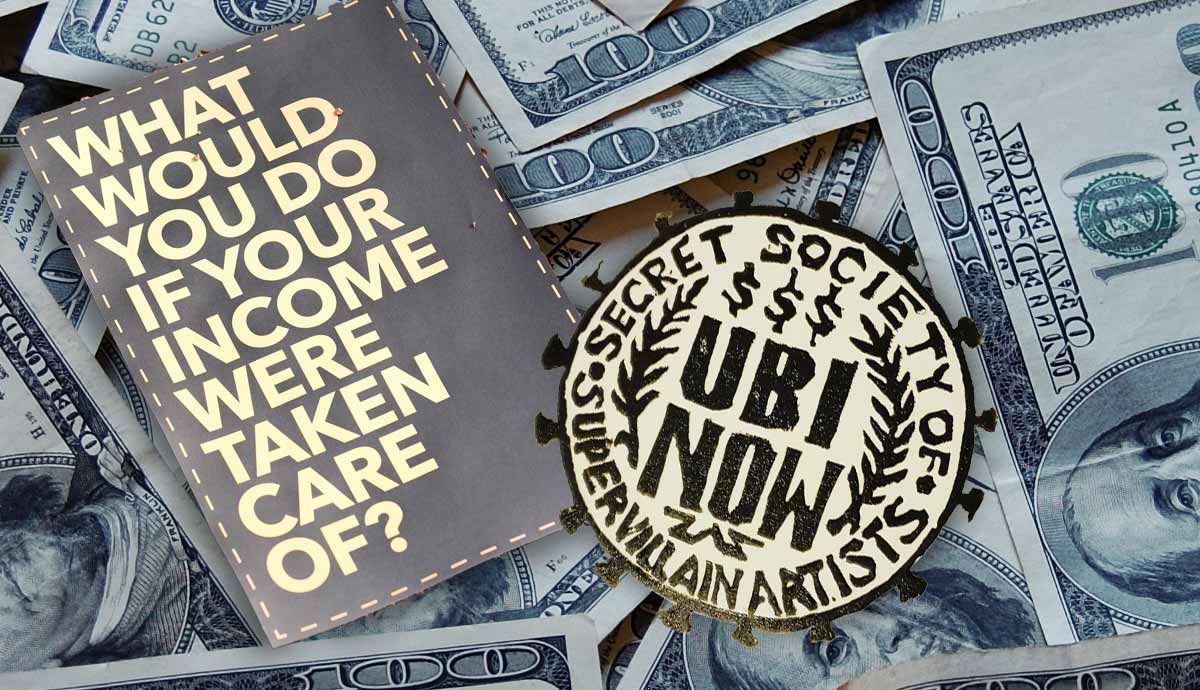

In 2016 Swiss activists from the Swiss Initiative for Unconditional Basic Income staged an eye-catching intervention. They carpeted Plainpalais square in Geneva with a gigantic poster asking a gigantic question: What would you do if your income were taken care of? This is the basic idea behind Universal Basic Income (UBI). In this article, we will take a closer look at UBI, its relationship to modern work and “bullshit jobs”, freedom, and the ways it could be implemented.

Universal Basic Income and Work

Most people in the world spend significant amounts of time doing things they do not truly want to do. In other words, they labor. Now, not all labor is inherently unpleasant. I’m lucky in this respect, I’m a university researcher. When it is particularly cold and wet outside, I can often forgo going to campus and work from home. I also spend the majority of the time at work doing something I enjoy: reading and writing philosophy. Sure, sometimes things are a drag, but that’s part of working for a living.

Many other people are not so well placed. Some forms of labor we rely on for our standard of living are deeply unpleasant. Many of us wear clothes that are produced in sweatshops, use mobile phones which contain rare earth minerals mined under life-threatening conditions, and our online purchases are delivered by an army of overworked and under-paid subcontracted drivers.

Bullshit Jobs

However, even jobs which are better, in the grand scheme of things, have their discontents. In his book Bullshit Jobs the late David Graeber argues that many people’s jobs in contemporary Western societies are bullshit – that is, jobs that are primarily or entirely made up of tasks that the person doing that job considers to be pointless or unnecessary. For example: paper-pushing jobs like PR consulting, administrative and clerical tasks created by subcontracting public services, telemarketing, and financial strategizing.

The tasks that make these jobs up are meaningless and unnecessary. If these jobs ceased to exist, it would make little difference to the world. Not only that, but the people who do these jobs know this themselves.

Not all jobs are bullshit. Even if we could somehow eliminate all the bullshit jobs in the world, there would still be lots of jobs that clearly need to be done. If we want to eat, someone has to grow food. If we want shelter, someone has to build it. If we want energy, someone needs to generate it. Even if we managed to get rid of all bullshit jobs, there would still be boring, difficult, dirty, tiring jobs that really do need to be done.

Perhaps a basic and inevitable feature of our social contract is that most people are not doing what they want to do with their time. People need to earn a living; other people need things done. In western, industrialized market economies, those with things that need to be done employ those who need to make a living. What Adam Smith called ‘our innate propensity to truck, barter, and exchange’ leads to us creating a market economy centered around jobs.

Yet, what if this pattern isn’t inevitable? What if we didn’t need to spend our time doing jobs in exchange for income? What if our income were taken care of? Although it sounds utopian, this is the possibility that a Universal Basic Income (UBI) presents us with.

But what is UBI? In a nutshell, it is a grant paid to every citizen, irrespective of whether they work, or what their socioeconomic or marital situation is. UBI has a few distinctive features: it is generally paid in cash (as opposed to vouchers or direct provision of goods), it is paid in regular installments, it is the same amount for everyone, and it is not paid on condition that people be willing to work.

