According to the Norse sagas, a man named Naddoður was returning home to Norway from the Faroe Islands when his ship sailed off course. The ship was off by around 300 miles and brought Naddoður to Viking Iceland. Iceland was not Iceland in the ninth century. It was the largest uninhabited island on earth (except for the presence of a handful of Irish monks). The open island gave Naddoður big news to take back to Norway. Sweden soon received similar news. A man called Garðar Svavarsson circumnavigated the island, and modestly named it Garðarshólm, settled for the winter, then returned home to Sweden with news of a wide-open island.

How Was Viking Iceland Settled?

The sagas credit a man named Flóki Vilgerðarson with the first attempted settlement of Iceland. He followed a raven to the island but struggled in the new land and returned to Norway after less than a year. He allegedly named the island Iceland, which has lasted much longer than his time there.

Around 874 CE, Hallveig Fróðadóttir and her husband Ingólfur Arnarson arrived in Iceland. They settled vast swaths of land and according to the sagas were the first permanent settlers of Iceland. Although Norse sagas are full of promising detail and exciting adventure, they were written centuries after the events they depict and are considered unreliable resources by many. Archaeology offers another avenue for exploring the Viking settlement of Iceland, one that does not always contradict the sagas.

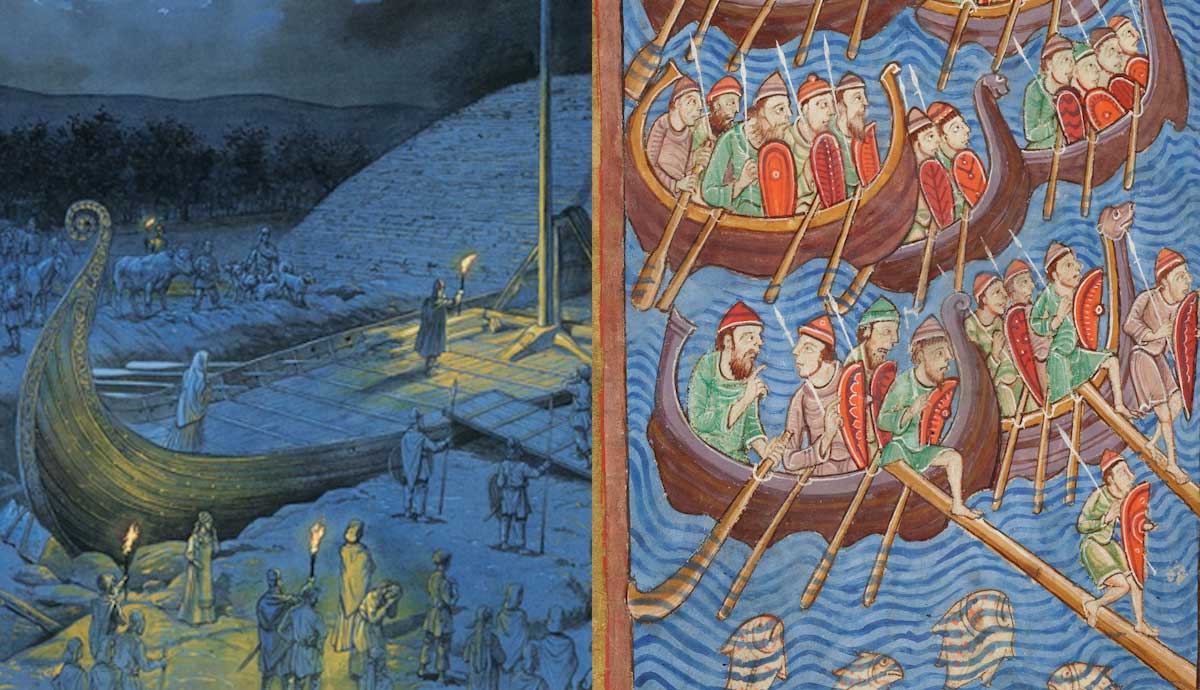

Ships

The sagas highlight ships and sailing as pivotal elements of the settlement of Iceland. While ships were key to the Viking settlement of the island, they have been slow to emerge from the archaeological record. Less than twenty Viking Age ships have been excavated in Iceland, but other evidence of this important nautical heritage has been uncovered. In Iceland’s Mosfell Valley, archaeologists have discovered stone ship settings. Stone ship settings are outlines of ships made from stone. Frequently, they mark graves. They have been found in numerous places in Viking Age Scandinavia but are less common in Iceland.

In 2017, archaeologists made a series of successive ship discoveries in Eyjafjörður fjord in North Iceland. Three boat burials emerged from the earth. One ship contained the grave of a Viking Age chieftain, his sword, and his dog. While the ships that allowed for the discovery, settlement, and sustenance of Viking Age Iceland have emerged slowly in Iceland, recent discoveries raise hopes that more ships are to come.

