This article is about Theodor Adorno’s analysis of Samuel Beckett through his essay about Endgame, one of Beckett’s most influential plays. We begin with a discussion of Endgame and a summary of the play’s style. We then move on to introduce Adorno. One of the major themes of Adorno’s analysis of Beckett is his conception of Beckett’s drama as a repudiation of certain trends in philosophy at the time, especially existentialism.

Beckett’s Endgame

The play which Adorno focuses on when analyzing Beckett is Endgame, probably Beckett’s second most popular play after Waiting for Godot, but often regarded as his best play. Harold Bloom, a very influential literary scholar, deemed it the greatest prose drama of the 20th century (prose drama as opposed to a play written in verse).

It is worth offering a kind of brief summary of what Endgame is like. The reason we cannot simply say what it is ‘about’ is that this is the very subject Adorno takes up in his essay, and it is a question that has no very sure answer, as the uncertainty in said essay shows. Endgame has four characters—Hamm, Clov, Nagg, and Nell. The first two are the main protagonists, while the latter two are Hamm’s parents and live in dustbins. The play is set in a hovel, which itself exists in a kind of unspecified, post-apocalyptic place. Hamm and Clov are explicitly waiting for the ‘end,’ though why and in what form they expect this isn’t clear. Indeed, much of the action in the play is explicitly unclear, and the dialogue is often discontinuous and jarring. Misunderstanding and impotence are the orders of the day. It is a brilliant play, worth reading on its own and for fun (it is quite funny, but very sad). The play itself is not the focus of this article so much as what Adorno has to say about it.

Adorno’s Life and Work

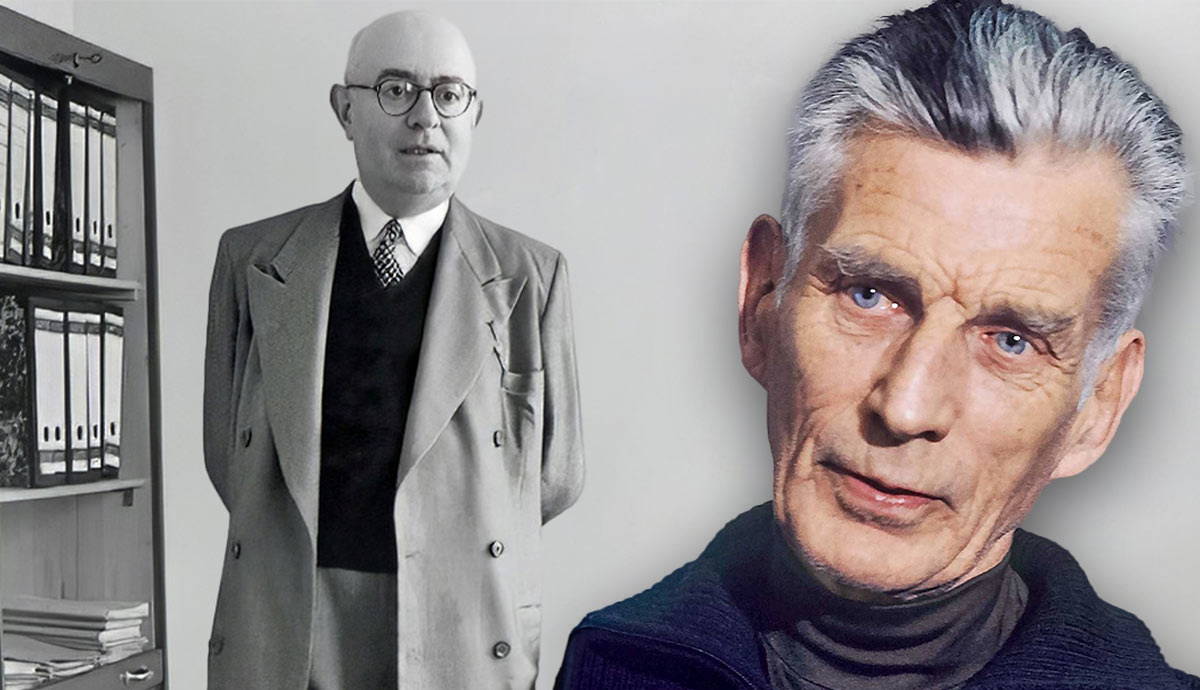

Who was Adorno? Theodor Adorno was a German Marxist, philosopher, and critic of art, music, literature, and culture in general. He was an early member of the famous Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, which was the first research center, institute, or university department explicitly committed to Marxist research.

Adorno was incredibly intellectually omnivorous, and his exceptional range of interests is difficult to reckon with as a whole without a similar familiarity with so much of Europe’s cultural history. His essay on Endgame is similarly hard to untangle, partly because he grounds his analysis of the play in a wealth of receptions of other works of literature and assumes a degree of familiarity with aesthetic movements, philosophical movements, and developments in classical music that the contemporary reader cannot hope to have.

