The American Civil War (1861-65) was primarily about slavery, which caused the South to secede from the rest of the United States in order to preserve the institution. Although the Confederate States of America lost the war and the Union was forcibly maintained, the cultural clash over slavery and treatment of African Americans remained. For a decade, the North and South fought politically over Reconstruction, during which the South was militarily occupied and forced to reform. The culture gap that existed before the Civil War between North and South remained and arguably increased after Reconstruction. The North continued to industrialize, and the South remained largely rural and agrarian.

Cultural Divide Over Slavery

In the thirteen British colonies that eventually became the United States of America, slavery was well-established by 1675. A hundred years later, just before the American Revolution, enslaved people constituted about one-fifth of the population. During the war, Vermont became the first US state to abolish slavery in 1777. By this point, slavery had become far more entrenched in the southern states, which utilized slaves for the hard physical labor of agriculture. In the north, which was more urbanized, enslaved people and indentured servants were more often used as servants or artisans.

The South used slavery on a massive scale to run large plantations, or farms that produced cash crops like cotton and tobacco. As more immigrants to the colonies tended to arrive in the North in cities like Philadelphia and New York City, there was more indentured servant labor available that reduced the demand for slaves. Finally, the North also had more religious denominations, such as the Quakers, who firmly opposed slavery. By the time America won its independence, many people in the North were questioning the morality of slavery.

Efforts to End Slavery (1780s-1840s)

Opposition to slavery increased in the North after the creation of the American republic. Many opposed slavery on moral grounds, while others argued that importing slaves from Africa was causing economic instability. The concern about importing too many enslaved people led to the first federal legislation that substantially limited slavery: a ban on the transatlantic slave trade that took effect on January 1, 1808. It came on the heels of Britain’s abolition of the slave trade the previous year. Unfortunately, the end of the slave trade did little to reduce slavery itself, as so many enslaved people were already living in the American South that the domestic slave trade was booming.

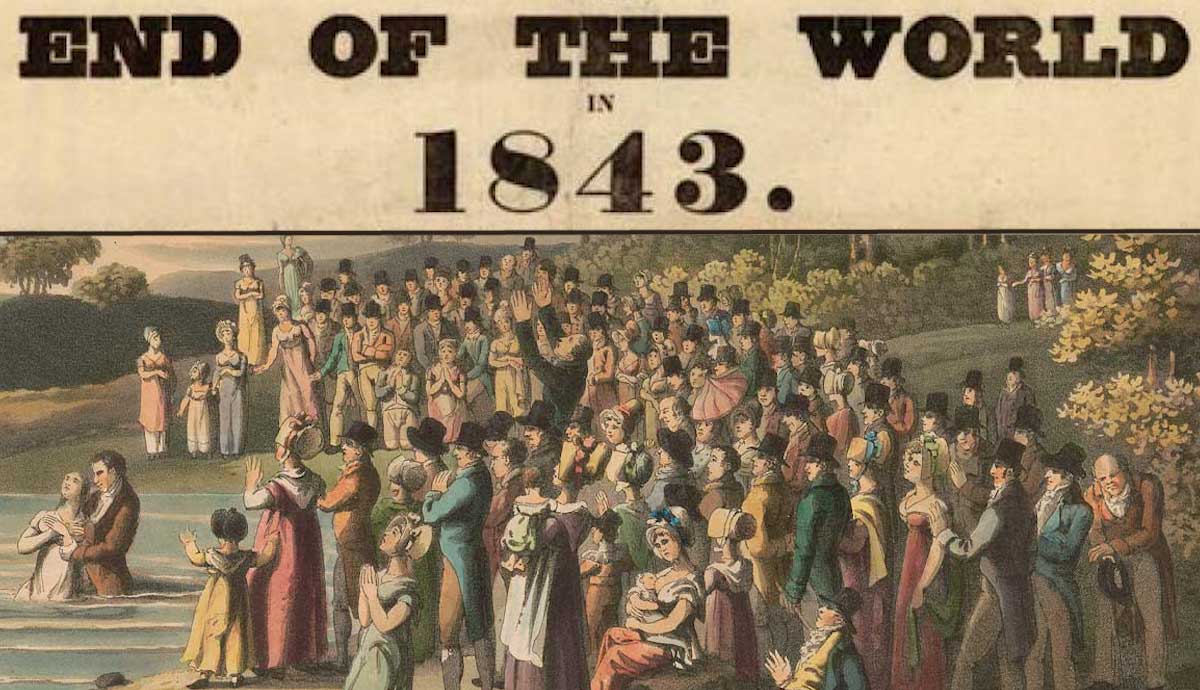

In the 1830s, the abolition movement emerged. The Second Great Awakening religious movement in the United States, coupled with Britain’s abolition of slavery in 1833, set the stage for a widespread movement to demand an end to slavery. In 1833, the Anti-Slavery Society was established. Around that same year, the term “Underground Railroad” became common for the secretive network of homes and businesses that helped runaway slaves escape from the South to the North. While the abolition movement achieved considerable social power in the North, little government effort was put toward abolishing slavery.