Settlements

The sagas indicate that it took the Vikings a while to settle Iceland. It was an inhospitable new home, but the Vikings proved up for the challenge. The Book of Settlements enumerates the land acquisitions and transactions of around 400 principal settlers. Archaeology reveals that the Vikings settled along the coast and in lowland areas that were habitable.

Viking settlements consisted of farms with turf structures and expanses of arable land. According to Norse accounts, some twenty-two settlers made their homes in Skagafjörður. In Skagafjörður, archaeologists found evidence of around 17-20 Viking Age farmsteads. Viking Age settlements continue to be excavated across Iceland, revealing broad consistencies with the settlement patterns described in the sagas. The archaeological evidence provides additional insights into how the Vikings built their homes and what their world looked like; details not always available in the sagas.

Longhouses

Perhaps the most iconic structure to emerge from the excavation of Viking Age settlements is the longhouse. Archaeologists have found several longhouses in Iceland. In 2001, archaeologists found the remains of a Viking settlement under the streets of Reykjavik. The earliest portions of the settlement dated to around 871 CE. A tenth-century CE longhouse was also uncovered.

In 2020, archaeologists announced the discovery of a new longhouse in eastern Iceland. The longhouse lay beneath the remains of another late ninth-century CE longhouse. Predating the top longhouse, the new longhouse threw a wrench in the established narrative of Viking settlement of Iceland. Archaeologists suspected that the new longhouse represented a seasonal settlement used by Norse fishers and trappers.

The Norse sagas attest to the establishment of temporary settlements in Iceland by several Scandinavian figures as well as permanent settlements. The archaeological record continues to illuminate when and how the Vikings settled into their Icelandic longhouses often aligning with the saga narratives.

People

The sagas suggest that the colonists of Iceland were Norwegian and British refugees of the Norwegian King Harald Fairhair’s taxation and colonization schemes. Although thousands of Vikings settled the island, only a few hundred graves have been excavated. Archaeologists used strontium isotope analysis to assess 90 burials of early settlers. This analysis revealed that some individuals had migrated from areas other than Iceland during the earliest phases of Icelandic colonization.

These people came from several places, potentially confirming the diversity of the settlers depicted in the sagas. In Ketilsstaðir, a Viking Age woman was found buried with brooches, beads, textile fragments, a touchstone, a knife handle, a spindle whorl, and a piece of chalcedony. Studies of the textiles buried with this woman support the interpretation that she was born in the British Isles and migrated to Iceland. Sagas also suggest that feuds between the settlers were resolved through violence.

In the Mosfell Valley, archaeologists found the body of one man who had been violently bludgeoned in the head with an axe or a sword sometime in the late tenth or early eleventh century CE. Certainly, not every Viking faced such a brutal demise in Iceland but archaeology continues to point to some accuracy in the Norse sagas.

Artifacts

Iceland’s environment presented numerous challenges to the Viking settlers. When the Norse arrived, the only land mammal on the island was the arctic fox. Archaeology reveals that the Vikings had to import animals for their survival. Excavations have revealed bones of cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, horses, chickens, dogs, and cats. Some of these domesticated animals would have been kept for their by-products, others as pets or food. Not all animals were for eating. Archaeologists have discovered horse remains in several hundred Viking Age graves, and suggest that horses were sacrificed in ritualistic burials.

Excavations of a tenth-century CE house in Reykjavik recovered beads, nails, a spindle whorl, and a piece of a glass vessel around the home’s hearth. These artifacts suggested that the hearth was a hub of activity during the Viking Age and pointed to cultural connections with the material culture of medieval Scandinavia where beads and spindle whorls are commonly found at Viking Age sites. Although Iceland presented the Viking settlers with unique challenges, many artifacts point to the continuation of identities, styles, and lifeways established in Viking Age Scandinavia.

Trade

The sagas and archaeological record agree that many Vikings settled in Iceland. The sagas imply their break from mainland Scandinavia was not permanent. Walrus tusks, jaw bones, and baculum from Viking Age contexts show that the Vikings concentrated great effort on walrus hunting and ivory extraction. According to the sagas, walrus items from Iceland were traded with Norway. Initial archaeological investigations seem to support this idea. Sagas also detail Icelandic imports of cloth from England, Norway, Ireland, and Constantinople. Textiles recovered from archaeological excavations indicate that the textiles were traded across the Norwegian Sea between Iceland, Norway, and the British Isles.

The End of Iceland’s Viking Age

All good things must come to an end. The Viking Age gave way to the medieval period. Icelanders accepted Christianity as the island’s one and only religion. Norway conquered the island and Iceland became a Norwegian province in the thirteenth century CE, bringing an end to the traditional authority of chieftains. From genetics to cultural monuments, the Vikings have cast a long shadow through their settlement of Iceland. Together the sagas and archaeology continue to shed light on their pioneering world.