After World War II, France tried to reclaim its colonial territories in Southeast Asia. Despite American military aid, France was forced to give up its colony of Vietnam. Unable to agree on a national government, the nation was divided in half, with communists moving north and anti-communists moving south. A national election would re-unify the nation under a single governing system…but it never occurred. Instead, the United States became embroiled in a lengthy war to prevent communism from overtaking South Vietnam. Between 1964’s Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, the Vietnam War became increasingly controversial and changed American politics. The war’s aftermath still affects our political system and culture today.

Setting the Stage: Collapse of French Indochina

After Japan was defeated at the end of World War II in 1945, France regained its colonies in Southeast Asia. French Indochina, however, wanted independence. As a growing anti-colonial movement swept Africa and Asia, France fought to maintain control of Vietnam, including with US military aid. This decision was allegedly based on the American Cold War policy of containment, which meant preventing the expansion of communism (or containing it to pre-existing locations). A prevalent fear was that the anti-colonial movement would lead to the expansion of communism as the Soviet Union and Red China offered aid to newly-independent states.

Aided by support from the Soviet Union and Red China, the Viet Minh rebels gained increasing ground against the French. In 1954, they won a decisive victory at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, outnumbering 15,000 French troops with some 50,000 fighters. France pulled out of its former colonies in Asia, leaving the United States concerned about inability to counter communist expansion. The Geneva Accords of 1954 split Vietnam into two states: North Vietnam would be reserved for those who supported a communist government, and South Vietnam would be reserved for those who opposed communism.

Setting the Stage: Developing Vietnam War (1954-64)

The division of Vietnam into two separate states was intended to be temporary. Similar to the Korean Peninsula less than a decade earlier, a diplomatic solution was supposed to reunify the nation peacefully under a single government. An election was supposed to be held in July 1956 to determine Vietnam’s reunified government. South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem and his United States ally decided to cancel the election because they feared that communists might win. This violated the Geneva Accords and enraged the communists who had migrated to North Vietnam.

Beginning in 1957, these communists began returning to South Vietnam as part of an insurgency. The Viet Minh, now called the Viet Cong, were soon aided by the government of North Vietnam. Weapons and supplies began to flow from the Soviet Union and China as well, prompting the United States to drastically increase its own military support for South Vietnam. Under the new US president John F. Kennedy, a staunch anti-communist, the US increased its aid to include military advisors by mid-1961. Within a year and a half, these “advisors” numbered some 16,000.

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

In early August 1964, a US Navy destroyer was allegedly attacked by North Vietnamese gunboats in the Gulf of Tonkin. President Lyndon B. Johnson quickly asked Congress for additional power to conduct the ongoing conflict in Vietnam, which was granted with the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7. With this new authority, Johnson was able to drastically expand US military presence in South Vietnam. He and his administration believed that only by strengthening American military presence could South Vietnam be “held” against communist expansion.

Politically, Johnson was allegedly motivated to intensify the war due to a fear of being seen as the president who “lost” Vietnam to communism. This was likely influenced by Republican criticism of former president Harry S. Truman as having “lost China” in 1949. Notorious anti-communist Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) took advantage of the Red Scare to attack Truman as being a “fuzzy-minded liberal” for refusing to confront communism. Seeking to avoid similar criticism, Johnson aggressively expanded America’s role in Vietnam to project strength.

Escalating War in Vietnam

In March 1965, Johnson initiated Operation Rolling Thunder to try and bomb the communist government of North Vietnam into submission. The US also sought to increase the role of its allies in the conflict, especially Australia and New Zealand. However, unlike the Korean War more than a decade earlier, there was less international support. Since the war had not begun with an organized invasion of South Vietnam, and the US was seen as complicit in the violation of the Geneva Accords of 1954, few Western nations felt the desire to violate the relative peace with the Soviet Union. Thus, the US had to escalate the war with its own troops.

