Vija Celmins is a Latvian American visual artist. She first became known in the 1960s for her Photorealistic paintings of war scenes. By the start of the 1970s, however, Celmins mostly abandoned this subject in favor of natural imagery, more frequently printed or rendered in graphite and charcoal than painted. It is this second body of work, which she has continuously pursued for the last 50 years, which has significant implications regarding the relationship between traditional art and photography.

The Context Of Vija Celmins’ Work

In traditional artistic mediums (painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, etc) there is a necessary human content. When working with these mediums, the object is constructed with a great deal of human involvement; the mixing and application of paint to a substrate or the shaping of clay around an armature are done by hand. For much of art history, this fact was unworthy of notice, as this manner of making was the only one. Not just for art, but for all things. These conditions were suspended in the 19th century, both broadly by the industrial revolution, and in art specifically by the invention of photography.

The photograph varied most significantly from the traditional art objects in that it was not made, but merely mediated by a human. Were two different people to press the shutter of a camera positioned in the same way, existing in the same conditions, the resulting photographs would be indistinguishable. Following the invention of this alternative form, ‘madeness’ as a characteristic of traditional art became an apparent subject of interest. Artistic movements from the mid 19th century forward increasingly focused on this as a distinguishing factor, harnessing its meaningful application to justify the continued practice of traditional art.

The Embodiment Of Image

Photography, also, is inherently imagistic; the process inherently references an actual view of the world, albeit translated by monocular vision onto a sheet, but an actual view nonetheless. This sort of representation is surely common in traditional art as well, but there is, at the same time, a necessary amount of invention. A greater loss or reconstitution of information is inevitable in an entirely manual process. Especially in a post-photography world, traditional art requires that the viewer is aware of both the imagistic qualities of an artwork and the madness and material reality of that artwork as an object.

For photography, the embodiment of the image is basically regarded as a perfunctory action. This was also, largely, the case for traditional art prior to photography; as the most efficient and pragmatic form of image-making, it did not need to justify itself by any other means. At present, however, traditional art regards the process of embodiment as not only meaningful but the entire point of making a piece of traditional art.

The physical fact of the photograph itself is essentially a contentless enterprise and thus more easily ignored in favor of the image printed on it. In a piece of traditional art, however, the object itself is a record of its own making – rich with a variety of variously expressive markings, imperfections, and irregularities. So then, the recreation of photographic imagery in traditional art is tricky. There is an inherent contradiction between these two mediums as regards this interest in ‘madeness.’

The Philosophy Of Photorealism

The American Photorealists of the 1960’s and 70’s (including such visual artists as Robert Bechtle, Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, and Audrey Flack) attempted to resolve this formal contention; These artists sought to temper the sense of ‘madeness’, and therefore humanity and emotion, inherent to paintings. These qualities, which defined painting as a separate and worthwhile entity in a post-photography world, had become canonized and aestheticized in preceding artistic movements such as Abstract Expressionism.

The photorealists were interested in discovering what modern painting looked like when these qualities were repressed. For the Photorealists, this was accomplished, in theory, by the deployment of photographic imagery within painting, as photography was thought to be mechanical and unexpressive. The human element of content and form is always strictly limited in early American Photorealism. The goal of the movement can be summarized as an attempt to balance photographic images within painting such that the content and form of the piece cancel each other to the point of utter vacuity.

The Hidden Contradiction Of Photorealism

Another Photorealist visual artist, although distinct for many stylistic reasons, Vija Celmins demonstrates how traditional art and photography are not precisely opposed such that they cancel the effects of each other in this way. Rather, the nature of the disagreement between these two mediums is that embodiment in the crafted object serves painting but interferes with photography. For modern painting, the fact of the object is the very reason for painting, where photography only takes on a physical form out of necessity and hopes to otherwise avoid acknowledgment of its body. So, when a painting is populated with photographic imagery, the result is not a comfortable, neutral state, but instead a fraught and conflicted object.

A Contemporary Visual Artist And Her New Photorealism

Since the late 1960s, Latvian-American, contemporary, visual artist Vija Celmins, has demonstrated this conflict through her own evolution of the Photorealist style. Celmins pursues the same blunting of human presence as these other, aforementioned photorealists. However, her pictures reveal the fault in believing that traditional art and photography could be neatly joined together. Instead, Celmins’ work is made vital by how close she comes to bridging traditional art and photography, that is, negotiating their contradictions into a unified whole, only to reveal an endless and unresolvable cycle of negation between the two. Vija Celmins’ work not only acknowledges this necessary instability in any combination of traditional art with photographic imagery but is in fact empowered by the tension this instability creates.

