The ukiyo-e art movement started in the 17th century and peaked in 18th and 19th century Edo, current-day Tokyo. The advent and rise in popularity of ukiyo-e were not only about new technical inventions and possibilities but also intrinsically tied to societal development at the time. It is Japan’s first truly globalized and popular mass media type of art production. Ukiyo-e type prints remain extremely praised to this day and many of the most iconic images we associate with Japanese art are born of this movement.

The Ukiyo-e Movement

In the early 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate was established with Edo as its capital, ending a prolonged period of civil war. The Tokugawa shoguns were de facto rulers of Japan until the 19th century Meiji Restoration. The city of Edo and its population size boomed, giving the hitherto bottom dwellers of the society, merchants, unprecedented prosperity and access to urban pleasures. Until that time, most artworks were exclusive and created for elite consumption, such as luxurious grand scale Kano school fans influenced by Chinese painting.

The name ukiyo means “floating world,” referring to Edo’s mushrooming pleasure districts. Started mainly with painting and black and white monochrome prints, full-color nishiki-e woodblock prints quickly become the norm and most widely used medium for ukiyo-e works, assuring both the visual impact and the large production needed for pieces designed to cater to the masses. A finished print was a collaborative effort.

The artist painted the scene which was then translated onto several woodblocks. The number of blocks used depended on the number of colors needed to produce the final result, each color corresponds to one block. When the print was ready, it was sold by the publisher who would go on to advertise the product. Some successful series went through several reprints until such time the blocks were completely worn out and need to be retouched. Some publishers specialized in high-quality prints reproduced on fine paper and expansive mineral pigments offered in exquisite bindings or boxes.

The production and quality of ukiyo-e works produced are generally considered to have peaked at the end of the 18th century. After the 1868 Meiji Restoration, there was a decrease in interest in ukiyo-e print production. However, the domestic shift opposed the rising European interest in Japanese prints. Japan was just opening up to the world and ukiyo-e prints circulated internationally along with other goods. They also had a profound influence on the development of 20th-century modern art in the West.

Popular Subjects Of Ukiyo-e Prints

The primary subjects of ukiyo-e are centered around the floating world around which the style emerged. Among those were portraits of beautiful courtesans (bijin-ga or beauties prints) and popular Kabuki theatre actors (yakusha-e prints). Later on, landscape views serving as travel guides rose to popularity. However, like the very wide audience that enjoyed them, ukiyo-e prints covered all types of topics ranging from scenes of daily life, representations of historical events, still-life depictions of birds and flowers, sumo players competing to political satires and racy erotic prints.

Utamaro And His Beauties

Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1753 – 1806) is renowned for his beauties prints. Prolific and famed during his own lifetime, little is known about Utamaro’s early life. He apprenticed in different workshops and most of his early works that we know of are book illustrations. In fact, Utamaro was closely associated with the famous Edo publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo. In 1781, he officially adopted the name Utamaro that he would use on his artworks. However, it was only in 1791 that Utamaro started focusing on bijin-ga and his beauties prints flourished during this late phase of his career.

His depictions of women are varied, sometimes alone and sometimes in a group, mostly featuring the Yoshiwara pleasure district ladies. His portrayal of courtesans focuses on the face from the bust and up, close to the Western notion of a portrait, which was new in Japanese art. The likeness lay somewhere between realism and conventions, and the artist would use elegant and elongated shapes and lines to illustrate the beauties. We also observe the use of shiny mica pigment for the backgrounds and meticulously delineated elaborate hairdos. Utamaro’s arrest by censors in 1804 for a politically charged work was a big shock for him, and his health quickly deteriorated after that.

Sharaku And His Actors

Toshusai Sharaku (dates unknown) is a mystery. Not only is he one of the most ingenious ukiyo-e masters, but he is also the name we most often associate with the Kabuki actors genre. The exact identity of Sharaku is not known, and Sharaku is unlikely to be the artist’s real name. Some thought he was a Noh actor himself and others thought that Sharaku was a collective of artists working together.

All of his prints were produced during a short span of 10 months between the years 1794 and 1795, presenting a fully mature style. His work is characterized by heightened attention to the actors’ physical traits bordering on caricatural rendering and they are very often caught in a moment of extreme dramatic and expressive tension. Considered somewhat too realistic to be commercially successful at the time of their production, Sharaku’s works were rediscovered during the 19th century, becoming sought after and precious due to its limited availability. Vivid portraits, Sharaku’s works are depictions of lifelike people rather than stereotypes, such as we can see in the Nakamura Nakazo II print.

