What were a contingent of Danish, English, and Russian Vikings doing guarding the Byzantine Emperor at the height of the Viking Age? The Varangian Guard was a most modern phenomenon; an international mercenary group, assembled from the world’s most terrifying warriors, who faithfully guarded the Emperor for almost five centuries. To get to grips with their history, we have to paddle down the inland waterways of Eastern Europe, trudge through the sands of the Levant, and climb the mountains of Byzantine Italy.

The Varangians of the Varangian Guard

Before we can talk about who the Varangian Guard were, we have to discuss what a “Varangian” is. No, not that Star Trek race (that’s the Ferengi). Rather than being a specific people who thought of themselves as “Varangians”, the term broadly refers to the name that people in Eastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean attached to those of Norse (Scandinavian) origin.

The modern Anglicization of “Varangian” is derived from a number of different Medieval words, such as the Medieval Greek Βάραγγος, “Várangos”, and the Old East Slavic Варягъ, “Varjagŭ”, both of which refer to Norse people. They are loan-words that were transliterated from the Old Norse word væringi, meaning “sworn companion”. Scholars have taken this to mean that the Norse people that were regularly encountered in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean were either mercenaries or vassals who were sworn into the service of local feudal elites. Thus, when historians and histories talk of “Varangians” they are talking about the same people we usually know as “the Vikings”: the Norse raiders, traders, settlers, and mercenaries who spread explosively out of Scandinavia from the 9th century CE.

The Vikings in the East

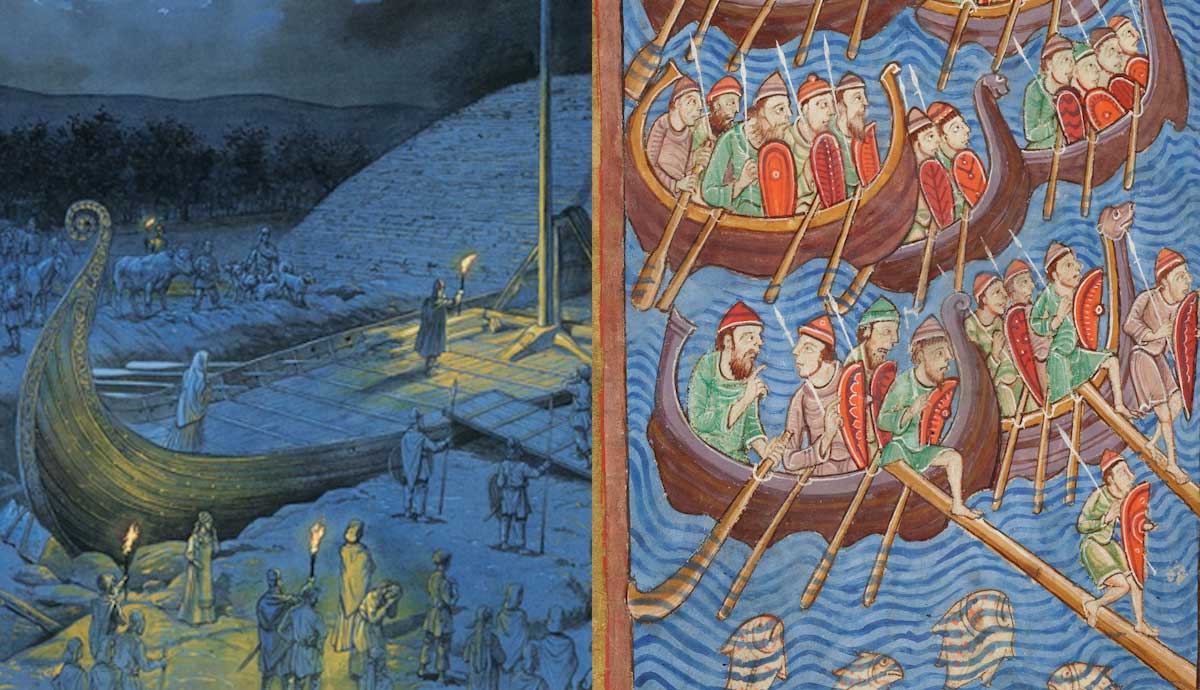

Commonly, we associate the Vikings with Northern and Western Europe. Obviously, the Norse peoples originated from Scandinavia — predominantly modern Denmark, Norway, and Sweden — before they began raiding and colonizing England, Iceland, and Normandy (modern northern France). But at the same time, the Vikings also headed east. Viking expeditions traveled down the many waterways of the eastern Baltic Sea, into modern Eastern Europe and Russia. There, they found an alternative trade route to Central Asia, India, and China, known as the “Volga trade route”.

