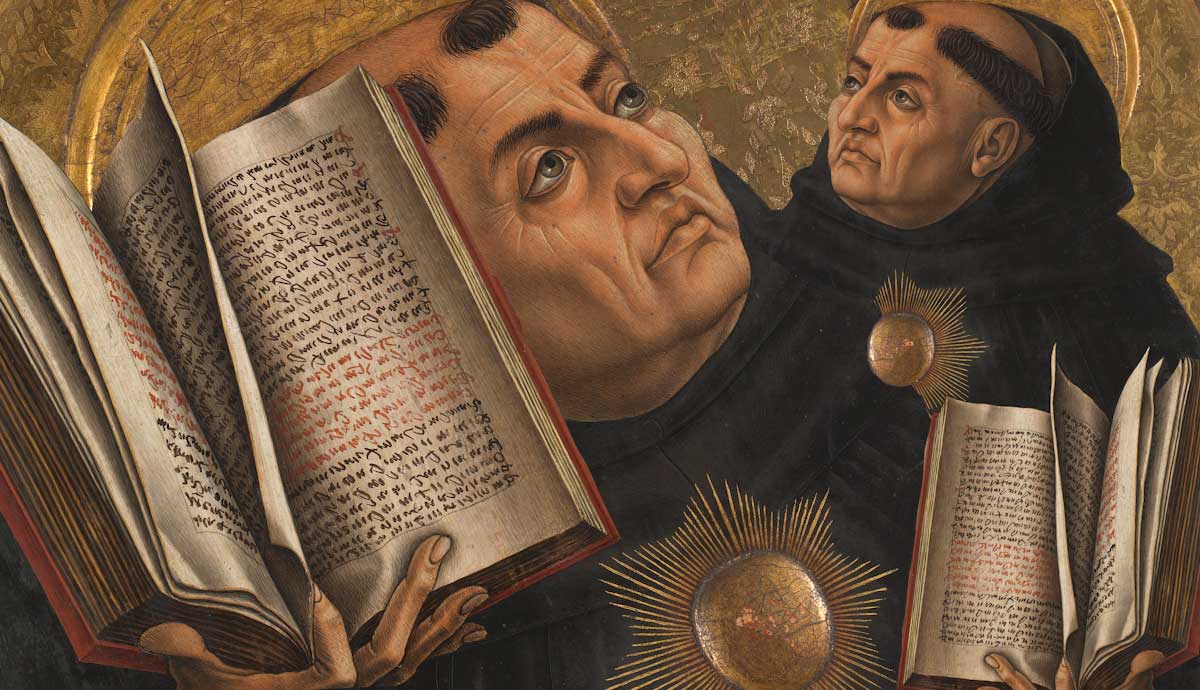

St Thomas Aquinas is one of the most influential theologians to have ever lived, and he remains arguably the single most important intellectual lodestar for the Roman Catholic church today. Moreover, the philosophical approach he developed remains extremely influential among religious and secular intellectuals alike, though what guided his philosophical outlook fundamentally remains the subject of serious debate. In this article, we will take a closer look at several factors that made Aquinas one of the most influential philosophers in the Western tradition.

St Thomas Aquinas: The greatest Catholic intellectual?

Born in 1225, Thomas Aquinas grew up in an intellectual context which was already in the midst of fundamental transformations. Though the popular conception of the mediaeval period, especially the early mediaeval period (or the ‘Dark Ages’) from roughly 400 CE to 1000 CE, tends to vastly exaggerate the degree of intellectual atrophy and general backwardness of the time, it is true that the intellectual activity of most kinds was largely confined to religious institutions, particularly monasteries.

1. He was Educated in the Monastery of Monte Cassino

Indeed, even by the 13th century, monasteries remained an exceptionally important place for scholarship, translation and teaching. St Thomas himself received his early education from the famous monastery at Monte Cassino. Yet at the same time society was changing, and the oldest European universities – including Paris and Naples where Thomas himself studied and taught – had begun to teach secular subjects, as well as theology. These new institutions based their bureaucratic structure on that of trade guilds, rather than that of monasteries.

The standards of scholarship expected were extremely high, with the process to become a master of theology taking St Thomas over ten years to complete. Besides developing new pedagogical practices and raising scholarly standards, these new institutions were also sufficiently separate from the Church such that new religious doctrines could emerge. It would be far too convenient to characterize St Thomas as merely a product of this intellectual environment, or his philosophy as the necessary conclusion of new pedagogical norms.

2. He Was Influenced by Newly “Discovered” Aristotelian Works

For one thing, the availability of new translations of Aristotle’s work as well as new commentaries came largely via the work of Muslim scholars such as Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina, was perhaps the single most significant influence on Aquinas’ philosophical approach, and his thought in general. This also sparked a renewed interest in Greek thought more generally. For another, Aquinas was not the first exceptional theologian of the later medieval period; Peter the Lombard and Albert the Great were both major influences, and the latter actually knew and taught Aquinas.

Nonetheless, Aquinas’ career and his thought can be partially characterised as symbolic of the intellectual climate engulfing Europe at the time. That he is one of the first major philosophers, if not the very first, who embarked on something like an academic career as we would recognise it today, seems like it might be important. The University and the monastery were not, however, the only institutions which Aquinas passed through. He spent an extended period attached to the papal court, serving as papal theologian.