Supporters of Slavery Dig In (1848-1860)

While the abolition movement became more popular in the North by the 1840s, the South resolutely dug in on the issue. In 1846, shortly after Texas joined the union as a slave state, the United States found itself at war with Mexico over the Texas-Mexico border. The war was brief, with the US securing victory in 1848 after surprising Mexico by attacking southern Mexico, near Mexico City, from the ocean. Mexico was forced to give up roughly half of its territory in the Mexican Cession, which included the present-day US states of California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado.

The new territory gained in the Mexican Cession prompted intense debates over whether this new territory would be slave or free. A compromise was struck: the new territory would remain free (Mexico did not allow slavery), but the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 locked in Southerners’ “property rights” in regard to slavery. Even if slaves made it to the North, they could be caught and forcibly returned to their masters in the South. In 1857, the US Supreme Court ended the last hope of a federal abolishment of slavery when it ruled that enslaved people, such as Dredd Scott, were not citizens in its infamous Scott v. Sandford decision.

Culture Clash Leads to the American Civil War

The South had been politically successful in refusing to compromise on slavery. Even as the abolition movement gained prominence in the 1830s, Southerners in Congress managed to enact the “Gag Rule” to ban discussion of any bills that would abolish slavery. Although the North was more populous and economically wealthy, each Southern state received equal representation in the US Senate, giving slaveowners political protection. However, the Electoral College, which formally elects the US President after the popular vote, is largely based on state population. By 1860, Northern states could elect a candidate to the presidency without a single Southern elector.

Sure enough, this scenario quickly came to pass. In 1860, Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, who was opposed to the expansion of slavery, won the presidential election despite being barred from the ballot in the South. Swiftly, seven Southern states seceded from the union, beginning with South Carolina. Although the seceding states, which formed the Confederate States of America, had high slave populations, not all slave states seceded. Political maneuvering and not banning slavery during the first two years of the war kept several border states loyal to the Union.

Early American Civil War (1861-62): Preserving the Union

In April 1861, South Carolina militia fired on US Navy vessels coming to resupply Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Thus, the US Civil War had begun! Of immediate concern was how the United States should treat its seceding states. Controversially, President Lincoln focused on preserving the Union between 1861 and 1862, allowing slavery in the border states that remained loyal to the Union and not attacking the Confederacy aggressively. Instead of invading the South in force, the Union retook territories on its margins and tried to use a naval blockade to slowly force it into submission.

The cultural stalemate of the war broke in September 1862 with the Battle of Antietam. Until this point, the South had fought a defensive war, hoping to wear out the will of Northerners. President Lincoln also fought cautiously, not wanting to alienate “War Democrats” in the North who wanted to preserve the Union but not end slavery. When Confederate general Robert E. Lee decided to invade Maryland, ideally to frighten the Union into peace talks, a Union victory in the resulting battle gave Lincoln the opportunity to change the nature of the war. In his famous Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, Lincoln declared that all slaves in states still in rebellion would be legally free on January 1, 1863.

Later American Civil War (1863-65): Abolishing Slavery

The Emancipation Proclamation added a new dimension to the Civil War: abolishing slavery. In addition to giving the Union a moral cause for continuing the war, it also diplomatically isolated the South by reminding two potential European allies of the Confederacy–Britain and France–that the South heavily utilized slavery and was unlikely to win its independence. The Union victory at Antietam also gave Lincoln confidence that the border states would no longer consider secession, meaning he could speak more freely about the ills of slavery. The Union also began recruiting Black soldiers, and up to 160,000 served during the Civil War.

After Antietam, the Union fought more aggressively. An active commander-in-chief, Lincoln replaced the hesitant Union commander at Antietam, George McClellan, with more aggressive generals like Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. This symbolized the North becoming more culturally opposed to Southern rebellion and slavery. Although the Confederacy made one final major attempt to invade the North and scare up peace talks, culminating in the July 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, the Union slowly but surely ground the South into defeat.

The End of Slavery

The US Civil war ended in mid-1865, with Juneteenth being commemorated as the final day of slavery in the country. On June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived at Galveston, Texas to complete the military occupation of the former Confederate states. The troops arrived with a proclamation that all slaves in Texas were legally free. That December, the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution formally abolished slavery nationwide in any form.

However, ending slavery did not mean ending discrimination or racism. Although the North allowed Black men to serve in the army, they were only commanded by white officers. Some white Northerners resented what they saw as a draft being imposed to fight a war to end slavery and engaged in race riots like the New York City Draft Riot. In the South, some had predicted that slaves would remain loyal to their former masters, but this largely did not occur. Most enslaved people in Confederate territory actively sought out the protection of Union forces for the sake of freedom.