Also in March 1965, the US began controversial “search and destroy” missions to root out communist Viet Cong guerrillas in South Vietnam. By the end of 1965, almost 190,000 US troops were in Vietnam, compared to only 16,000 military advisors just two years prior. In 1966, the US continued to expand its involvement, hoping to provoke the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) into a decisive battle. Despite some 385,000 American soldiers in Vietnam by the end of 1966, both the US military and the Army of the Republic of [South] Vietnam (ARVN) had scored relatively few large-scale victories against communist combatants.

A New Type of Combat: Guerrilla Warfare

The reason for the few noteworthy victories against either the NVA or the Viet Cong was a relatively new type of combat for Americans to encounter: guerrilla warfare. Also known as irregular warfare, guerrilla warfare features ambushes, booby traps, and rapid strikes by small forces against larger, less mobile forces. Despite a massive advantage in armor, artillery, airpower, and overall equipment, the US military struggled to utilize these advantages in jungle terrain against guerrilla fighters who traveled fast, light, knew the area, and had the support of many locals. American forces were often frustrated by the Viet Cong’s ability to choose when, where, and how to strike.

Thus began a war of evolving tactics to try to catch and defeat communist guerrillas. The helicopter became a powerful tool of the US military, as it could insert and extract troops quickly. A desire to counter fast-moving guerrillas also influenced the growth of special forces who were highly skilled and trained in launching and countering ambushes. These teams were also highly desired for their ability to quietly cross borders into Laos and Cambodia, which was technically against the legal scope of the conflict, to intercept communist fighters and supplies. Although the end of the Vietnam War wound down many special operations groups, the practice swiftly re-emerged after the Iran Hostage Crisis. Politically, the relative successes of helicopters and special forces teams led to increased funding for these military tools in the 1980s and beyond.

The Tet Offensive and Aftermath

For years, the White House had been proclaiming the conflict to be almost over, with a victory against communist forces in Vietnam right around the metaphorical corner. In November 1967, General William Westmoreland, the US commander in Vietnam, famously declared that the end of the war was in sight. However, despite Westmoreland’s proclamation that the North Vietnamese war effort was on the verge of collapse, the NVA and Viet Cong launched a major offensive in January 1968 across South Vietnam. The Tet Offensive was quickly defeated by the US military and ARVN but drastically eroded American support for the Vietnam War.

The surprising surge of offensive combat from an enemy supposedly on the verge of defeat shook the American public. Television news was a catalyst for growing public opposition to the war. For the first time, Americans were seeing the horrors of war in real-time, which contrasted sharply with the positive reports being issued by the Johnson administration. Many citizens lost trust in the White House and felt that they had been misled about progress in the war. Seeing the conditions of combat, including injuries and deaths, soured many viewers on patriotic notions of the war against communism.

Anti-War Protests

Anti-war sentiment surged after the Tet Offensive, with more and more Americans considering the Vietnam War unwinnable. Opposition to the war had grown steadily as the conflict escalated, with the first nationwide protest occurring in October 1967. Young people, especially college students, were also opposed to the draft, or conscription. As a sign of protest, people would burn their draft cards. College students were deferred from the draft, leading to a surge in college enrollment during the Vietnam War. Protest music became a popular subgenre among many young people, with popular songs of the late 1960s and early 1970s criticizing the Vietnam War and associated actions.

The anti-war and anti-draft protests were so common that they created a general counterculture movement that merged with existing other social movements, such as the Civil Rights Movement. Many civil rights advocates criticized the Vietnam War and the draft on the grounds that the war was mostly fought by poor and minority men. By 1967, even civil rights leaders who had largely supported President Lyndon Johnson, such as Martin Luther King, Jr., were speaking out against the war. They blamed the escalation of the war for diverting vital funds for social welfare programs and preventing the federal government from focusing on necessary reforms to improve the lives of minorities, especially in the South.

1968: Law-and-Order & an October Surprise

1968 was considered one of the most tumultuous years in US history, especially since the American Civil War (1861-65). The ongoing Vietnam War, especially after the Tet Offensive, had led Democratic president Lyndon Johnson to decide against running for a second full term. As a result, the Democrats held a competitive presidential primary campaign, during which Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-MA), brother of former president John F. Kennedy, was assassinated in June. This tragedy came only two months after the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., putting the whole nation on edge. In August, a huge riot enveloped Chicago during the Democratic National Convention, resulting in televised police brutality.