3. St Thomas Aquinas Had Close Political Ties to the Catholic Church

To greatly simplify, it is impossible to understand Thomas’ work without understanding that the Catholic Church which he served was as much a political institution as an intellectual one, and its underlying conservatism has intellectual implications. Naturally, we shouldn’t expect political radicalism from someone with such close connections to one of the main established political institutions of the time, but these conservative tendencies also bleed into Aquinas’ philosophical methodology, which he clearly conceives of as a synthesis of previous thought moreso than a wholly original way of thinking.

The idea of synthesising different intellectual traditions is central to understanding Thomas’ work. The traditional problem which emerges when analysing the work of a religious philosopher or, indeed, the philosophical work of a theologian or other religious figure, concerns how we should define philosophy.

4. St Thomas Aquinas: Philosopher or Theologian?

Few philosophers would wish to say that philosophy is so specific, so technical, so apart from ordinary thinking and ordinary life in general that there is a sharp distinction between the work of a philosopher and all other intellectual activity. So we might think that what we are concerned with, when we ask whether someone is a philosopher or whether someone’s work is philosophy, is a matter of degree. But this seems an dissatisfying approach in itself. Surely there’s more to this question than distinguishing the ‘philosophical part’ of their work from the rest of it?

Moreover, by adopting this way of putting the problem, we are right back to drawing a sharp distinction between philosophy and all other kinds of intellectual activity. One can step back from the problem, and conceive of the difference between philosophy and theology as primarily a matter of disciplinary convenience. One can even define these disciplines in terms of the institutional structures in which their practice takes place, namely by defining theology as the kind of thing which goes on in a theology faculty.

Even if this sounds dissatisfying, there is nothing wrong with this in principle. And even if there are rough distinctions to be drawn between mathematics, physics and chemistry, the way in which border disputes tend to be arbitrated based on the kind of work which happens to go on in mathematics, physics or chemistry departments. Of course, people who consider themselves theologians will always have some sense of the sort of thing theologians do, the kind of work which falls under a theologian’s remit and so forth, but this may not purport to draw a timeless distinction between philosophy and theology.

In practice, the kind of work which happens in a theology faculty, or a philosophy faculty will change with time and is subject to fashion as much as anything. Whatever the appeal of this kind of pragmatic approach to distinguishing theology and philosophy in abstract, in practice it doesn’t solve the issue which St Thomas was concerned with.

5. Aquinas Distinguished Between Theological and Philosophical Understanding

That is, to distinguish the way of knowing which is derived from revelation from the way of knowing which human beings establish on their own. In other words, to distinguish what God teaches us from what we can learn ourselves. Thomas approaches the issue in the following way: “… it should be noted that different ways of knowing (ratio cognoscibilis) give us different sciences.

The astronomer and the natural philosopher both conclude that the earth is round, but the astronomer does this through a mathematical middle that is abstracted from matter, whereas the natural philosopher considers a middle lodged in matter. Thus there is nothing to prevent another science from treating in the light of divine revelation what the philosophical disciplines treat as knowable in the light of human reason”. Here, Thomas draws the distinction between theological understanding, which is understanding in light of divine revelation, and philosophical understanding, which is understanding in light of human reason.

What’s so interesting about this passage is it suggests that theological and philosophical understanding can constitute two different ways of coming to the same answers about the world. The distinction between philosophy and theology which holds that they are interpretive perspectives on the world, not positions from which we create by Aquinas’ claim that even knowledge about God’s nature can be acquired philosophically.

It is difficult to understand that there is still a distinction at work here, when Aquinas holds that – for instance – even the nature of God is itself available as a subject of philosophical enquiry. On first glance, this seems to risk making theological knowledge a subspecies of philosophical enquiry, or even to make it difficult to understand what the point of this distinction is. To view this as a problem suggests we have a fixed view of what philosophy is and should be.

6. St Thomas Aquinas: Philosophy as an Attempt to Understand the World

It is a view worth examining, because its prevalence in Western philosophy from the early modern period to the present day makes it difficult to understand earlier philosophers whose work stands outside of it, as Aquinas’ does. The view in question has two parts. First, there is some suggestion that when one undertakes philosophical reflection, one is to bracket or indeed wholly renounce the beliefs one already holds, insofar as they might otherwise be brought to bear on the philosophical conclusions one comes to. This we might call, as many others have, the Cartesian view of philosophy.

Secondly, and relatedly, there is the suggestion that what philosophy does most of all is allow us to draw firm and (preferably) correct conclusions about specific kinds of things; it is the search for knowledge of these things. Aquinas accepts neither premise. Philosophy, on his account, has to precede from the beliefs one comes to it with in the first place, and so what philosophy is most of all is a method for testing our antecedent beliefs which those who have a variety of beliefs could come to agree on in principle.

This runs against the view of philosophy which says that there is an objectively correct description of reality, one which is perfect no matter what. On this conception, even if this perfect description is hypothetical and forever out of reach, that it is conceivable offers a single standard of evaluation for philosophical enquiry. In Aquinas, we see the seed of a different way of conceiving philosophy, one which has its basis in Aristotle.

Philosophy is an attempt to understand, from the place where one is. The shape of philosophical enquiry is fundamentally intertwined with the intellectual capacities, the experiences and the character of a particular individual. The limits of reason are not objective; if there is such a thing as human nature and its limits, then there is also such a thing as an individual’s nature, and an individual’s limits. It is to this that philosophical enquiry must direct itself. It is from this that Thomas’ version of virtue ethics, his conception of politics, his epistemology and his philosophy in general flows.