The Human In Photorealism

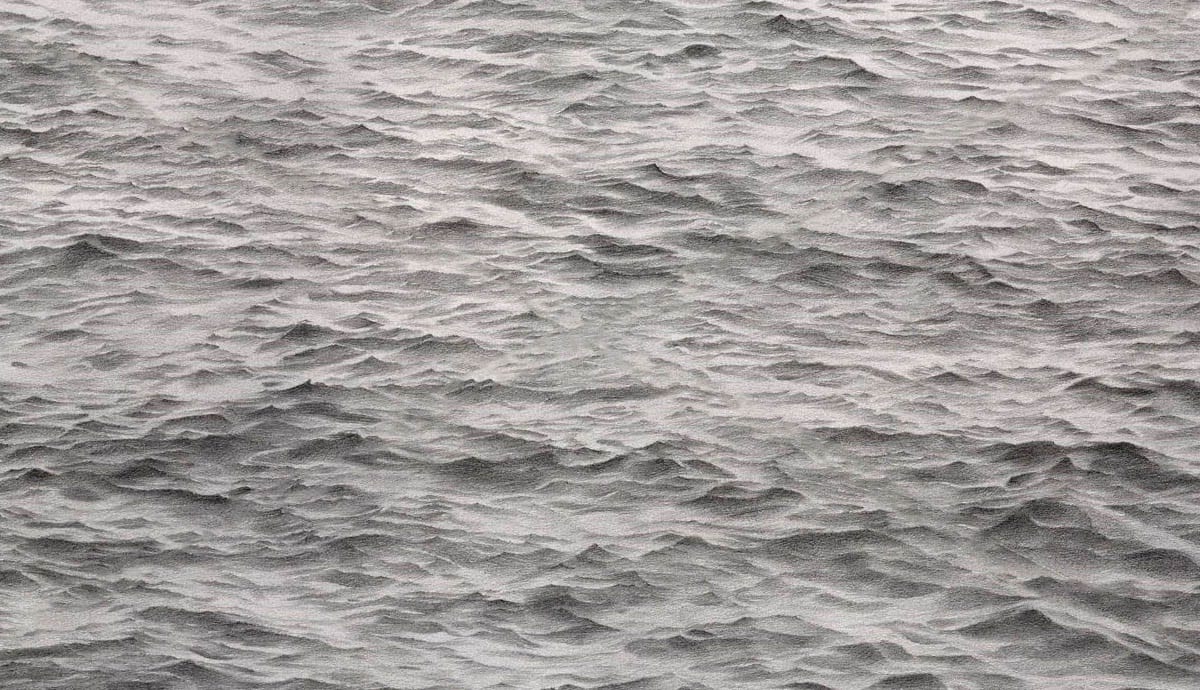

Vija Celmins, in her mature work, tends to prefer natural subjects: the ocean, sky, and desert, are common motifs. Her choice to divorce the content of her work from anything human entirely is common in Photorealism. Many of the artists working in this style made ironic use of banal imagery such as cars, diners, and suburban landscapes as a means of further suppressing the expressive features of painting; all of these subjects are themselves mechanically produced commodities, lacking the individual characteristics of the handcrafted.

What is notable in Vija Celmins’ subject matter is that it bears no trace of the human whatsoever. She is not content merely denying the presence of the human body, but also prohibits any product of mankind from appearing. She, more than any other photorealist is obsessed with the extraction of human traces. What this extreme position counterintuitively reveals is the indispensable, human truth of her chosen mediums.

A curious effect occurs when imagery devoid of humanity both in literal content and by the exacting, unaffected specificity of photography is translated into traditional art forms; the viewer becomes hyper-aware of the few remaining signifiers of this traditional medium and its base materials. The grain of the canvas or paper, or the impact left on this surface from the drag of her pencil, or the subtle layering of paint resulting in an uneven finish. As soon as one understands that the piece is not merely a photograph these flourishes stick in the mind. These barest traces of humanity peeking through an otherwise undifferentiated and impartial surface cannot be unseen. By placing them in such painfully near proximity, Vija Celmins demonstrates the distance between photography and traditional art cannot be closed. The two are like oil and water. Celmins mixes photography and traditional art with ferocity, but they always threaten to separate.

The Limitations Of Art

This effect can be observed in Vija Celmins’ portrayals of the night sky. Stars, the tiny flecks of light, sit against a field of either stark black or graduated grays. The incomprehensible vastness of space between each of these stars, and from those stars to the viewer, is collapsed into the surface of a piece of paper covered in charcoal or stained with ink. Despite the care and exactness with which these views of the sky are recreated, the material reality never disappears; Celmins has tasked the oil, graphite, charcoal, ink, paper, canvas, and panel from which she derives these pieces with something insurmountable. To work in these mediums, especially in a modern context, is to call specific attention to that choice. Whereas, in the source photographs, their physical bodies are understood more as side effects, unimportant and best ignored. For the photograph, ‘madeness’ disappears, but for the painting, drawing, or print, ‘madeness’ is their purpose. No matter her skill or diligence in accomplishing the transformation of these materials they remain strikingly evident, never disappearing into an ocean or sky.

Vija Celmins’ Denial Of Presence

Beyond fundamental incompatibility, Vija Celmins’ “Web” series illustrates how compromising traditional art with photographic images actively detracts from the ability to represent. The subject of these works, spider webs, are themselves so slight and scarcely present in actuality, that mere representation can come much closer than usual to convincing emulation. Often, in representational, traditional art, painting especially, the physicality of the material is used to help suggest the presence of the things being depicted. In the works of Lucian Freud for example, the generously applied paint becomes analogous to the flesh of his nude models. Even this modest suggestion of actual form and presence is surrendered in Celmins’ work in the pursuit of a smooth and photographic surface. Compounding this is the lowliness of a spider web; not even the little presence it might actually possess is truthfully communicated.

The Photorealism of Vija Celmins is engaging because it refutes the style itself. Throughout her works, depicting natural forces and spaces, the visual artist is always verging on abstraction. This abstraction is born immediately in the pictorial isolation and reconfiguration of these subjects. Sitting with these works, however, reveals a higher level of abstraction: the awareness and purposeful presence of objecthood, which defines traditional art from photography. By the fraught relationship of these two, brought together in her studied Photorealism, Celmins brings into focus the impotence of the artists’ materials; not only the inability for these traditional mediums to act as photography does but also their ability to act as themselves.