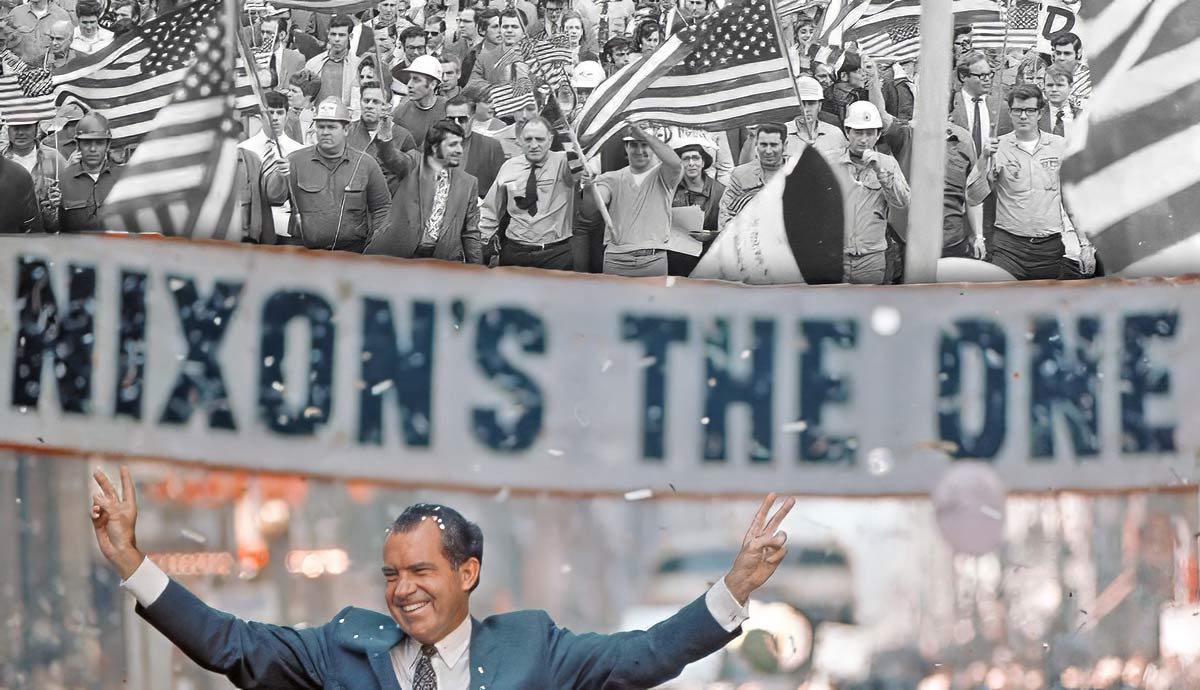

Many Americans had grown weary of the Vietnam War and waves of related protests. Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon, who had served as vice president under Dwight D. Eisenhower during the 1950s, successfully ran on a law and order platform. That fall, during a tight general election contest between Nixon and Democratic presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey, rumors emerged that Johnson’s Democratic administration was going to announce a peace deal with North Vietnam. This “October Surprise” would likely give Democrats the election victory and salvage Johnson’s eroded reputation. Instead, former vice president Nixon allegedly used his connections to sabotage the peace talks and keep the US in the war. Since 1968, “October Surprise” has been part of the political lexicon for an announcement close to election day in early November that has the power to substantially shift public opinion.

Vietnam War Under Nixon: Silent Majority and Vietnamization

Richard Nixon won the presidency in 1968 by appealing to middle- and upper-class Americans’ desire for law and order. Like his predecessor, Nixon continued the Vietnam War. He tried to reduce protests by appealing to America’s supposed “Silent Majority” of conservatives and moderates, arguing that America could only win the war if it appeared unified. The North Vietnamese, Nixon reasoned, would only agree to a truce if it felt the United States was steadfast in continuing the war.