Universal Basic Income and Real Freedom

In his book Real Freedom for All: What (If Anything) Justifies Capitalism?, Philipp Van Parijs argues that a Universal Basic Income offers the possibility of ‘real freedom for all’. Being free in the real sense isn’t simply about things not being prohibited. Although freedom is incompatible with totalitarian prohibitions, it requires more than this. Just because it isn’t illegal to write a book doesn’t mean I am really free to write a book. For me to be really free to write a book, I must have the ability to write a book.

Having the ability means I will need the mental ability to think and use language to make sentences, the money for materials (paper, pens, or a laptop), the physical ability to write, type, or dictate, and the time to think about the ideas in the book and put them down on paper. If I’m lacking any of these things, there is a sense in which I’m not really free to write a book. By providing us with a steady stream of cash, a UBI would help increase our real freedom to do the things we want to do; be that writing books, hiking, dancing, or any other activity.

How much freedom a UBI can give us will depend on how much cash each person gets from their UBI. Different advocates of UBI argue for UBIs of different sizes, but a popular view is that a UBI would provide a modest, guaranteed minimum income, sufficient to meet basic needs. How much would this be in real money? For our purposes, let’s say that we are considering a Universal Basic Income of 600 GBP, roughly the amount paid out in the Finnish UBI pilot which ran between 2017 and 2018. But this does all depend on where the UBI is being proposed, as the cost of meeting needs is higher in some places than in others.

Would a Universal Basic Income Change Your Life?

To return to the question with which we started this article, what would you do if you were guaranteed 600 GBP a month? Would you cease to work? Would you work less? Would you retrain? Change jobs? Start a business? Leave the city for a simpler life in a remote part of the countryside? Or would you use the extra income to move into the city?

For what it’s worth, here is my answer. I’d aim to continue to do the work I currently do. I’d continue to apply for the fixed term research contracts that early career academics like me are employed on. I’d continue to try and secure a permanent academic job lecturing in philosophy. That isn’t to say that nothing would change for me. The extra 600 GBP a month would provide an enormous boost to my financial security. It would enable me to save up money for future lean periods of un- or under-employment. In my more reflective moments, I’m a cautious type. The more likely result is that, despite my best intentions, I’d find it hard to save it all. I’d probably increase my spending a bit too: go out for dinner, buy another guitar, inevitably spend a chunk of it on books.

‘Sure’, an opponent of UBI might say, ‘some people would continue to work, but lots of people hate their jobs. They’d likely cut down their hours or cease working altogether. People need incentives to make them work. With a guaranteed unconditional income, wouldn’t we be faced with mass resignations?’

Universal Basic Income Experiments

Ultimately, this is a difficult question which can’t be answered from the philosophers’ proverbial armchair. It can only be answered by testing the hypothesis empirically. Thankfully, there have been a number of trials of Universal Basic Income around the world, and some of the results are in.

Unfortunately, the evidence isn’t completely clear cut, as is often the case with complicated matters of public policy. In Iran, where the government instituted direct payments to all citizens in 2011, economists have found no appreciable impact on work participation. The Alaska permanent dividend fund, which pays out a portion of the state’s oil revenues to individuals as cash, also has no effect on employment. However, experiments conducted in the USA between 1968 and 1974 did have a moderate effect on the amount of labor market participation.

Studies on the effects of a UBI on the labor market are still ongoing. Pilots aimed at studying the effects of making the Universal Basic Income conditional on working are currently ongoing in Spain and the Netherlands.

Working Less

At this point one might ask: even if a UBI did affect labor market participation, is it really that bad if we work less? Lots of the jobs in society aren’t just bullshit, many of our industries are downright harmful for the environment. With less of an incentive to work and produce as much, we might stand a better chance of not overheating the planet. More free time could also enable people to spend more time doing things which are beneficial to all of us, but unpaid. Think community gardening, meals-on-wheels, volunteering in food-kitchens, setting up community fetes and initiatives, or volunteering to coach a kid’s football team. In his book The Refusal of Work, sociologist David Frayne found that many people who had opted to spend less time doing paid labor did just that: they spent more time doing productive, but unpaid, work.

Whilst this may be true, not everyone is necessarily that community minded. For every person that uses their extra free time to engage in valuable, but unpaid, labor; there will be more than one who will spend their extra time in pursuits that benefit only themselves, for example idling the time away strumming a guitar or surfing on Malibu beach. Why should they get the same amount of UBI as those who spend their extra free time running a food bank? Isn’t that unfair on those who are contributing to society? Aren’t the idle taking advantage or exploiting those who work?

Unfortunately there isn’t much a defender of a UBI can do to convince anyone who can’t shake off this concern. The unconditionality of a UBI is one of its central distinguishing features, the main reason why a UBI would enhance freedom. Giving up on it, thus, is to give up on the idea of ensuring real freedom for all.

Universal Basic Income vs. Participation Income

It is concerns like these that have led the late economist Anthony Barry Atkinson to argue for the idea of a participation income as an alternative to a UBI. On a participation income, people’s income would be conditional on contributing to the economic and social activity of the country. By introducing this condition, a participation income isn’t vulnerable to the objection that it is unfair on those who work or do other socially valuable activities. This, Atkinson suggests, makes the participation income much more politically feasible. It would also allow us to secure some, but not all, of the benefits of a UBI. A participation income would provide people economic security, and might enable people to spend less time in paid employment in the labor market (so long as they spend some of their time contributing to socially valuable activities).

What it can’t get us, however, is the open-ended freedom to do as we will. If, like me, you think freedom is valuable, this demand for real freedom for all isn’t something we should give up on. What we need to do is make a better case for why being free is important to all of us, in the hopes of convincing those who are worried about people doing nothing.