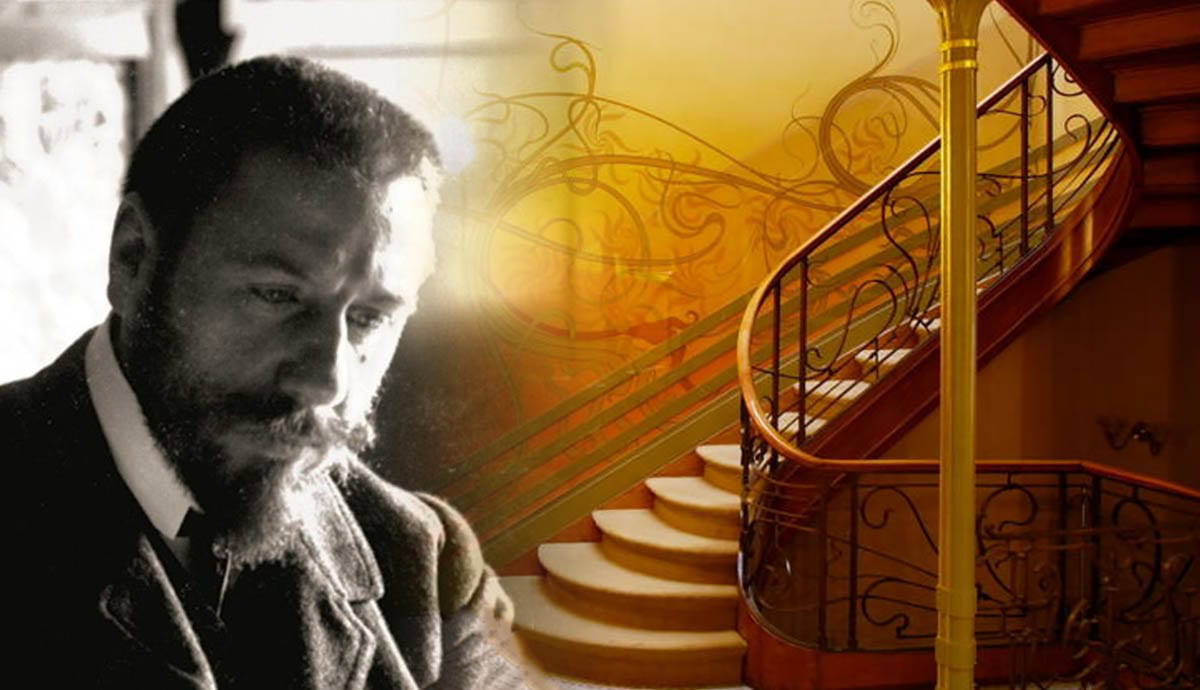

Victor Horta was a famous Belgian architect and he was considered the Father of Art Nouveau. However, the public did not always acknowledge his genius. Born in Ghent in 1861, Horta had a creative mind and proceeded by trial and error before finding his pathway. Victor Horta’s fame came with his first Art Nouveau architectural masterpieces at the turn of the 20th century. Yet, as the Art Nouveau movement quickly became outdated, the end of his career was a difficult period, and Horta died in almost complete indifference. Discover how several events and encounters determined his career and life.

8. Victor Horta Met New Clients After Becoming A Freemason

Aged 27, Victor Horta joined a Masonic lodge, a booster for his starting career. In 1888, Horta joined Les Amis Philanthropes, the “Philanthropic Friends”, a Masonic lodge of the Grand Orient of Belgium. It meant a real opportunity for him as he met potential future clients.

First, Eugene Autrique, a famous Belgian engineer, chose Horta to build his private house. Despite the restricted budget and following mostly traditional shapes, Victor Horta managed to add new decorative elements.

His first real Art Nouveau style work comes from order from his fellow mason, Emile Tassel. Finished in 1893, the Hotel Tassel, a private mansion, represents the first worldwide example of Art Nouveau in architecture.

