstrate their wealth using a wall, they would think first of Roman paintings or other art. While writing onto a wall might seem an odd way of doing so it should be noted that in the first century CE, only twenty to thirty percent of men, and less than ten percent of women, were considered to be literate. Such an education, as a result, was very much something to be proud of in ancient Rome. Because of this, people, of course, wanted to show it off and, given the scarcity of writing materials and the relative softness of the plaster-walled buildings common throughout many Roman cities, there was ample space to advertise how smart and well educated you were. Often by writing about incredibly vulgar and crude topics.

Roman Graffiti 1: From the Bar/Brothel of Innulus and Papilio, Pompeii

“Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men’s behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!”

[Wilhelm, Z. (1871). Graphio inscripta. In Inscriptiones parietariae Pompeianae, Herculanenses, Stabianae, p.502]

It should come as no surprise that bars and brothels were common places for graffiti to be found, much less some of the most vulgar examples. Even in such a place, someone might think it is an odd thing for someone to put up such an example, using a public wall as a space for their coming out.

Once again though it is important to consider the context in which this was written. One might at first believe that Roman society was more tolerant of homosexuality than many other parts of the world and, indeed, much of even our modern world. This, however, is only half right; curiously, in a Roman context, it was less so the act of homosexuality at all that was perceived in a negative light, but rather one of masculinity versus femininity. Masculinity was praised and seen as something to be admired in Roman society, while femininity was not, often pushed to the margins and discriminated against. Because of this, whether or not a man was homosexual was considered less important than the actual role or position he took during sexual intercourse. Simply put, if a man was seen as being penetrated by another, this was considered to be feminine and thus was seen as inferior by Roman society. However, in the case of our author above, who actively engaged in penetration of another was held to an entirely different standard, as he continued to act in a masculine and acceptable way.

Roman Graffiti 2: From the Suburban Baths, Herculaneum

“Two friends were here. While they were, they had bad service in every way from a guy named Epaphroditus. They threw him out and spent 105 and half sestertii most agreeably on whores.”

As stated before, quite a lot of Roman graffiti revolved around bars, brothels, and other public areas, such as baths, and generally often included boastful messages. While it was true that people often used these public scrawlings to show off their intelligence and literacy, it was also commonly used as a means of shaming others. Many of the examples around the city of Pompeii, especially in public areas, often called out people by name for various acts or shortcomings. In this particular instance, these two unnamed friends in nearby Herculaneum seemed quite unhappy with their server and, instead, decided to find other ways to spend their coin.

It is difficult to give a flat value on just how much a sestertius (plural sestertii) was worth in modern currency, but many examples of costs and wages exist to help give us some context. Pompeii itself had a number of stores and records, which gave some idea as to how much things cost in the city at the time of its destruction. For example, a new shirt was fifteen sestertii, while a loaf of bread cost half a sestertii and a donkey could go for as much as five hundred sestertii. One of the more expensive listed items in the city was that of a slave selling for auction for a total of 6,252 sestertii. In regards to how much people made in that time, the average laborer in Pompeii made roughly two sestertii a day, and low ranking Roman Legionaries made nine hundred sestertii per year at the time.

Roman Graffiti 3: From the Brothel on Vico di Eumachia, Pompeii

“Gaius Valerius Venustus, soldier of the 1st praetorian cohort, in the century of Rufus, screwer of women.

”[Wilhelm, Z. (1871). Graphio inscripta: Vico D’eumachia. In Inscriptiones parietariae Pompeianae, Herculanenses, Stabianae, p. 136]

Once again, a brothel proves a hot spot for bawdy boasting and graffiti from men basking in the afterglow of a night well spent. Here we are given another interesting person to focus on, a man by the name of Gaius Venustus. What makes this particular individual of note was his profession as a Praetorian but more specifically, the position he held as a member of the prestigious first cohort, even giving the name of his superior (century refers to a group of 100 men, with Rufus being their centurion or commander).

The Praetorian Guard is perhaps the single most famous (or infamous) branch of the Roman military to have existed. Formed exclusively of hardened veterans, the Praetorians were originally elite bodyguards for civic and military leaders of the Roman Republic. However, after the ascension of Caesar Augustus in 27 BCE, the Praetorians found themselves shaped into an even more prestigious and exclusive corps of soldiers. Formed into nine cohorts, these men were the personal bodyguards of the Emperor, being the only ones allowed to bear weapons within the innermost heart of Rome and in proximity to the palace. Despite the elite stature, veteran status, and greatly increased wages, the Praetorians were known as incredibly disloyal to their Emperors. During their three centuries in service, they assassinated or replaced just as many, if not more, Emperors than they actually protected. Even among other Romans, the Praetorians were to be feared and often seen with outright contempt, often depicted as imposing if not outright threateningly intimidating figures in most Roman paintings. Perhaps because of their feared reputation, the Praetorian Guard were sent to quell riots in Pompeii in 59 CE, which was possible when our visitor had spent his night at the Vico d’ Eumachia.

Roman Graffiti 4: From the House of the Gem, Herculaneum

“Apollinaris, the doctor, of the emperor Titus, shat well here.”

Romans greatly enjoyed toilet humor in general and were largely unashamed of bodily functions from any orifice. While it was true that Rome pioneered sanitation systems and increasingly made use of internal, public latrines, it appears that the population did not feel obligated to use them. Perhaps due to the smells that were known to fill them or just the inconvenience, many Roman citizens would simply relieve themselves at any convenient location. This was evidently so widespread that graffiti has been found on a Herculaneum water distribution tower, warning of fines and beatings that would be given out should someone found to be defecating in or near the tower.

The intrepid author for this particular “Roman painting” demonstrates that, clearly, even one as wealthy and as prominent as the Emperor’s own doctor could be found needing to relieve himself against somebody’s wall, leaving his mark and shortly thereafter boasting of his visit.

When most people think of Rome, they likely imagine it as a relatively clean or even sanitary place, given the prolific use of aqueducts, public bath-houses, and even some of the earliest recorded examples of plumbing. However, contrary to what most people might imagine, this was very much not the case, according to many examples of public “art”. The text above, allegedly written by a very prominent figure in Roman society, is only one of countless examples which make up one of the more common types of Roman graffiti; that being where someone had defecated.