Hokusai Of Many Talents

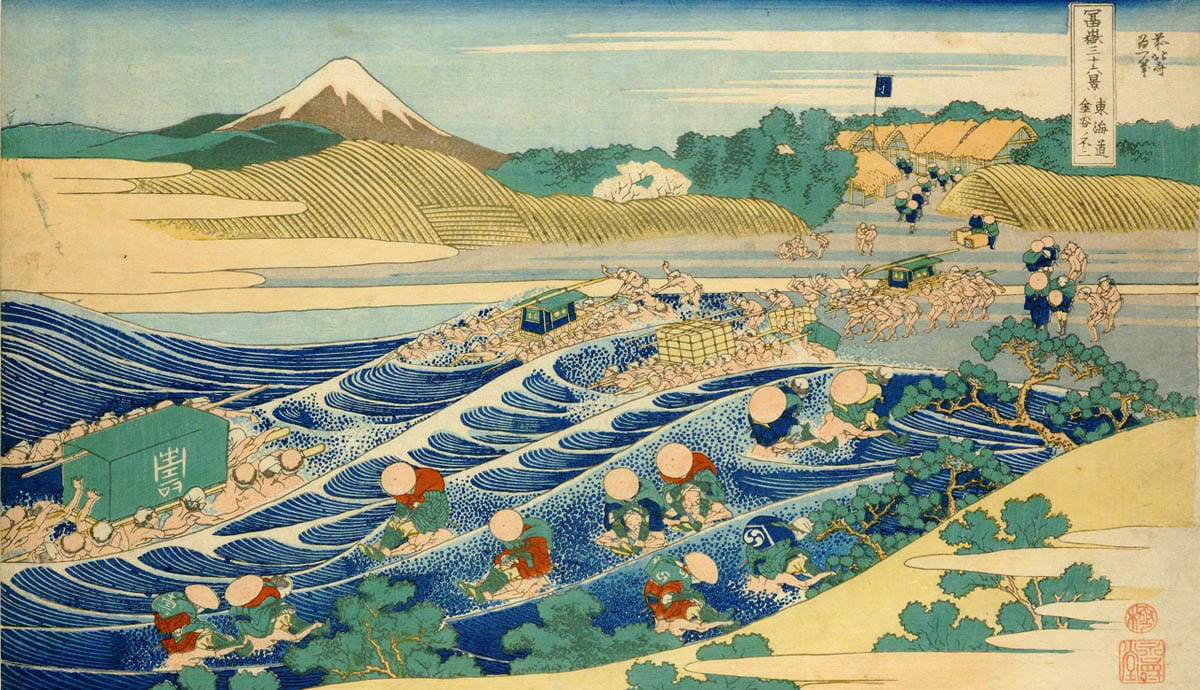

Doubtlessly, Edo-born Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is a household name, even for those of us who are not very familiar with Japanese art. With him, we have in mind the iconic Great Wave off Kanagawa, part of the series of landscapes featured in The Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. However, his creativeness extends far beyond this landmark work. Unlike Utamaro and the mysterious Sharaku before him, he enjoyed a long and successful career. Hokusai is one of at least thirty artist names that the artist used. It is a common practice for Japanese artists to adopt pseudonyms, and most of the time these names are associated with different phases of their career.

Hokusai apprenticed as a wood-carver from an early age at the Katsukawa school and started to produce courtesan and Kabuki actor prints. He was also interested in and influenced by Western art. Gradually, Hokusai’s focus shifted to landscape and daily life scenes that would eventually establish his fame. The majority of his most well-known series were produced in the 1830s, including The Thirty-six Views and others such as One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. They were very much in demand due to the rising numbers of domestic tourists looking for guides to lead them sightseeing at landmarks. In addition, Hokusai was also recognized as an accomplished painter for works on paper and published mangas, collections of sketches, extensively.

Hiroshige And His Landscapes

A contemporary of Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858) was also a native son of the prosperous city of Edo and was born into a samurai class family. Hiroshige himself was a fire warden for a long time. He studied at the Utagawa school of ukiyo-e but also learned how to paint in the Kano and Shijo school styles of painting. Like many ukiyo-e artists of his day, Hiroshige started with portraits of beauties and actors and graduated with a series of scenic landscape views such as Eight Views of Omi, The Fifty-three Stations of Tokaido, Famous Places of Kyoto, and later One Hundred Views of Edo.

Though a prolific artist, producing over 5000 works credited under his name, Hiroshige was never wealthy. However, we do observe from his oeuvre how landscape as a genre becomes fully adapted to the medium of nishiki-e prints. A subject matter once reserved for monumentality on scrolls or screens found its expression in a smaller horizontal or vertical format and its myriad of variations can be seen in series of up to a hundred prints. Hiroshige demonstrates the truly ingenious use of colors and vantage points. His art great influenced Western artists such as the French Impressionists.

Kuniyoshi, His Warriors And More

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) was another artist of the Utagawa school where Hiroshige was also an apprentice. Kuniyoshi’s family was in the silk dying business, and it is possible that his family background influenced and exposed young Kuniyoshi to colors and motifs. Like many other ukiyo-e artists, Kuniyoshi created a number of actor portraits and book illustrations after establishing himself as an independent practitioner, but his career really picked up with the publication in the late 1820s of the One hundred and eight heroes of the popular Suikoden all told, based on a popular Chinese novel Water Margin. He continued to specialize in warrior prints, often set against a dream-like and fantastical backdrop dotted with ghastly monsters and apparitions.

Nevertheless, Kuniyoshi’s mastery is not limited to this genre. He produced a range of other works on flora and fauna as well as travel landscapes, which remain a very popular subject matter. From these works, we note that he was also experimenting both with traditional Chinese and Japanese painting techniques and Western drawing perspective and colors. Kuniyoshi also had a soft spot for felines and made many prints featuring cats during his lifetime. Some of these cats impersonate humans in satirical scenes, a device to circumvent increasing censorship of the late Edo period.