Egyptomania, the fascination with all things ancient Egyptian, gradually took possession of Victorian Britons’ minds. The Napoleonic campaigns in Egypt between 1798 and 1801 had started a process whereby its treasures were studied and exported to Europe. Museums across the continent were filled with archeological remains freshly excavated from the desert. With the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone in the early part of the century, the understanding of ancient Egypt grew exponentially. As a result of the ability to read ancient manuscripts and the decorations covering Egyptian monuments, the foundations of Egyptology as a science were laid. By the century’s end, the design features and styles of historical Egypt had become a visible part of Victorian art, public and domestic life, and popular literature.

Revealed Secrets Ignite Egyptomania: A Growing Obsession With Ancient Egypt

With increased travel to the country, resulting in numerous written accounts of its history and geography, the Victorian imagination was ignited by new ideas of the past and fresh, unexplored destinations for the present. The craze for Egyptian objects sparked innovation in design, incorporating elements from the country’s ancient buildings and parchments.

Writers and artists made their way to Egypt, eager to discover and depict all that Egypt offered in journals, books, and paintings. For the rest of the century, Egyptian history and the stylistic features found in its artifacts influenced many parts of British culture in art, architecture, and literature.

Back home, exhibitions featured displays designed to evoke Egypt of the past. A new awareness of the fate of the Egyptian dynasties made Victorians ask questions related to their own empire. Worries about imperial decline, already a subject of extensive writings, caused Victorian Britons to regard Egyptian history as an exemplar and warning of their potential future. Ancient Egypt was a source of inspiration but also a warning from the past. Egyptomania became more than just a cultural phenomenon. It reflected the worries and doubts of Victorian Britain.

Egypt: A Source of the Sublime

Artists like John Martin (1789-1854) produced grand works which portrayed Biblical history in an apocalyptic light. In paintings like Seventh Plague of Egypt (1823), Martin drew on illustrations of Egyptian monuments to depict a Biblical scene, showing Moses calling down a plague upon Egyptians and the pharaoh. This work was an attempt to use Egypt to display the emotion and drama of the Biblical narratives. It, and many similar works, sought to supplement the Bible stories, strengthening faith. Influenced by Turner and the Romantic poets, Martin specialized in paintings that evoked the Sublime. This movement, dating back to the eighteenth century, sought to provoke a powerful emotional response in the viewer by depicting images of power, terror, and vastness. In Egyptomania, Martin found a rich and new vein of the Sublime by combining it with images from Biblical Egyptian history. Prints of the Seventh Plague of Egypt were widely circulated and became very well known.

Imagining Egypt’s Reality

Other artists used different strategies to show Egypt to Victorians. Less influenced by Romanticism, Scottish artist David Roberts (1796-1864) traveled to Egypt in 1838 and, from that journey, produced works that were collected in an illustrated book that became celebrated in Mid-Victorian Britain. His book, Sketches in Egypt and Nubia (1846-1849), from which lithographs were produced, delighted Queen Victoria. While John Martin focused on the emotional power of history, Roberts showed the detail of historical Egyptian sites, such as the pyramids.

Victorian visitors would have found Roberts’ portrayals of the ancient sites accurate. His work is meticulous, detailed, and realistic. This was Egyptomania and history joined together as a travelogue. Roberts’ work produced a sense of Egypt’s reality, encouraging travel pioneer Thomas Cook in his efforts to create tourism for the growing number of Victorians willing to make the journey.

Egyptomania Finds Its Home In Victorian London

By mid-century, Egyptomania had secured a place in the Victorian imagination, allowing it to be included in The Great Exhibition of the Works of All Nations, which was the creation of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert. Housed inside an innovative and spectacular glass construction in the heart of London, it was a showcase of design, technology, and culture, bringing all the nations of the world together under one roof.

Among a bewildering variety of over 100,000 other displays, visitors could gaze in wonder upon giant statues showing the Egyptian pharaoh, Rameses II. These were copies of two figures at the entrance to the temple at Abu Simbel in Egypt. Later, when the exhibition building was moved to another London location, Owen Jones, its Joint Director of Decoration and an influential design specialist, created an elaborate Egyptian Court, complete with standing figures copied from originals.

