Immortalized in stone and stylus, ancient Egypt dominated the Near East for over three millennia. Here is the entire timeline of ancient Egypt, running all the way from the Old Kingdom to the Ptolemaic Period.

Timeline of Ancient Egypt

| Period | Dynasties | Characteristics |

| Old Kingdom (ca. 2686–2181 BCE) | Dynasties 3–6 |

|

| First Intermediate Period (ca. 2181–2040 BCE) | Dynasties 7–11 |

|

| Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1650 BCE) | Dynasties 11–13 |

|

| Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1640–1550 BCE) | Dynasties 14–17 |

|

| New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 BCE) | Dynasties 18–20 |

|

| Third Intermediate Period (ca. 1070–664 BCE) | Dynasties 21–25 |

|

| Late Period (ca. 664–332 BCE) | Dynasties 26–31 |

|

| Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE) | – |

|

The Old Kingdom

Spanning from the Third Dynasty through the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2686-2181 BCE), Ancient Egypt’s Old Kingdom is most famous for its massive and complex construction projects, namely the building of pyramids commissioned by great names such as Third Dynasty King Djoser, and his architect, Imhotep, Sneferu, the founder of Dynasty 4, and of course the constructors of the Great Pyramids of Giza, Khufu, his son, Khafre, and his grandson, Menkaure. Fun fact: Khufu’s pyramid is actually taller than Khafre’s construction, however, since Khafre built his pyramid on higher ground and at a steeper angle, his appears to be larger!

The Old Kingdom also underwent a series of changes in religious beliefs in the Fifth Dynasty, including the rise of the god Osiris, lord of the dead, and the expansion of the solar cult of Ra. He became worshipped directly by the people through the temples run by priests, which, in combination with their responsibility of facilitating taxes, gave the priesthood a lot of power at the expense of the throne. Eventually, the government was decentralized in the Sixth Dynasty and power fell to local officials. Competing provincial rulers combined with issues of succession, drought, and famine resulted in the decline of the Old Kingdom.

The First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period (ca. 2181 — 2040 BCE), was a dynamic period in the timeline of ancient Egypt, when the rule of Egypt was divided between two competing power bases, one at Heracleopolis in Lower Egypt, and the other at Thebes in Upper Egypt.

Little is known about the Seventh and Eighth Dynasties due to a lack of evidence. The Seventh Dynasty—if it existed—allegedly experienced ‘seventy kings in seventy days’. Dynasty 8 rulers claimed to be the descendants of the Sixth Dynasty kings; in any case it is seen by many as the start of the First Intermediate Period in the timeline of ancient Egypt. Dynasties 9 and 10 were also known as the Herakleopolitan Period; while the influence of these kings never quite measured up to that of the Old Kingdom, they succeeded in bringing a certain amount of order and peace into the Delta region. However, they did frequently butt heads with the rulers of Thebes which resulted in bouts of civil war.

The independent province of Asyut, situated between Herakleopolis and Thebes, rose to power and gained status from a variety of agricultural and economic activities and acted as a buffer during times of conflict between the northern and southern parts of Egypt. During the Eleventh Dynasty, the Theban kings gained the upper hand against the Herakleopolitan rulers and facilitated the movement toward a unified Egypt for the second time.

Middle Kingdom Egypt (ca. 2030 – 1650 BCE)

Mentuhotep II was the first king of the Middle Kingdom, restoring stability after a period of pharaonic weakness and civil war in the timeline of ancient Egypt. His plan was to attempt to emulate the Old Kingdom and was once more regarded as the centralized seat of power, but his subordinate officials retained some of their former power which helped ease the transition from the First Intermediate Period into the Middle Kingdom.

The height of the Middle Kingdom came under the reign of Senwosret III, an eminent warrior-king. He led many campaigns into Nubia to control the southwestern border, and passed laws that further centralized power for the throne. During his later years, he brought on his son, Amenemhat III, as co-regent and eventual successor. Egypt experienced a height of economic prosperity during Amenemhat III’s rule. The throne began to weaken with a series of short-lived kings, the 13th dynasty could no longer maintain control of the country, giving way to a stronger power.

The Second Intermediate Period (ca. 1640 – 1550 BCE)

The decline of Middle Kingdom Egypt meant that the country could no longer maintain its borders, which resulted in the Nubians advancing and occupying the forts.