Reconstruction Culture Clash: Black Codes vs. Freedmen’s Bureau

The North had won the Civil War but now faced a monumental task: rebuilding the Union. The South had been defeated militarily, and questions swiftly arose regarding how they should be treated. New US President Andrew Johnson, who had replaced Abraham Lincoln in April 1865 following the tragic assassination, was a Southern Democrat who treated former Confederates rather leniently. Southern states only had to ratify the 13th Amendment and apologize for secession to regain self-governing authority. Swiftly, the South began passing Black Codes to strip former slaves of the few rights they had gained.

Northern Republicans reacted angrily to Black Codes and the South’s refusal to respect the rights of newly-free African Americans, as well as the hesitancy of even many in the North to support ideas of racial equality. In 1866, Radical Republicans took control of Congress and possessed a sufficient ⅔ majority in both chambers (House of Representatives and Senate) to take control of Reconstruction in the South. They imposed stricter requirements on Southern states before they would be readmitted to the Union. A new federal agency, the Freedmen’s Bureau, was created to ensure that Blacks in the South were treated fairly by merchants and employers.

Resistance to Reconstruction Intensifies: The KKK

As before the Civil War, the South refused to compromise on fair treatment for African Americans. While Radical Republicans in Congress were able to overturn Black Codes created by state legislatures, Southerners created non-governmental organizations like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) to terrorize African Americans and Republicans and dissuade them from trying to exercise political or economic power. Since former Confederate leaders were prevented from holding political office in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Republicans from up North held administrative jobs in the South and were pejoratively known as carpetbaggers.

When President Andrew Johnson was replaced with Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant, a Civil War hero and staunch Abraham Lincoln ally, after the election of 1868, Grant cracked down on the KKK by declaring martial law in the counties most plagued by racist violence. Aided by a Republican-controlled Congress, Grant used the Ku Klux Klan Act to prosecute KKK members in the South, severely weakening the organization.

Post-Reconstruction: Southern Culture Refuses to Change

Despite the passage of the three Reconstruction Amendments (13th, 14th, and 15th) and the strong efforts of Republicans in Washington DC to protect the rights of African Americans in the South, equal rights were not obtained. Eventually, the political will of Republicans in the North to maintain Reconstruction, which involved the military occupation of the South, dissolved. The Compromise of 1877 saw Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes win the presidency with the help of congressional delegates from the South on the grounds that he remove US troops from the South. He did so, ending Reconstruction in January 1877.

After Reconstruction ended, Southern states enacted racial segregation laws that prevented minorities from using the same facilities, including schools, as whites. These became known as Jim Crow laws and persisted in the South until 1964!

While the South could not re-enact slavery or deny African Americans citizenship, thanks to the 13th and 14th Amendments, respectively, those states did actively seek to override the 15th Amendment by creating complex and biased literacy tests for voter registration. Although the 15th Amendment granted the right to vote to all Black men, voter registration in the South was conducted so that most nonwhite men were denied this right up until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Post-Reconstruction: Northern Culture Shifts Focus From Race to Business

Although the Republican Party fought hard for civil rights, commonly defined as freedom from unequal treatment for marginalized groups, between 1860 and 1876, its focus shifted during the Gilded Age (1865-1890) to supporting economic growth and industrialization. The industries developed during the Civil War became highly profitable and soon captured lots of political support from the reigning Republican Party. Thus, the popular image of the Republican Party as supporting “big business,” often with low taxes and favorable regulations, stems from this era.

Part of the demise of the federal focus on civil rights came from the South’s refusal to change, but part came from Northerners’ own reluctance to support racial equality as well as a shift in federal focus to settling the West instead of pacifying the South. While most Black people, having few resources, remained stuck in the South as sharecroppers, some did move to the North to take jobs in factories. They were often met with hostility from white workers and denied membership in labor unions. Just like Black Civil War soldiers, they tended to be paid less than white workers. There was also residential discrimination, with neighborhoods in Northern cities banding together to prevent African Americans from buying houses. Sadly, this form of discrimination, known as redlining, continued up through the late 1960s.

After the American Civil War: A Long-Term Cultural Shift

Even though the North’s fervor for civil rights waned during the Gilded Age, many in the South realized that glorifying the era of slavery (1619-1865) was politically harmful. As a result, many Southern political and social leaders tried to recast the American Civil War as fought over “states’ rights” rather than slavery itself. This new focus on a supposed struggle between Northern industry and the Southern plantation system, which was a paragon of chivalry and hospitality, became known as the Lost Cause. The Lost Cause romanticized the South and ignored the brutality of slavery. To varying degrees, it remained an integral part of Southern culture until the successes of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.