Just like Arts and Crafts artists did a few years earlier in Britain, Horta used new building materials such as iron and glass. Yet, he was the first architect to use these materials in a private house. Horta did not take his inspiration from ancient styles but studied and used nature as an example to create new modern decorative elements never seen before. He was one of the first architects to use the “ligne coup de fouet” or “whiplash line” in his Hotel Tassel. Inspired by flower stems, a whiplash line is a dynamic and sinuous line, which ends with an “S” shape. He used the whiplash in the ironwork, and for many decorative elements, even furniture pieces and door handles. Victor Horta conceived his architectural projects as ensembles, designing the whole building as well as the tiniest of decorative details, a total art. His work inspired many other Art Nouveau artists such as Hector Guimard and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy.

7. “The Laggard,” Horta’s Undeserved Nickname

The Maison du Peuple, literally The House of the People, is considered as Horta’s masterpiece. In 1895, the leaders of the Belgian Workers’ Party (Parti Ouvrier Belge/Belgische Werkliedenpartij) commissioned Horta to build their new headquarters. The party was looking for an architect capable of novelty, no longer using the codes of the clergy and the bourgeoisie. In his memoirs, Horta claimed not to be political. Yet, he was friends with some of the party’s leaders, such as Emile Vandervelde. Like other socialist rulers, both belonged to the masonic lodge “Les Amis Philanthropes.”

While designing the Maison du Peuple, Horta earned the Flemish nickname “den stillekens aan,” meaning the laggard. The design of the building took him four years. The nickname does not do Horta justice as he was a real perfectionist and used to work even on the smallest details. He needed six months to complete preliminary plans. It took fifteen men and one and a half years to duplicate those plans in real size. They needed 75 rolls of paper to do so, or 8437.50 square meters of paper, representing more or less the equivalent of the surface of Brussels Grand Place. Horta supervised and corrected all the plans personally.

In 1899, the finished building was not only Horta’s masterpiece but also a chef-d’oeuvre of modernism. The monument built in red brick, white cast iron and glass offered large rooms filled with natural light. Horta achieved to build his masterpiece on a narrow and steep plot. The multifunctional building included a restaurant and several shops, as well as a clinic, a library, offices, meeting rooms, and a large 2000-seat auditorium. This building represents a milestone in the evolution of Horta’s work; the façade had fewer visible Art Nouveau decorative elements. Though still present, he progressively abandoned the curves and vegetal-inspired decorative elements for sober lines showing off the modern materials. The Maison du Peuple was the Workers’ Party landmark. It brought art, space, and light to workers, two elements missing from their homes.

6. Horta’s Art Nouveau Masterpiece, Victim Of “Brusselization”

Sadly, The Maison du Peuple, Horta’s masterpiece, was demolished in 1965. This building that brought so much joy and pride to its designer as well as to the entire Workers Party soon became too small for their needs. After the end of WWII and the transformation leading to the creation of the Belgian Socialist Party, they abandoned the building.

Today, Victor Horta and the Art Nouveau movement are renowned internationally. However, it has not always been the case. At the beginning of his career, the public appreciated Horta’s innovative work. Yet, because of the decorative excess of certain artists, Art Nouveau quickly became outdated. The refined designs of Art Deco and Modernism became the new trend.

Today used as a generic urbanization term, “Brusselization” takes its origin in the 1960s-Brussels. Careless contractors demolished several historical monuments to replace them with soulless concrete office towers. Brusselization is used to describe poor urban planning, designed in a building-fury notwithstanding with neighborhood’s harmony. Horta’s Maison du Peuple was one of the best-known victims of this process.

During the 1960s, few were the personalities ready to defend Horta’s work. Art Nouveau, or “le style Nouille” (Noodle style) as many detractors called it, was well outdated. Victor Horta himself anticipated the potential destruction of several of his buildings. When the Maison du Peuple’s destruction was scheduled in 1965, many international personalities spoke out. Several hundred people signed a worldwide petition. Among them were numerous architects such as Mies van der Rohe, Jean Prouvé, I. M. Pei, Walter Gropius, Alvar Aalto, and Gio Ponti. Despite their objection, the demolition happened as planned. The Blaton Tower, a 26-story skyscraper, soon replaced the building.