Meanwhile, a Semitic people called the “Hyksos” entered Egypt and settled at Avaris in the north. They did not control all of Egypt, though, instead coexisting with the 16th and 17th Dynasties based in Upper Egypt. Archaeological evidence indicates that they Hyksos were respectful toward the religion and culture of Egypt, practicing their own customs while also incorporating Egyptian traditions (e.g. combining art styles, adopting the Egyptian royal titulary and pantheon).

Despite this, the native Egyptians became increasingly restless and unhappy with the foreign leadership, and local rulers began to resist Hyksos control through rebellions and warfare. Seqenenre Tao and Kamose, the two final kings of the Second Intermediate Period in the timeline of ancient Egypt fought back against the Hyksos. After Kamose died, his younger brother, Ahmose, kicked out the last of the Hyksos and became the first king of New Kingdom Egypt.

New Kingdom Egypt

New Kingdom Egypt was defined by the desire to widen the boundaries of Egypt. Egyptians attained the greatest amount of territory in the entire timeline of ancient Egypt by extending into Nubia and the Near East.

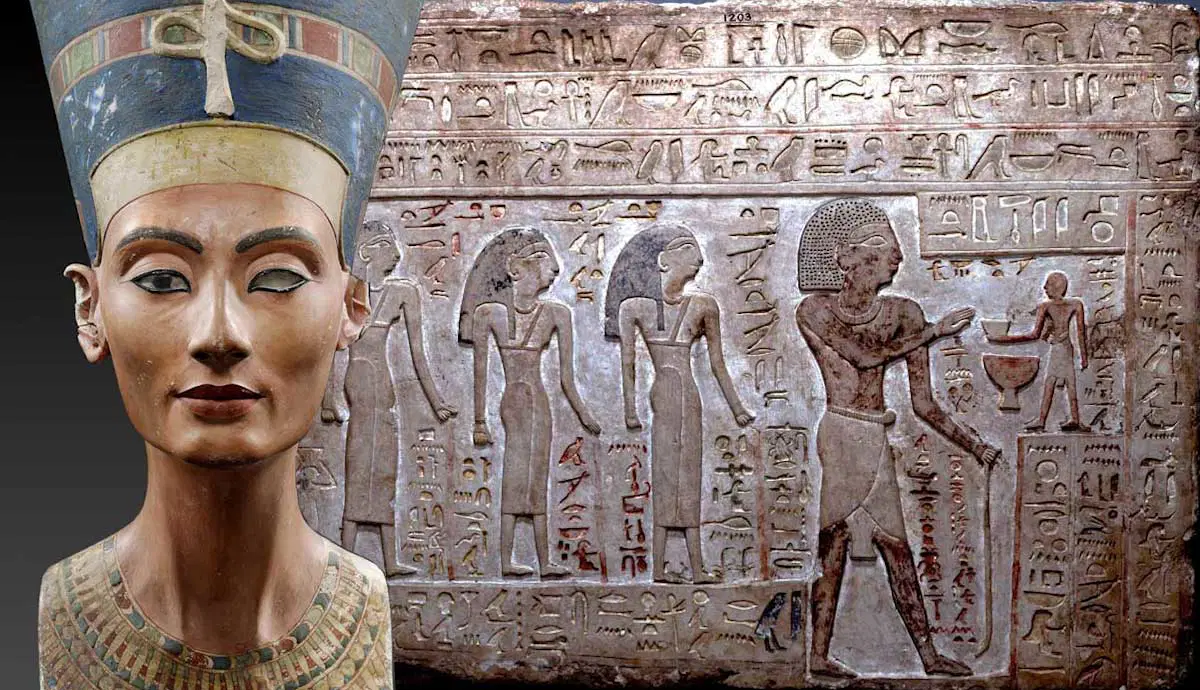

The Eighteenth Dynasty contained some of Egypt’s most famous kings and pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Akhenaten, and Ramesses II. Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s great female kings, mostly concentrated on expanding Egyptian trade and conducting large-scale building projects, while Thutmose III consolidated power through a series of military campaigns. Akhenaten is infamous for his fervent and exclusive devotion to the god, Aten. His neglectful indifference to political and economic matters resulted in the shutting down of temples, the destruction of the Egyptian economy, and the extension of Hittite forces into the Levant. Ramesses II attempted war against the Hittites, but eventually agreed to a peace treaty after an indecisive result.