Linked with his Silent Majority speech in November 1969, Nixon also introduced the doctrine of Vietnamization. This policy involved reducing US ground involvement in Vietnam while increasing air power, eventually transferring more ground combat responsibilities to South Vietnam’s ARVN. However, this policy was largely unsuccessful. In April 1970, Nixon expanded the war into Cambodia, which only further invigorated the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. This expansion of the war led to a massive protest at Kent State University, and on May 4, several students were shot by members of the Ohio National Guard. The Kent State Massacre was a major turning point in the national conversation about the war, with a major consensus now agreeing that the Vietnam War should be ended quickly.

1973: End of War and Two Major Reforms

By 1972, having consistently reduced the number of US troops in South Vietnam since taking office, President Nixon wanted out of the war. He was up for re-election in November and was pursuing diplomatic efforts with both China and the Soviet Union. Peace talks between the United States and North Vietnam were held in Paris, and on October 22, shortly before election day, Nixon suspended all bombing north of the twentieth parallel (the border between North and South Vietnam). Despite a brief breakdown in talks after Nixon handily won re-election in November, the Paris Peace Accords concluded with a peace deal on January 27, 1973. The Vietnam War, at least for the United States, was over.

The end of the Vietnam War swiftly led to two major political reforms: the end of the draft and a reversal of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that gave the president virtually unlimited war-making power. The War Powers Resolution of 1973 – passed over Nixon’s veto – required the president to get congressional approval within 60 days to use US forces abroad. The president would have to return all US troops home within 30 days if Congress did not grant either a declaration of war or Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). However, to this day, Congress has never refused to grant an AUMF to a president. Today, the US remains an all-volunteer force and has yet to seriously consider reinstatement of the draft.

1973-82: Era of Foreign Policy Malaise

The end of American involvement in the Vietnam War heavily contributed to a period of political malaise in the United States. Coupled with the growing Watergate Scandal, the failure of the United States to secure a victory in Vietnam led many Americans to distrust the honesty and competency of the federal government. Two years after US troops left Vietnam, North Vietnam won the war by seizing South Vietnam’s capital city of Saigon. The fall of Saigon in April 1975 was a humiliation of American foreign policy and made many citizens question the wisdom of future foreign military interventions.

Between 1973 and 1982, influenced by the unsatisfactory end of the Vietnam War, the US undertook no large-scale military interventions. Under hawkish Republican president Ronald Reagan, the US renewed military interventions in 1982. That August, the US began a peacekeeping mission in Lebanon as part of a multinational force after a 1981 Israeli invasion. However, not until 1983 did the US once again engage in offensive actions against a foreign adversary with Operation Urgent Fury. In October 1983, the Caribbean island of Grenada was stormed by Army Rangers and other special forces groups to neutralize a radical and violent communist government. This action was highly controversial and brought about much violence in its own right but signaled that the United States had “healed” from its post-Vietnam foreign policy malaise.

Post-War Political Effects: Patriotism vs Draft-Dodging

The aftermath of the Vietnam War played out in American politics for decades, especially in regard to foreign policy and the personal background of political candidates. For candidates who were of military service age during the Vietnam War, their service status became fodder for political debate. Some, such as US Senator John McCain (R-AZ), were renowned for their status as war heroes. McCain, a naval aviator who was likely the most famous Vietnam War veteran due to his several years as a prisoner-of-war (POW) in North Vietnam’s infamous Hanoi Hilton, was a popular politician who eventually became the 2008 Republican presidential nominee.

Several other politicians, ranging from Democratic president Bill Clinton to Republican president George W. Bush to Republican president Donald Trump, had their Vietnam-era choices scrutinized. Democratic vice president and 2000 presidential nominee Al Gore faced scrutiny over his Vietnam War service as an Army journalist, especially in contrast with his congressman father’s opposition to the war. Republican vice president Dick Cheney, widely known as a defense hawk beginning in the 1980s and allegedly encouraged president George W. Bush to invade Iraq in 2003, was criticized for actively seeking draft deferments during Vietnam. The need for high numbers of US troops during the Vietnam War led to scrutiny of young men’s decisions to serve or not, prompting controversial questions about personal courage, political beliefs, and moral convictions.