So why read this essay? Well, if you are able to follow much of what Adorno says (and patiently look up the references that elude you), then what this essay reveals is an approach both to the play and to literature in general that remains singular and worth examining in detail.

Making Sense of Endgame

One of the abiding concerns in Adorno’s treatment of Endgame is the meta-critical question: how are we to make sense of a work like Endgame? In other words, when a work of art is itself focused on the destruction of meaning, on the impossibility of figuring things out, getting things right, or saying something that matters, what can a critical response be?

One kind of critical response is evidently unavailable. That is the response to a work of art that is focused on determining what it means. The critic’s task becomes one of reconstruction, offering a kind of synthesis of non-meaning. What Adorno seems to be suggesting is a critical project based on the structure, rather than the transcendent idea, of a work of art: “split off, thought no longer presumes, as the Idea once did, to be the meaning of the work, a transcendence produced and vouched for by the work’s immanence.”

Yet Adorno’s reading of Endgame is deeply enmeshed in existing philosophical and historical debates. For one thing, whereas Beckett has (probably erroneously) been read at times as an existentialist playwright, Adorno takes Beckett’s work as a repudiation of the existentialist movement. This move is characteristic of one of Adorno’s overarching commitments—that works of art should be considered in terms of their socio-historical significance and their contribution to an intellectual milieu rather than as an object in a simple subject-object (reader-book, audience-play) relationship.

But what is, or was, existentialism? This is a difficult question, partly because existentialism is one of those labels which can be applied to a lot of different philosophers, writers, and artists, and yet many of the same do not want to admit to being existentialists. The only major philosophers who identified themselves as existentialists were Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and it was probably they and their disciples who were in Adorno’s line of fire here.

Existentialism

We can offer a sketch of existentialism as Sartre and de Beauvoir thought of it. As we do so, we can fill in some of the ways in which Adorno observes Endgame to be an anti-existentialist work.

Sartre and de Beauvoir believed existentialism relies on four concepts. First, that of engagement—existentialism defends a conception of philosophy that is opposed to a detached, sheerly intellectual perspective on the world. For the existentialist, what we should try to do is make sense of things from a position in the midst of them.

There is a very straightforward connection to be drawn between this element of existentialism and what happens in Endgame. Endgame is relentlessly in the midst of things. We are inserted, with no preamble, into this strange world (parents inhabit dustbins, for example), and things simply happen. These ‘simple’ happenings—these things which occur without much hope of sense being made of them, seem to fly in the face of the very possibility of ever making sense of things. Of course, that is not to say Beckett advocates stepping outside of things and making sense of them from there either; that would be impossible.

Existence and Honesty

Perhaps the most famous slogan of the existentialist movement is ‘existence precedes essence.’ This is a claim about the self and effectively means that we should think of ourselves and others not as constituted by some prefabricated substance but as always in the midst of being created.

We can combine this element of existentialism with what is arguably its core ‘value’—that of authenticity. Authenticity in this context partly refers to a tendency or a willingness to define oneself against or in spite of prevailing social norms. Often terms like ‘urgency,’ ‘moral seriousness,’ and ‘existential purpose’ are associated with this idea.

Adorno discusses Endgame as a work of catastrophe, one in which the consequences of catastrophe on human selfhood are taken to an honest conclusion. Dishonesty in existentialism is one of Adorno’s main bugbears, and it is particularly the failure to take the consequences of the historical moment directly after the Second World War sufficiently seriously that sets Adorno against the existentialist point of view. Adorno sees the events of the 20th century, and especially the Holocaust, as signaling a “new categorical imperative” for human beings, even in a state of unfreedom, to organize themselves so that nothing like the Holocaust could ever happen again.

Adorno on the Relationship Between Philosophers and Artists

This leaves philosophers and artists in the following position: they must not deny the existence of transcendent ethical concepts, including that of the self, lest this nihilism provides the fuel for a similar kind of horror. They must also avoid affirming the existence of transcendent ethical concepts and the utopia they imply, in case it cuts off our critique of the society in which we actually live.

The point for Adorno is that Beckett’s honesty about the ways in which the transcendent self has been shattered is an honest reflection of socio-historical conditions. That isn’t to say that Beckett’s work is only applicable to a certain place and time. Adorno allows that we may have learned that the transcendent self was always broken, but we have learned this in a specific way due to certain historical events.

The final element of existentialism that is relevant to this discussion is the idea of freedom. Existentialism holds that we exist for ourselves and that our ability to represent ourselves to ourselves (that is, to become self-conscious) is a core feature of human life. Endgame, in which characters are constantly moving but only moving within a clearly delineated, confined space, is a rebuke to existentialism in terms of how it shows this claim about freedom to be, even if true, ethically trivial. Freedom cannot be meaningful by fiat. The external conditions, the state of the world at large, are equally as important.