Dressing With Egyptomania In Mind

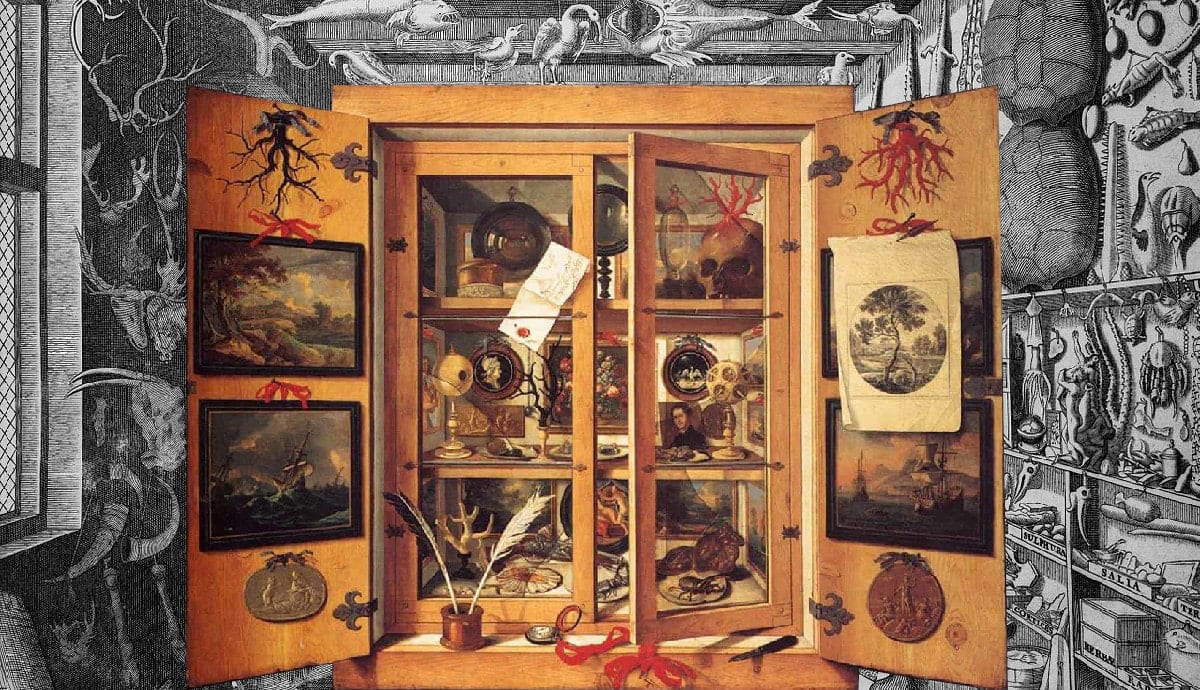

As the century progressed, treasures from Egypt flooded into London and all parts of Britain. The British Museum gradually expanded its collection of artifacts, drawing crowds of visitors. Wealthy individuals accumulated collections of original items taken from finds in the Egyptian desert. The uniqueness and beauty of ancient Egyptian relics created a demand for copies.

This trend influenced tastes in jewelry. Soon, makers of decorative pieces were producing ornate and delicate items for their most discerning clients. The scarab beetle was an ancient symbol of rebirth to Egyptians. The sacred insect was often incorporated into jewelry pieces in the form of rings or amulets. As with tastes in Egyptian-influenced pictorial art, beneath the surface appeal of these often beautiful objects lay a suggestion of the continuing Victorian fascination and obsession with mortality.

In everyday life, Victorian gentlemen wore coats whose buttons were designed like pharaoh’s heads. They smoked Egyptian cigarettes and kept them in cases decorated with images from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Not to be outdone, women wore brooches showing scarab beetles and charms designed in the shape of sarcophagi. Egyptomania had become the height of fashion for the discerning Victorian.

Egypt Furnishes the Victorian Home

Egyptian motifs and designs became visible in many aspects of daily life. Furnishings incorporated Egyptian-style features in order to satisfy an ever-growing demand. An example is the Thebes Stool, designed in the 1880s. It shows the influence of imported furnishings, which designers like Christopher Dresser (1834-1904) would have seen on visits to the large and growing collections at the British Museum and the South Kensington Museum in London.

Through the creative choices of designers, Egyptomania was shaping the domestic lives of affluent Victorians. In 1856, architect and designer Owen Jones published an influential collection of designs in his book, The Grammar of Ornament. Included in this volume were a variety of Egyptian design patterns and motifs which found their way into wallpaper design in Victorian households. Jones created a design language used with textiles, furniture, and interiors. Many of his students went on to shape the use of Egyptian ideas in everyday Victorian objects.

Public Spaces Shaped by Egyptian Style

Victorian architects were also swept up in the Egyptomania movement, adding motifs and structural elements into their buildings. Temple Hill Works in Leeds was a nineteenth-century flax mill designed to resemble an ancient Egyptian temple. Still standing in this century and currently the subject of extensive renovation efforts, the mill’s exterior includes Egyptian columns and finer details using symbols and design details familiar to any Victorian Egyptologist.

Prosperous British merchants were so sufficiently fascinated by Egypt that they were willing to fund costly constructions, perhaps eager to associate themselves with notions of the power and authority of the classical world. An obelisk associated with Queen Cleopatra was moved to London and erected on the banks of the River Thames in 1878. Increasing numbers of wealthy Victorians, fascinated by the Egyptian attitude towards death, designed their last resting places to resemble Egyptian monuments.

British Imperialism: Victorian Egyptomania Abroad

Away from Britain, with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the Mediterranean was connected to the Red Sea, joining the Occident to the Orient. The Middle East became a lifeline for the British Empire, making travel to India, a key part of Britain’s worldwide economic influence, easier than ever. Egyptomania had acquired a political dimension that, in the coming decades, would shape how the Victorians viewed their presence in the eastern Mediterranean.

The unofficial occupation of Egypt by the British in 1882 meant that the country and every part of its culture and history began to figure prominently in the minds of politicians and commentators. To the Victorians, it must have seemed that, more than they could ever have imagined, the destinies of Egypt and Britain were intertwined. However, local revolutions would sow fresh seeds of uncertainty in British minds.

In the later decades of the century, writers of popular literature produced dozens of stories telling of vengeful mummies seeking retribution against British interests. In 1892, Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle wrote Lot No 249, a tale of an Englishman using a revived mummy to murder his enemies. And in Pharos The Egyptian (1899), author Guy Boothby created a narrative of social revenge whereby the hero battles a plot to release a deadly poison in England, killing millions. By the last decade of the century, Egypt had become a source of fantasies of social disorder on British soil.

The Legacy of Victorian Egyptomania

Years later, in the 1920s, the seeds of Egyptomania planted by the Victorians would reap a rich harvest when Howard Carter discovered the tomb of the Egyptian king Tutankhamen. This discovery captured the imagination of the world, triggering an explosion of interest even more powerful than the one which had swept 19th-century Britain. The Victorians had established an obsession that continued into the next century. Their legacy was an obsession with the beauty, history, and death found in ancient Egypt. From this intoxicating cocktail, the century’s newest art form, cinema, fed the insatiable desire for fantasies of ancient Egypt.