Instead of threading through Asia Minor and into the Mediterranean via Constantinople, the Volga trade routes headed up from the Black Sea straight across the belly of Ukraine and Russia on large navigable rivers like the Volga and the Dnieper, into the Baltic near the ancient city of Novgorod. By the middle of the 9th century, the Vikings had formed their own state along this route in tandem with local Slavic, Finnic, and Baltic tribes, known collectively as the Kievan Rus’. In traditional histories, the Viking king Rurik (hailing from Roslagen in eastern Sweden) founded the Kievan Rus’ state sometime in the 9th century, before moving his headquarters to Novgorod, in modern-day Russia.

The Heritage of the Rus

Debate rages as to whether the Volga trade routes were already established under the control of local Slavic peoples, or whether it was the Vikings themselves who first forged these routes. The 9th century Rus’ people are identified in early texts (including the 12th century Rus’ Primary Chronicle) specifically as Varangians, Vikings who lived in what is now Sweden, and who had migrated down the River Volga — but there is more than a little doubt about this. Arab writers who made contact with these traders at the southern-most part of the Volga trade routes describe the Rus’ as Turkic, which would place their origins in the Central Asian steppes much further east.

Linguists, however, consider the word ‘Rus’ an imported word from the Finnic for “Sweden” — “Ruotsi”. This word itself is likely related to the Old Norse róþsmenn, meaning “rowers”, referring to the means by which the Vikings traversed the inland rivers of the region — or to Roslagen, the Swedish home of King Rurik. But the paucity of early sources, and the understandable desire to give agency to the specific history of Slavic peoples, has left much uncertainty.

Regardless, it is certainly an incontrovertible fact that people with a strong Norse cultural heritage (both Scandinavians and the Eastern European Rus’) were trading with, acting as mercenaries for, and accepting vassalage in, Eastern Mediterranean states from the earliest part of the Viking Age.

The Genesis of the Varangian Guard

Most historians trace the origins of the Varangian Guard to a treaty between Byzantine Emperor Basil I, and the Varangians of the Kievan Rus’. The Byzantine Empire was easily the wealthiest and most organized state in the region, especially compared to the fragmented and economically backward Western European states. The Varangians, who retained every bit of the ferocity of their Scandinavian cousins, looked at Miklagard (“the City of St. Michael” — Constantinople) as a tempting target for raids. Crossing vast distances on the wide rivers of Eastern Europe (and rolling their flat-bottomed boats on logs overland), they launched attacks on Byzantine settlements around the Black Sea and Asia minor from the mid-9th century. These terrifying warriors would have worn what we think of as Viking garb: inhuman eye-mask helmets, bright chainmail, and garishly painted round shields.

The Rus and New Rome

In 860 CE, these people dared to attack Constantinopolis itself, laying waste to the countryside and ransacking churches. The Patriarch Photios, whose writings have come down to us, writes of “a dreadful bolt fallen on us out of the farthest North” and a “thick sudden hail-storm of barbarians burst forth”. This depiction of the Varangians as a force of nature really does underline the apocalyptic fury the Byzantines witnessed.

The response of the Byzantines was a fascinating one — rather than reacting in kind with a punitive expedition, they responded in a restrained Roman fashion, seeing an opportunity to make these violent pagans into a valuable asset. Instead of soldiers, they sent missionaries. Clearly, these Byzantine missionaries were able to persuade the elites of the Rus’ that cooperation was more profitable than war, and by the end of the 860s the Rus’ had begun to convert to Christianity and ally themselves with the Byzantines.

In the early 10th century CE, Emperor Leo IV and Rus’ King Oleg signed a formal treaty, known as the Roman-Rus’ Treaty of 911. This document reads as if it were merely setting down in writing what must have been a long-standing alliance, and it gives us a valuable insight into Byzantine-Rus’ relations. It speaks of obligations that the Rus’ had to aid Byzantine ships and to pilot them down their rivers. But most importantly of all, it cemented the military relationship between the Rus’ and New Rome. The treaty provided that the Rus’ could now serve at will in the Byzantine military forces. This was doubtless an excellent source of prestige and loot for the Varangians, as well as a serious military boon for the Byzantine Emperor. Seven hundred Rus’ warriors participated in Emperor Leo’s invasion of Crete, in the same year as the treaty, and five hundred were sent by the Rus’ on a second expedition in 949. The use of foreign mercenaries was rare in the Byzantine military in that period, and so we can be sure that the Rus’ were trailblazers.

The Varangians Get Political

Whilst in the 10th century Rus’ mercenaries held a narrow military role, summoned as levied mercenaries to serve as shock-troops in the Emperor’s army, the revolt of Bardas Phokas in the late 980s marked a sea-change. They made the transition from being battlefield troops to being a political bodyguard — the real Varangian Guard.

Byzantine politics was legendary for fulfilling every stereotype of court intrigue. Backroom deals, backstabbings (sometimes literal ones), and poisonings litter the pages of Byzantine history, with few Emperors managing to rule for more than a few years. As the Rus’ princes began to gravitate towards imperial politics through their rising wealth and smart marriages, it was inevitable that through their significant military might they became embroiled in court intrigue.