The heavy cost of military efforts in addition to declining political and economic power resulted in a loss of centralized authority at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, leading to the Third Intermediate Period.

Third Intermediate Period

During the Third Intermediate Period, the Twenty-first Dynasty was characterized by ancient Egypt’s crumbling kingship, as power became split between the pharaoh and the High Priests of Amun at Thebes. Dynasties 22 and 23 were overseen by the Libyan Meshwesh tribe. They established themselves in Egypt around the Twentieth Dynasty, and the kings ruled with a style similar to their Egyptian predecessors, however peace was short-lived due to the rise of local city-states.

The Twenty-fourth Dynasty kings were also of Libyan origin but had broken away from the Twenty-second Dynasty, which led to internal rivalries. This did not escape the notice of Nubia, who led a campaign to the Delta region in 725 BC and took control of Memphis, eventually gaining enough allegiance from the locals to reunify Egypt under the largest empire since the New Kingdom. They assimilated into society by blending Nubian and Egyptian religious, architectural, and artistic traditions. However, during this time the Nubians had gained enough power and traction that they drew the attention of the Neo-Assyrian empire to the east.

Between 671 and 663 BCE, the Neo-Assyrians launched a series of attacks on Nubia, effectively pushing them out of Egypt to seize control of the land. They placed a series of local Delta puppet rulers on the throne, ending Nubian control in Egypt and ushering in Dynasty 26 of the Late Period.

Late Period (ca. 664 BCE – 332 BCE)

At the end of the Third Intermediate Period, Assyria had taken over Egypt and placed several native loyalists on the throne as vassal princes. Unfortunately for Neo-Assyrians, trouble on the home front forced them to leave Egypt to its own devices. The vassal king, Psamtik I of Sais, seized the opportunity to assert his independence and reclaim Egypt as part of Dynasty 26, otherwise known as the Saite dynasty.

Regrettably, this revival did not last long. The Persian Achaemenids conquered Egypt for themselves twice, ruling as foreigners through a satrapy that defined the Late Period. The Saites attempted to rebel against the Persians without much success. Under most kings, many Egyptian traditions either faded or were completely halted. However, the Persian king, Darius I, played things a bit differently. He actually appreciated Egyptian religious beliefs and internal affairs, which earned the respect of the locals. On the whole, though, tensions between the Egyptians and the Persians were high. Rebellions against the Achaemenids occurred relatively frequently; unfortunately, most were unsuccessful, and eventually marked the end of Egypt as an independent nation.

The Persians held onto Egypt until Alexander the Great arrived in 332 BCE. After seizing their capital and surrounding territories, Alexander ran the Persians out and placed his general, Ptolemy I Soter, on the throne.

The Ptolemaic Period

The Ptolemaic Period began when Alexander the Great defeated the Persians in Egypt in 332 BCE. After his death in 323 BCE, his territories were divided up between his generals. Ptolemy won control of Egypt and declared himself pharaoh in 305 BCE. The Ptolemies insisted upon the predominance of Greek and Greek citizens within the empire while simultaneously adopting certain Egyptian traditions and religious beliefs to secure their rule. The Ptolemaic rulers did not force the Egyptians to alter their own culture and belief systems like the Persians did. On the contrary, they actively supported some traditional Egyptian practices and forms seen in their architectural projects, religious practices, and Greco-Egyptian art.

On the other hand, there was never a unified movement to assimilate the Greeks into Egyptian culture. While it was possible for native Egyptians to advance themselves in this new society, Greek citizens were the only ones who could hold positions of power in government and society. Sources of wealth, power, and influence were privileges that really only the Greeks could tap into. Later on when the Egyptians were forcibly drafted into the king’s army to fight and finance their battles, being treated as second-class citizens in their own homeland led to feelings of malcontent and a series of revolts that were never satisfactorily addressed.

The decline and fall of the Ptolemaic Dynasty coincided with (and was due to) the rise of the Roman Republic. Their power waning due to external threats and semi-constant internal assassination plots, The Ptolemies were forced to ally with Rome. As Rome’s power grew, their influence on Egyptian politics and assets grew too. Any coups against the new regime—most famously Cleopatra and Mark Antony—were thwarted, and with their deaths came the official end of the Ptolemaic Dynasty and pharaonic Egypt.