A subway station in Brussels (Horta) and Horta Grand Café in Antwerp still exhibit some elements of the late Maison du Peuple. A recent collaboration between the Horta Museum and the College of Architecture La Cambre-Horta, part of the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB), virtually rebuilt Horta’s masterpiece. In the Horta Museum, a 3D movie of the Maison du Peuple is projected.

5. Forced Into Exile: A Considerable Change In Style

In 1916, Victor Horta traveled to London to assist the Town Planning Conference organized by the International Garden Cities and Town Planning Association. This event focused specifically on how to reconstruct Belgium once WWI came to an end. The entire country suffered terrible destruction, and whole neighborhoods needed rebuilding.

While in London, German authorities found out about his presence, and Horta was forced to leave the United Kingdom. He could not return to Belgium, so he set out for the United States. As a former Professor at the Free University of Brussels (ULB), Victor Horta gave lectures at several local universities, even the most prestigious, such as George Washington, Harvard, MIT, and Yale. The American skyscrapers and modern buildings strongly influenced the Belgian architect. Horta realized that Art Nouveau was not designed to last; he had to adapt his style. He already operated some changes in the Maison du Peuple project. His exile confirmed his work’s new direction towards the simpler lines of Art Deco and Modernism. His exile in the United States lasted until 1919, after the end of the war.

Horta’s later works further display these stylistic changes. The Centre for Fine Arts (1923-1929) and Brussels’ Central Station which opened in 1952, five years after his death, represent perfect examples of his new style.

4. A Great Architect And A Passionate Collector

In the 19th-century, westerners were fascinated by Asian traditional art. The opening of Japan’s borders to foreigners around 1860 further amplified the interest in this Far Eastern culture. Over the years, Horta collected a large variety of Asian art pieces and objects. Unfortunately, his collection was sold at auction. The Horta Museum, which occupies his former home, managed to acquire some of his old collections.

Art Nouveau captures its inspiration in the flowing figures of natural elements. The movement also takes Asian art as an example, especially Japanese art. Japanese artists depicted simple decorative elements inspired by fauna and flora. Even if it was quite an expense for him, Horta bought a subscription to “Le Japon artistique” (Artistic Japan), a journal edited by Siegfried Bing.

Another collection of Horta, a more peculiar one, is his lot of marble samples. His widow, Julia Carlsson, donated this lot to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.

3. Baron Horta Received The Honors Belatedly

Although Victor Horta’s later works were not as successful as at the beginning of this career, he received great honors. He acquired several high honorific titles such as Officer of the Order of the Crown, and Officer of the Order of Leopold. In 1932, King Albert I of Belgium granted him the title of Baron.

Along with other personalities of the Belgian history, a portrait of Victor Horta appeared in the last series before the Euro of the 2,000 Belgian Francs note.

2. Horta’s Mémoires, A Guide To Understanding His Work

Few of Victor Horta’s own designs and plans remain today as he never published his work. At the end of his career, he even burned most of his papers. Yet, in 1939, he started to write his “Mémoires.” Only published in 1985, this volume offers a glance into the architect’s mind. He gives a comprehensive description of his thoughts while designing his masterpieces.

1. Would You Like To Purchase One Of Victor Horta’s Masterpieces?

Yes, it is possible. Victor Horta’s properties can be eventually purchased as one appears from time to time on the market. At the time of writing, one of them is for sale in central Brussels. This property is an extension of the prestigious Hotel van Eetvelde. Edmond van Eetvelde, the administrator of Congo Free State, commissioned Horta to build his private house in 1895. In his memoirs, Horta recalls the freedom he was granted by van Eetvelde to create something new and audacious.

The property currently for sale is the first extension, which Horta designed in 1899 upon request of van Eetvelde. Despite some architectural changes made during the 1950s to transform the mansion into offices, it still maintains Art Nouveau features restored in 1988. Architect Jean Delhaye, collaborator and since the end of the 1950’s advocate of Horta’s work, settled his office in the extension. Since 2000, UNESCO has listed Hotel van Eetveld among its World Heritage sites.