In 986, the newly-crowned Emperor Basil II sought to weaken the influence of his court rivals, the House of Phokades-Lekapenos, by stripping them of various court positions. Joining with external enemies in a tale worthy of an opera, the scion of the House Bardas Phokas rose in rebellion against Basil. However, Basil had a final card to play, and as usual, it was a woman who was the butt of the situation. Basil married his sister Anna off to the Rus’ prince Vladimir the Great in exchange for military assistance, which Vladimir duly provided in the form of a massive army of 6,000 wailing Varangians. These troops were critical in putting down the rebellion, and this event placed Varangian military power squarely behind the imperial throne and marked the foundation of the Varangian Guard.

The Emperor’s Guard

From the start of the 11th century, there was a permanent brigade of Varangians in the personal employ of the Emperor: the Varangian Guard. It is in this period that the word “Varangian” appears, referring to the group’s bonded status to the Emperor. In documents from this time, the word seems to have been used specifically to refer to the Norse Viking-descended inhabitants of the Rus’, as distinct from the Slavs (before this period, they were likely all seen as Rus’). The Varangian Guard itself was likely formed from the Rus’ whom Prince Vladimir the Great of the Kievan Rus’ led on his joint campaigns with Emperor Basil II in the Levant and North Africa.

The concept of an “imperial guard” was an ancient one, with the notorious Praetorian Guard guarding (and later dominating) the Emperors of the Western Roman Empire — but this tradition had died out many centuries earlier. While the imperial Byzantine army was riven with rivalries and political splits, the Varangian Guard would be fanatically loyal to the person of the Emperor, and they would be both a devastating battlefield asset, and an insurance policy against intrigues at home.

The Varangian’s alien dress and fearsome demeanor would become a symbol of the Emperor’s presence. Modern archaeology has revealed the path of the Varangian Guard around the Mediterranean world, with 11th-century Norse equipment being found in Syria and Bulgaria, both dominated by Basil II in this period.

The Battle of Cannae (No, the Other One)

A special mention must be made of the Battle of Cannae, which took place in 1018 CE on the same field where Hannibal put the Roman Republic’s Legions to flight in 216 BCE. The Varangian Guard were sent to Byzantine Italy to help the Catapan Basil Boioannes stave off a rebellion of the local Lombards. The Lombard nobles had hired some Norman mercenaries, Norse-descended adventurers from northern France, to smash the Byzantine occupation. Thus, two groups of Norseman faced each other across the battlefield: Norman heavy cavalrymen and the Varangian Guard. Though Byzantine Italy’s days were numbered, the Varangian Guard had the better of it that day, massacring the Lombards and killing the leader of the Normans, along with most of their contingent.

The Changing Face of the Varangian Guard

The Varangian Guard became a permanent fixture of the imperial court after the death of Basil II in 1032, and they gradually began to change. The Byzantines’ extremely positive experience of foreign mercenaries (begun by the Rus’) meant that more and more federated troops began to serve in the imperial armies, and the Varangian Guard started to attract Norse warriors from even more distant lands.

A young Danish nobleman called Harald Hardrada, future King of Norway, served in the Varangian Guard as a young man, eventually becoming its commanding officer. “Araltes” (Harald) was hailed in contemporary Byzantine texts as a prodigious warrior. These Northern European warriors were commemorated in a set of carvings in Sweden known as the “Varangian Runestones”, which describe great voyages to the East, by those serving in the courts of foreign kings. These men frequently returned home with exotic goods and many tales.

Anglo-Saxons from modern-day England are also recorded as having been in the Varangian Guard, toward the end of the 11th century. In 1081 CE, Anglo-Saxons and Normans faced each other — not at Hastings, but in Dyrrhachium, in modern-day Albania, with the majority-Anglo-Saxon Varangian Guard facing off against the naturalized Italo-Normans of southern Italy. Anglo-Saxon noblemen even formed a short-lived Balkan colony at the Varangian Guard’s Black Sea strongholds after their exile from England in 1066, called “Nova Anglia”. Clearly, the Varangian Guard was but a small part of an enormous cross-cultural exchange that took place between Northern Europe and the East towards the end of the Viking Age.

The End of the Varangian Guard

In all, the Varangian Guard likely served the Emperors of Byzantium for around five centuries. They were present at the ignominious sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, fighting to defend the city from the Crusaders. The last references we have to the Varangian Guard are from as recently as the 15th century. Although their function became mostly ceremonial after the exile of the Emperor by the Crusaders and the subsequent decline of the Byzantine Empire. The deep links between Northern European families and the Byzantine state remained, however, with bonded English warriors present at the defense of Constantinople against the Turks in 1402.

The Varangian Guard were not just one of the most fearsome guard units in military history — they were also a nexus of East and West, a point at which martial and political cultures collided and synthesized to create new forms. Spanning Rus’, Scandinavia, England, and the Mediterranean, the Varangian Guard perfectly illustrate how the medieval world was rapidly shrinking and hurtling toward modernity.